Why we need more developers like Zoe Quinn

To reach their full potential, games need to stop empowering the player and embrace the raw and personal.

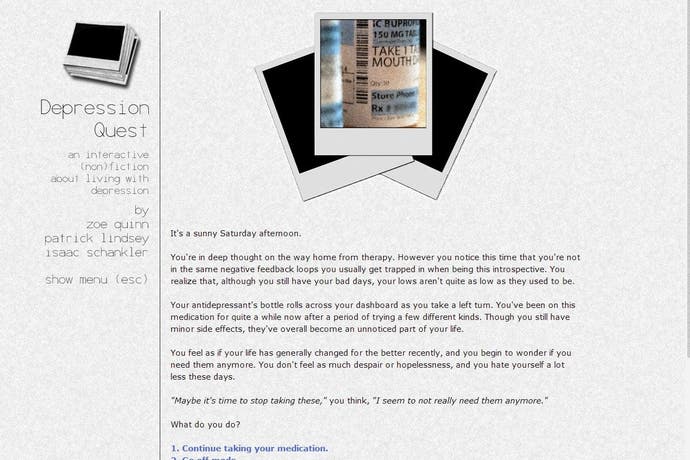

I've been replaying Depression Quest recently. The sudden passing of Robin Williams put depression on the agenda in a big way, and the game is free on Steam as a result, and developer Zoe Quinn has found herself the subject of scrutiny elsewhere, too. It's obscured some of what she achieved with her game, which is well worth returning to.

Depression Quest is an important game, and one that's brought into focus a nagging thought that has been buzzing around the back of my mind for months, like a wasp forever out of the corner of your eye. Namely, that I wished game developers were more selfish. That's the wrong word to use - too emotive, too negative - but the sentiment feels right. Game design, particularly at the commercial end of the scale, has become so player focussed, so obsessed with ensuring that every game appeals to everybody, and that everybody can understand everything intuitively, that it risks becoming faceless and infantile.

We're going to skirt dangerously close to the "games as art" debate here, but it's something we need to grapple with. Games shouldn't be afraid of that three-letter word, just as they shouldn't be fixated on it. Games are a creative medium, made by creative people. They are, by nature, capable of being art. They're just not very good art, most of the time.

And the reason for that, I suspect, is this user-first way of thinking. I'm not advocating that games should resort to incomprehensible control schemes or refuse to tell players what they need to do, just that art - truly great art - rarely comes about by thinking of what other people want. It comes from someone having something - an idea, a feeling, an experience - that they are compelled to externalise and share.

In other media, that's pretty much taken for granted. Nobody thinks it odd that an actor would mine their own life for emotional truth, that a writer would pour themselves into their prose or that a musician would write lyrics from the heart. The whole thing with art is that you can catch reflections of the artist through it, and over time and pieces of work see as much - or as little - as they need to share.

Does that happen in games? Sometimes. Rarely. Think of the most famous game designers, then ask yourself what you can tell about them from their work. Peter Molyneux has made many "god games". There's clearly something there that fascinates him. Could you actually say what that is, though? Taken as a body of work, what do Populous, Powermonger, Black & White and Godus have to say about omnipotence, or worship, or faith?

Kojima comes closer than most to delivering AAA games with subtext and meaning, even if they're often buried under mercurial monologues and scatological slapstick. David Cage has interesting ideas, but keeps getting hung up on the idea of games as movies, and ends up spiralling off into pulp silliness by the end. Apart from those examples, looking over the gaming landscape reveals lots of mechanical polish, lots of flowcharted user experiences, but precious little humanity in all its complex, contradictory, messy glory.

That's what makes a game like Depression Quest so vital. It's not just that it's beautifully written and absorbing, but that it's personal. Painfully so. Each scenario is rich in detail, from judgemental parents to uncomprehending acquaintances, and the way certain options are closed off to you as your mood dips - still visible but unclickable in their red strikethrough text - is a simple yet ingenious way of illustrating how a deep dark low can feel. You know what you should do, but you can't do it. In that moment of interface frustration, you get an echo of what that feeling must be like when depression engulfs your whole life. It takes a familiar gameplay mechanic and uses it to illuminate something with real meaning and weight.

If you have experience of depression, it will ring horribly true. If you haven't, it offers a small but immersive glimpse into what it can be like. While countless other people could have made a game about depression, this one could only have come from Zoe Quinn. It's clearly something that Quinn was compelled to make, to put out there, to share, and in doing so, exorcise it, however briefly.

Too often, the emotional content (and context) in games is ghettoised in cutscenes or voiceovers, where we learn that Character X is sad or happy or hopeful. That's fine and valid, but games will always come second to cinema where that sort of storytelling is concerned. It's really about developers using gameplay itself to make us feel or experience something we otherwise wouldn't have. To let us walk in somebody else's shoes, and maybe not have them be the blood-spattered boots of yet another super soldier. To share something of themselves, be it literal or abstract, beyond making us feel awesome all the time.

I certainly don't expect the industry to ditch Unreal 4 in favour of Twine any time soon - I'd just like to see more unique and individual perspectives like the gruelling but emotionally rewarding journey through Depression Quest, more viewpoints and ideas that don't assume I'm the centre of a fantasy universe where pretty but hollow worlds are created to empower me, and me alone.

Let's have some of the singular spirit of Depression Quest, or dys4ia, That Dragon Cancer and This War of Mine leaking into the wider game design lexicon. Let's have blockbuster games where there's a distinctive individual human voice inside the code with something to say. Developers like Zoe Quinn aren't threatening the norm in big ticket video games, but rather pointing to an interesting, more engaging future for the medium.