Walking in a giant's footsteps: a father and son story

Through art and Guild Wars, a Romanian family finds the American Dream.

Did you end up following in your parents' footsteps? I wanted to be my own man but here I am, writing just like my dad did (only he won a BAFTA - I doubt I'll ever do that). Horia Dociu is around the same age as me and - with his constant effing and blinding - he talks a lot like me. He's got a dad a bit like mine n' all: something of a tough act to follow. And Dociu's following in the footsteps of a real giant. His dad is none other than Daniel Dociu.

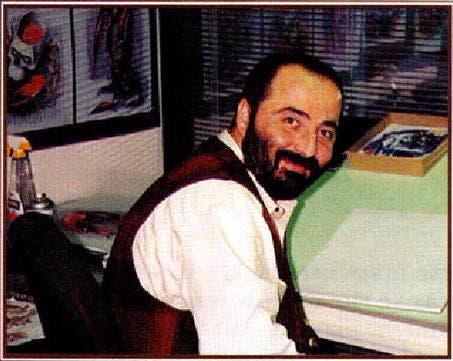

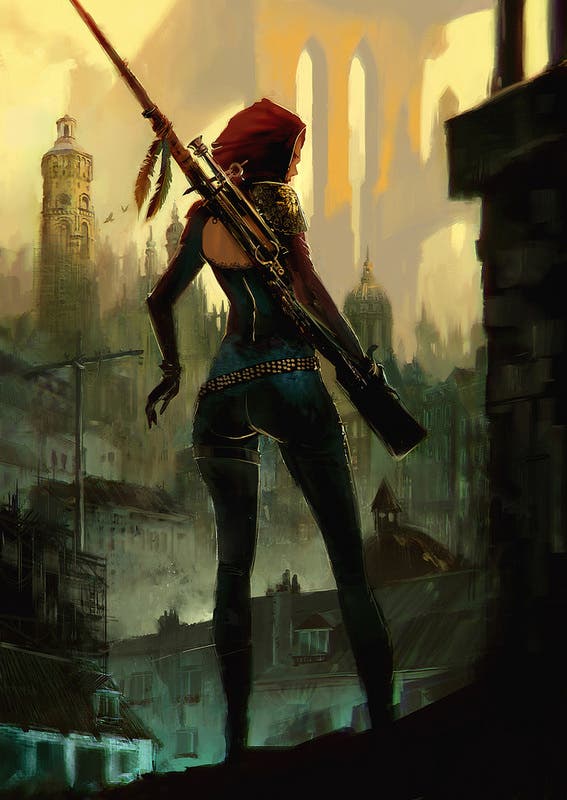

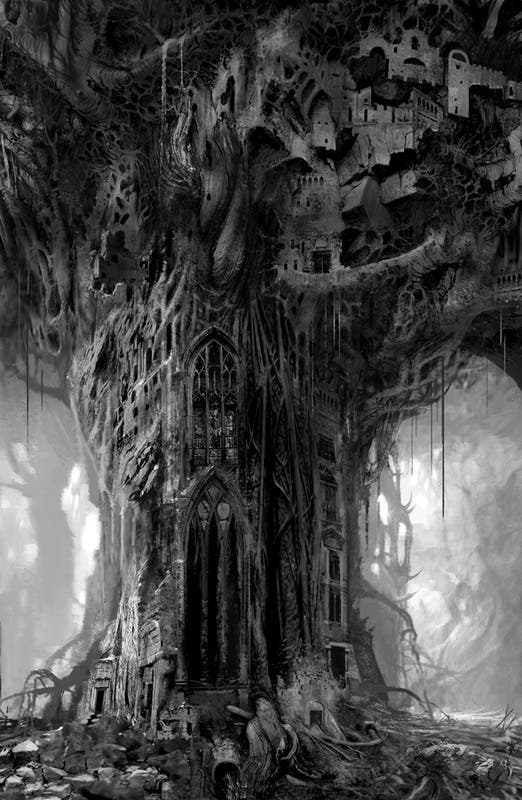

In the world of video game art, Daniel Dociu reigns supreme, with countless awards from organisations such as Into the Pixel, Spectrum and Lurzer's Archive. He was given the Grand Master Career Achievement award by Exposé, putting him in such hallowed company as illustrator and Alien designer HR Giger.

Moreover, Daniel Dociu revolutionised Guild Wars. When he joined ArenaNet in 2003, the game looked like crap. It had no style and no identity. He established the art culture there, gave Guild Wars its painterly and ornate look. He's the reason art leads the agenda there today, the reason art adorns the walls - and much of it is his. He's the reason an army of 120 artists - 120 artists! - call ArenaNet home. He even rose to become overseer of all NCSoft West art.

