What Ian Livingstone did next

He's done Fighting Fantasy, Games Workshop and Tomb Raider. Now, it's time to teach.

"My own education was pretty average."

Ian Livingstone CBE has done it all: tabletop games, game books and of course video games. He co-founded Games Workshop, co-wrote Fighting Fantasy and co-launched Tomb Raider. He's been all over the world, wearing in each city a different hat. He's met with success, failure, ups and downs. But now, at an age when some might have craved a comfy retirement, he's coming home, to where it all began, to start the next chapter in the adventure book of his life.

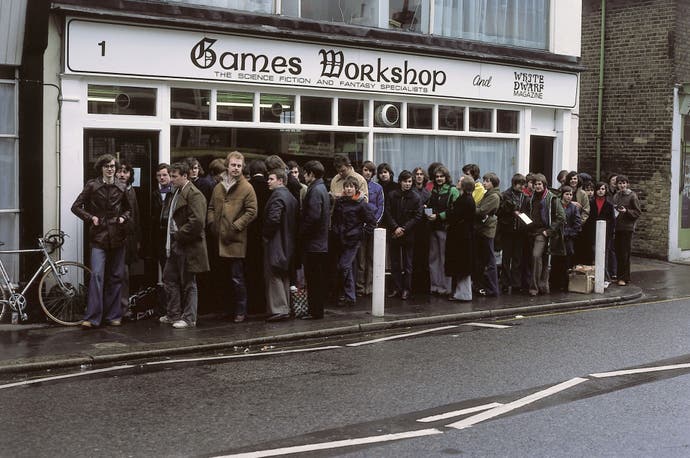

In 1978 Ian Livingstone opened the first Games Workshop store in Hammersmith, west London. Without the push of a Facebook page or a trending hashtag, people came. People queued. Kids queued round the street, their imaginations excitedly awaiting a spark.

Now, in 2014, Ian Livingstone hopes once again that kids will queue in Hammersmith, their imaginations excitedly awaiting a spark. But this time he's not opening a shop. He's opening a school.

The Livingstone Foundation is trying to gain permission from the government to build a public school in Hammersmith that would specialise in teaching 800 students aged 11-18 the wonderfully appropriate STEAM: Science, Technology, Engineering, Art and Mathematics. The idea emerged as Livingstone, then Life President of Eidos, launched the Next Gen skills campaign, which successfully lobbied government to add computer science to the national curriculum. If the Livingstone School is approved, it should open next year and begin teaching kids not just how to use technology, but how to create with it.

"My own education was pretty average," he tells me. We're at the central London offices of Playmob, one of the many game-related companies Livingstone works with. With a smile he mentions he left Altrincham Grammar School for Boys in Manchester with just one A-level - grade E - and decided against university. I get the impression Livingstone has remained frustrated with the education system ever since.

Livingstone wants to teach computer science to the next generation in a different way. He wants to move away from what he calls the "Victoria broadcast model of talk and chalk" to "actual learning". This, he says, is essential to the UK's economy, digital future and, hopefully, video game industry. "We're educating children for jobs that don't even exist today," he says.

This month Livingstone submits the gargantuan, one hundred page application form to the Department for Education he hopes will convince the powers that be to give the Hammersmith school the green light. The Foundation has hired experts to advise on each area of the document, from curriculum to budgets, and it's pushing hard to get the parents of 120 kids to sign a petition to say the school would be their first choice to boost its chances. Livingstone will know the good or bad news by March. If it's good news, the school will open its doors in September 2015.

Livingstone's desire to teach is driven in part by his own, "pretty average" education, but also his frustration at how ICT (information and communications technology) has been taught for so many years. "ICT was nothing more than a strange hybrid of office skills," he says. "Kids were learning how to use technology but had no idea how to make their own technology. They could play Angry Birds but had no idea how to make Angry Birds."

His point is that learning how to use the likes of Microsoft Word, PowerPoint and Excel, as I did in school, is not enough in the modern age. "Question one: who invented the world wide web?" Livingstone asks. "Frankly, I couldn't give a damn. That's a quiz night question which I can ask Google, and within a millisecond I'll get the answer. That's not knowledge. That's learning facts. We don't want that in computer science. Show me a code and I can give you a job, however."

Livingstone, clearly, has a burning desire to see this through. "I'm a stubborn northerner who when told it's not going to happen makes him even more determined," he says.

"Question one: who invented the world wide web? Frankly, I couldn't give a damn."