But earlier this year Daniel Dociu walked away, and into his impossibly long shadow a successor stepped. A successor who looks at him as wide-eyed today as he did all those years ago in Romania, when him and his family had to move away. This is the story of a family chasing that endangered thing called the American Dream.

"I was about seven years old and so it was all really vivid," Horia Dociu tells me over the phone. "They packed up fishing poles and made like they were going on vacation in Greece - it took seven years to get a visa to do even that. Then they stayed there and said, 'Hey, political asylum!' They left us with our grandparents for a year. It tore my parents up inside.

"It was very intense for me because I wasn't supposed to tell people where they were or what they were doing because of the secret police, the Securitate, so that stuff was: 'Oh I don't know,' 'Oh they're on vacation.' It wasn't like the kids at school were going to turn me in but it was like, 'Oh I'm keeping a secret,' and, 'When am I going to see them again?'"

Romania in the 1980s was a Communist police state led by the oppressive and paranoid Nicolae Ceau?escu, and enforced by his brutal Securitate secret police. It was a country on the brink of revolution; years of extreme austerity had pushed the people to breaking point. It wasn't safe. What the Docius did, they did for their two children.

"When we got back together in Greece... My dad remembers it as having a shitty apartment on the basement floor with no windows and just having to walk everywhere. And I was like, 'Are you kidding me?!' When we went to Greece it was fucking Disneyland.

"There was fruit juice and there were toys and there was a little black and white TV. Everything just seemed so magical," Horia says, "and we were jumping on the bed having a wonderful time."

In 1990, after years of saving - and one year after the Romanian Revolution begun - the Docius had enough money to move to America. Quickly the parents, who met studying at the Fine Arts Academy in Cluj, put their skills to use. "My dad would take on any art-related job, making signs for a pizza place or whatever he could do. He ended up at this toy company here, just outside of Seattle, that was making novelties: fake vomit, Treasure Trolls - back in the '90s those were a hit. He was drawing the doctor troll or the Gorbachev troll - and all sorts of action figures that never came out."

Daniel's portfolio had been filled with industrial design up until then. "Now he was drawing these gross monsters and funny characters, and he met this young artist named Dev Madan," Horia recalls, "and Dev was doing a poster for Final Fantasy 3 at Squaresoft, and was like, 'Bro! You've got to get into games - fuck this toy stuff! Games is where it's at. You could make 40,000 a year!'"

Daniel couldn't believe his ears. "40,000 a year?" he said. "Oh my god!" So he grabbed the newspaper, found Squaresoft's address in Redmond, Washington, and applied.

Horia and his sister couldn't have chosen their Dad a better job - you can't work in games and not let your kids play them, after all. The two children pitched in and bough a SNES, and at first it was only allowed on weekends until things slowly loosened up. "Growing up we had every console," Horia says. Their dad didn't necessarily play them all - he was often bewildered by the buttons and errant cameras - but he observed enough to know what he was dealing with, while remaining far enough away he could think outside the box. "He would come up with something that was so bizarre and trippy that, at all these companies, people would go, 'How the fuck are we going to do that? There's no way it's going to work.'"

Daniel making video games also made his workplace the coolest in the world for 11-year-old Horia to visit. "He'd be crunching on Secret of Evermore [SNES, 1995] and I would get to go putz around the office and play the new Final Fantasy while it was still in a board and not a cart yet," he says. "They were these really chocolate-factory kind of special weekends here and there. It blew my mind. I saw that they had a jar of candy and I was like, 'Are those free? You can just have a candy whenever you want?!'"

Daniel would nod and smile, and even arranged a small testing role for Horia on Secret of Evermore which, according to Horia, was the last old-school role-playing game made in the West, and he received a free copy for all his hard work. "And I'd go, 'Dad, do you ever think we'll get to work together someday?'"

Art had rubbed off on Horia, as parents' passions tend to. "They never pushed us to be doctors, they never even pushed us towards becoming artists. But whatever you do," they told Horia and his sister, "try, try, try! Do your best."

When Horia drew, they were there, offering advice like teachers on demand, and so, with encouragement and guidance, his skill and enthusiasm increased. He wanted to pursue it professionally, so off to the DigiPen Institute of Technology he went.

Horia's dream of working with his dad came true when he was just 17 years old, at now-closed SOCOM developer Zipper, where they'd collaborate on SOCOM: US Navy SEALs for PS2, and Crimson Skies PC. But the job that really stood out on young Horia's portfolio was making Half-Life 2 at Valve.

"It was freaky at the time, those guys were so ahead of the game. I was used to a Nintendo 64 game I had been working on, and PlayStation 2, where you're literally pushing pixels, little squares. Then I get to the kind of textures they do and it's like photo manipulation - it looks real. I'm like, 'Wow - am I going to keep up?!'

"To be honest I learned a few hard lessons," he says. "There were a few weeks where I turned in rubbish work and I got a talking to, and it really gave me a sharp kick in the ass about the quality bar that those guys maintain."

Daniel had been working at EA but had somehow still found a way to get his face in Half-Life 2, as dour Father Grigori, Ravenholm protector and guide. "Steam was just some guys on the first floor in a room trying to figure something out. It was a different company," Horia says.

Horia wouldn't see Half-Life 2 released because in 2003 his dad tempted him somewhere else, to an office very slowly sinking into a Seattle swamp - a place he would stay for a very long time. "I was downtown at Valve and he was five minutes away at ArenaNet and he says, 'Come check it out.' I looked at the game online before I went and it was... not pretty," he says, referring to the original Guild Wars.

When he got there, though, his mind changed. "Wow, it's really cool," he thought. "It feels a little more home-brewed than Valve. This feels a little more like you could get dirty and make some moves," and so, convinced, he joined his dad for the ride. It was not to be an easy one.

"When I first started on Guild Wars he was really - and I don't know if I should talk about this but it's funny to me now! - he was very concerned about the feeling of nepotism not being something that people paid attention to, so we speak Romanian and he would just whisper, 'I will fucking fire you myself if this thing isn't done by Friday.'

"And it's in a cheeky, joking way, but he was extremely hard about making sure everything I checked into the game was tops, was really clean and looked good."

Horia was instilled with a tough work ethic from his parents. It was something they felt, as Romanians living in America, they had to do. "There was this notion we had to work a little bit harder, we had to be a little better to stand out. My mum would get made fun of, called names because she had a thicker accent, and she's very smart, very wonderful to talk to, but there's this accent and people would say, 'Go back to wherever you're from.'

"There was always this thing of 'be better, do better'."

Daniel wouldn't let Horia off. "Come on! That's not really pushing - here's pushing!" he'd say, painting over his work. "I'll show him," Horia would tell himself, knuckling down. But again Daniel would wander over and say, "Huh, not a lot of colour contrast in this..." and Horia would internally explode.

"Every single time I thought I had it he would have one more, two more things for me, and often it would end up in him saying, 'Go back to the drawing board.' An expression he uses is, pardon my French, 'You trying to pixel-fuck this thing isn't going to make it better - you've got to start fresh.'"

"No but I already did this and that..." Horia would protest.

"Start again," Daniel would insist.

"That's when I would get a little peeved, like, 'Oh come on! You're just being extra hard on me.' But I would do it, and every single time when I was finished I would go, 'Fuck, he's right, he's right.'"

That hard work saw Horia rise from being an environment and concept artist to being ArenaNet's cinematics director in 2007. By the time he left the studio in 2011, he had been an integral part of every single Guild Wars release, including the in development Guild Wars 2. Horia left ArenaNet because, as good as the internal progression path had been, there was nowhere left to go - nowhere except art director, and that was his dad's role, "And obviously my dad's The Man."

He poked around and discovered that Dev Madan, coincidentally the guy who'd encouraged Daniel into video games all those years ago, was leaving his art director post at Sucker Punch, so Horia applied there. Directing art on major PS4 exclusive inFamous: Second Son, and standalone expansion inFamous: First Light, was a much needed step up, a necessary jump in the deep end. "The way I consider it was I grew up at ArenaNet and then I went to grad school at Sucker Punch," he says. "And now I'm back for my doctorate." Horia rejoined ArenaNet in 2016 to work alongside his dad once more, only this time as an art director.

If he painted a stern picture of his dad before, he tells me, he didn't mean to. "He looks a little intimidating with the beard and everything - that's why they chose him for Father Grigori, in that he looks kind of scary - but he's just the nicest guy. The truth is he's really charming, very friendly.

"We're kind of best buddies. When he was working here he'd call me down to his desk three, four times a day. He'd be working on a new illustration and he'd say 'come look at it', and obviously he's the master - I've got some years to catch up to where he's at. That's humbling and also teaches me a lot."

That was Daniel's way, to gently but firmly coax the best out of people. "He's not just telling you to do something different but showing you how your thing could be better, and if you don't give enough of a fuck to make your thing better, you just don't care about your craft."

One thing Daniel treasured particularly was spotting good ideas that came out of nowhere, from an intern or a happy accident, for example. To Daniel, a good idea was a good idea regardless. "'Let's elevate this,'" he would say. "My pops is all about pushing that forward."