On 30th September 2013 Livingstone quit his job as Life President of publisher Square Enix to go it alone, ending a near 20 year association with Eidos, the company behind Tomb Raider, Hitman, Deus Ex, Championship Manager and many more games.

The split seemed amicable, according to the statement the Japanese publisher issued when it announced the news. But it came amid sweeping changes at the company. After Square Enix reported sales of Crystal Dynamic's Tomb Raider, IO Interactive's Hitman: Absolution and United Front Games' Sleeping Dogs had failed to meet sales expectations - for many unreasonable sales expectations - the company embarked upon a restructure that saw a number of layoffs, game cancellations and the resignation of boss Yoichi Wada. The emphasis now is less on big budget blockbusters and more on digital, and making the most of its impressive portfolio of intellectual property with cheaper and quicker to develop titles.

And so I wonder whether Livingstone was one of the casualties of Square Enix's new way, or perhaps he quit in protest at the changes that were being made. When I quiz him on the subject he displays all the diplomacy I'd expect of an industry veteran with experience of dealing with politicians.

"I had to cut the umbilical cord at some point," he says. "I was 17 years at Games Workshop, 20 years at Eidos and Square Enix. We'd been bought five years ago by Square Enix. This was always going to happen at some point. It was just a question of when. I think the time was right."

Livingstone says it "wasn't appropriate" to continue to be life president of Eidos as he was "effectively a satellite", travelling the world, giving talks, promoting the industry, lobbying government and planning to open a school.

Again, everyone seems like the best of friends. "I've still got my office there," he says, smiling. "I've still got my email address. I'm still associated with the company. We're still on good terms."

"The time was right for both of us," Livingstone stresses. "I was pretty much unemployable as a person, coming from Games Workshop, writing books, starting off at Eidos. I've always been one of those people who's not very good at not doing stuff I don't agree with particularly. It's not that I don't agree with anything Square Enix is doing. It's just that the time was right for me to do my own thing once again."

"I've still got my office there. I've still got my email address. I'm still associated with the company. We're still on good terms."

Livingstone left Eidos with some of the biggest and respected names in games - he calls the portfolio "fantastic" - and is convinced Square Enix can manage the transition to the new way so many of its competitors have found troublesome. He compares the company to a super tanker "that's been headed in the same direction for so many years", that, all of a sudden, must change direction. "I'm sure they'll get it right."

Then, some advice: "They shouldn't apply the old criteria of P&Ls relating to games that cost $30 million to make. They've got to be able to say yes or no quickly, and just get things going.

"I think they'll be absolutely fine. They've got a lot of cash. And they've got some of the best IP in the world. They just have to reinvent themselves, which they are doing - faster than some publishers, I might add.

"Japanese culture means they take their time. They don't move as quickly as some western publishers. They see what other people are doing and usually take best practice to go to the next stage. So I wouldn't say they're doing things wrong. They're not moving as quickly as some because that's the Japanese way of doing things."

Did Square Enix ruin Eidos? Did it ruin Hitman? Tomb Raider and all the rest? It's a suggestion that, every so often, pops up on the internet as the debate about the company rages on. Livingstone, again, is diplomatic.

"It could have been quite easy for Square Enix to say, yes, we've bought some fantastic IP, let's close down all the western operations and move production of those IPs to Japan, and then served the world franchises that were first aimed at Asian cultures and second western cultures. But they didn't do that. They recognised it wasn't just about IP. It was about development talent, and Eidos had some fantastic development talent in terms of IO Interactive, who created Hitman, Eidos Montreal with Deus Ex, and Crystal Dynamics with Tomb Raider.

"They allowed those studios to focus and be the best they could be, giving them additional time and capital to realise their ambitions. From that point of view, Square has been very supportive."

Free from Square Enix and his job as life president of Eidos, Livingstone's new working week looks like this: around two days are spent on The Livingstone Foundation, another day spent giving talks at home and abroad (he's just been to Bilbao to give a talk to the International Olympic Committee on how to use games to promote health and rehabilitation), a day looking after indies he's invested in or companies he's involved with, another day sitting on various boards - Livingstone is trustee of GamesAid, vice chair of UKIE, chair of the Computer Games Skills Council and he sits on the Creative Industries Council. Oh, and he's just been appointed a visiting professor of the University of London to talk about education, and he's been added to the Computerspielemuseum Berlin Wall of Fame, where his picture sits next to that of Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak.

If that wasn't enough, he's also trying to write another Fighting Fantasy book (2012's Blood of the Zombies went down well) and, get this, he's designing a couple of games, which he can't talk about yet. And there's a screenplay for Deathtrap Dungeon doing the rounds. "Whether anything will happen is another matter, but it's pretty good, I must say."