Daniel would also encourage emotion in his artists. "His big advice was 'cry every day'. He says if you're not emotionally vulnerable as an artist to the point where watching a nice commercial, or movie short, or hearing a good story, brings you to tears, then you're not really letting yourself go - you're not relaxing enough. You're too uptight to be doing good art."

It all tallies with the impression Daniel left on me five years ago, when I saw behind the curtains of ArenaNet and Guild Wars 2. He was a deeply thoughtful but open and friendly person, with a kind of paternal affection for his team. He was also aware he was closing in on the end of his career so had to make every year count. "At my age I don't feel like I have the luxury of wasting a development cycle," he told me, which goes a long way explaining why, five years later, after the release of Guild Wars 2 and expansion Heart of Thorns, Daniel Dociu decided to leave ArenaNet, a place he fundamentally helped shape over the course of 13 years.

"The reason he went isn't because he doesn't like ArenaNet or that he was unhappy," Horia says. "He was frank with everybody and said, 'Look, I'm going to retire in a few years. Unless they invent some pill that reverses old age, I have to retire.' He wants a new challenge. He's built this awesome culture at this company and he could have stayed here for another 10 years, but he wanted, for himself, to get out there, get feisty, try something new."

Daniel Dociu now works at Amazon overseeing all of their game projects - an initiative we expect something significant from but don't know much about just yet. His departure left ArenaNet with a chasm to fill. ArenaNet is 400 people and the art team alone is 120 - it's a huge operation. There were senior leads who could do the job and there was the option of bringing someone in from the outside, but would they know the team, would they understand the game and the culture? Horia didn't think anyone 'off the street' would. But he did because he helped build it, so the 35-year-old bit his lip and said, "Heck yeah I'll go for it."

"I put in a good word for you," Daniel would later say when Horia told him the good news. "I think you are the best fit for the job. But I also told them, 'I'm not going to work here any more - you guys have to live with this decision.'"

"I think he was pleasantly surprised," Horia says, "as was I."

Horia stepped into his dad's shoes in February this year, and to shake off the nerves he gave himself a pep talk. "I'm not Daniel, I'm never going to be Daniel," he told himself. "At best I'm competing with Daniel when he was 35, not now when he's 60. There's no way you can be Daniel but there's no way anyone else can be Daniel, so whoever takes this role is going to be their own person and is going to have their own way to work with the team and collaborate with management, and have their own artistic vision. So go, just do it, day by day.

"Do I have my own opinion? Heck yes. Are there things that I love? Heck yes. But they're not naturally going to come out. My personal lens is going to be that 'yay or nay' when I see a piece of work, and I'm going to have to work through my coaching. If people like it, great. If they don't, I don't know, fire me!"

If 10 years ago you'd told him he'd be the guy running desk to desk, department to department but not drawing much, he wouldn't believe you, yet if he's learned anything it is to go where his talents take him. Maybe he isn't destined to win awards but to coach and manage instead. Regardless, he won't stop trying - Daniel taught him that. Daniel didn't start really winning awards until he was over 50.

"He was a good draftsman but the kind of out-of-this-world, insane and beautiful artwork came very recently. He didn't start doing that until within the last decade. That's something that I'm taking with me," Horia says. "Don't ever slow down or say 'it's too late' or anything like that. You can be too old to be an Olympic figure skater, you can be too old to be a gymnast, but you can not be too old to be a fantastic artist, and whatever shape that takes, he's setting a good example by making his last professional gig something that's a challenge to him and that he's a little bit afraid of."

Whether one day Horia will outshine his dad, or leave his own recognisable mark on Guild Wars, or win awards, is not what it's about. "Doing art to be famous or make a mark or anything like that, it's missing the point. You've got to do stuff you love and that you care about, and that feels like you're expressing yourself. If you get famous, if you make a mark, if you make a splash: hooray - but that's a side effect."

Plus, this is his dad we're talking about, not some contemporary rival. To Horia, Daniel was, is and always will be, his hero, and he's still there, and is still a huge part of Horia's life.

"The truth is twice a week I'm on the phone with him for work going, 'Hey blah blah blah blah how do we do this thing?!' He's there and he's giving tips and he's giving me pep talks, saying, 'Fuck no you don't take that answer! You go on and you do this and you ask that.' It's a little bit like running along with a bicycle and he's let go but he's still running alongside - it feels very nice.

"Getting to work with them and follow in their footsteps feels like, and this is going to sound cheesy, but it's that American dream they were going after," Horia says. "Once in a while I'll go have dinner at their house and we'll all just look around and go, 'fuck, man, we're so lucky.'"