Not much going on then. "I'm just a young kid having fun," he says, smirking. "I'm never going to retire. There's no chance. Because if I retire I'll just play games, so I might as well be involved in making them.

"I've seen a couple of my friends retire, and their brains have gone a bit mushy. Games really keeps your mind active. They're a good thing. If you think what's happening when you're playing a game - and this is what I'm saying to politicians - whether you're problem solving, puzzle solving, choice and consequence, intuitive learning, creativity, community, social skills, trial and error, teamwork, risk taking, these are life skills."

"I did get to meet Angelina Jolie a couple of times on the set at Pinewood. I'm still recovering from that."

When I ask Livingstone the rather predictable question, what's his proudest achievement, he pauses, deep in thought. He declines to say - it would be like asking him which of his four children he loves the most. The parallel is apt: he has four children in real life, and four children in his business life: Games Workshop, Fighting Fantasy, Eidos and now the Livingstone Foundation.

Let's narrow it down to video games, then. "Launching Tomb Raider," he answers, his eyes glistening as memories of the mid-90s, the fun and the games, the best of times, are rekindled. "We had a lot of fun and a lot of big moments and extraordinary success.

"It was quite a ride."

Why Tomb Raider, I wonder, as if it wasn't obvious.

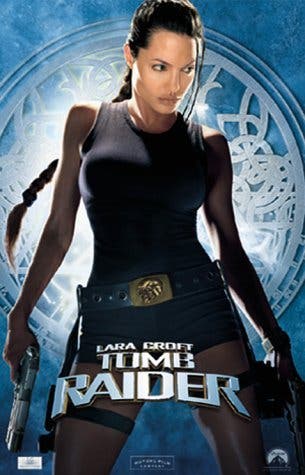

"She's one of the most famous icons in the world, Lara Croft, but she went beyond the game industry, largely because of the two movies," Livingstone says.

"I remember when we were negotiating with Paramount we made a veto over their cast and their scripts. We didn't want them taking Tomb Raider into a place we didn't want it to go. When they said we'd like Angelina Jolie to play the role of Lara Croft we said that's absolutely fine with us. I did get to meet her a couple of times on the set at Pinewood.

"I'm still recovering from that."

Launching Tomb Raider comes out on top of an illustrious video game pile. Livingstone fondly remembers signing a young Warren Spector, who he was familiar with from the 70s pen and paper role-playing scene, to create the first Deus Ex. "I knew that was going to be an incredible franchise because he was the master of that genre of role-playing."

He remembers the day Hitman came through Eidos' green light committee, as it was back then. "We loved the idea of the game," he says. "It really had that Ronseal title: Hitman. You knew exactly what you were going to be doing. You were a hired assassin and that was it. You didn't need to know any more rules. They had a great team with some fantastic people. That was an easy decision."

So good was Hitman that Eidos bought its developer, IO Interactive. "Hitman 2 was the big one for us. It broke new ground in merging stealth with action in an immersive environment. The missions were thrilling." Livingstone wasn't involved in the Hitman movie as he was in the Tomb Raider films, but, "I thought it was pretty good."

Any regrets? "We all make mistakes, and making mistakes is part of learning, isn't it? So I don't have any regrets."

Perhaps regrets is the wrong word, then.

"I've made a few mistakes along the way, but don't we all? I'm sure I could have done a lot of things better, but it's best not to worry about that. Just get on with the next thing."

"I've made a few mistakes along the way, but don't we all? I'm sure I could have done a lot of things better, but it's best not to worry about that. Just get on with the next thing."

Despite all the roaring successes, the next thing could be Livingstone's most rewarding - and important - challenge yet. If the Hammersmith school is a success, he wants to use it as a blueprint for the launch of more schools outside of London. "Clearly I want this to be nationwide."

For an elder statesman, I find Livingstone surprisingly clued up about how kids view the world these days. "Theirs is a connected world," he ponders. "They run their lives through their smartphones and social media. They share everything, even their private details. We have to work on that basis to allow them to learn."

Livingstone hopes his school will help kids "hack their way in an informal sense to creativity", with peer to peer learning that talks on their terms at their level at their rate. "There's a lot more deeper learning going on than just trying to listen to some guy or girl boring them to death with random facts," he says.

If it all works, the Livingstone School could help inspire the next generation of video game developers. Livingstone's education was "pretty average", he says. If he has his way, for hundreds of kids, theirs will be anything but.