Why I love video game credits

Another list feature?

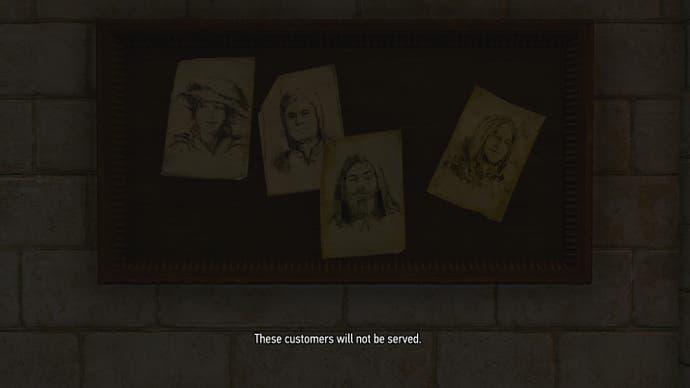

In a wood in the south of The Witcher 3's Toussaint lies a cemetery called Mere-Lachaiselongue. Perhaps you've been there, and perhaps you took the time to read the the inscriptions on its tumbling gravestones. If you did, they might have given you pause. They don't really fit in Toussaint, or, indeed, in White Orchard or anywhere else.

"Martina Lippin'ska. Engineer and pug lover. Solved the most obtuse technical problems in all the duchy with the grace of a ballerina."

"Natalie Mrooz. Duches Ademarta's court sorceress. Granted the wishes of the common folk."

They're strangely specific. They sound like real people. In fact, could these be CD Projekt RED technical QA analyst Martyna Lipińska and administrative specialist Natalia Mróz? As much as they break the fourth wall of this lushly realised land, I love these little nods to the people who made The Witcher 3. (Mind you, having encountered a man with the initials DLC right at the start of this digitally delivered expansion, metafictional jesting is part of The Witcher's MO.) They seem to nod to tales of the people behind a game that's already all about stories.

"Caroline Nyev'eglovska. Believed it was possible to reach a satisfying agreement with anyone. Died while negotiating with a charging fiend."

They also seem to indicate pride in people, and particularly in the kinds of roles which are so usually buried deeply in the infinite scroll of the credits of a modern video game: the QA coordinators, additional engine programmers and Italian localisation editors. While some of the gravestones reference senior sound designers and animation directors, all are equal here in virtual death.

I always watch the credits of video games. I'm not sure why. I tell myself it's for professional insight, to recognise names and note relationships to better understand the industry, but there's something else to it, too. I find them mesmerising, enjoying the sense of finality (despite presumably only having finished whichever game they're from on Medium, not having touched infinite mode or the multiplayer). And thus I watched Uncharted 4's credits, which seem to say much about that that game is. The great majority of the early credits are artists - first the art directors, animation leads, cinematic animators and technical art leads, and then great blocks of names: 44 environment artists, 27 animators, 11 technical artists, 12 lighting artists, 11 character artists. Their numbers overwhelm those of programmers and speak of the burden of work that Naughty Dog bore to create this stupefyingly visual game.

The Witcher 3's credits are far more balanced, a reflection of the blend of disciplines required to create a sprawling world rather than a laser-guided linear adventure. They lead with the studio heads, producers and directors of each area, including those for engine, QA and music, before proceeding through programmers, writers, quest designers and environment and character artists. They're overwhelmingly Polish names, underscoring The Witcher's localised nature, while Uncharted's names are thoroughly multinational.

But good lord, does Uncharted have the numbers, for deeper into its credits, between Naughty Dog and Sony's ranks of territorial marketing managers, lie the names of all the outsourced talent that worked on the game. I counted over 220 artists from companies like China-based Virtuos, Mindwalk Studios and Original Force, and then Sony's own internal resource, VASG Animation, adds a further 50. The richness and detail of the modern video game - including The Witcher 3 - is down to the work of these generally unsung developers, who also contributed to the likes of FIFA 16, Halo 5 and Metal Gear Solid V, as well as films like The Force Awakens and Captain America: Civil War.

Even indie games like Firewatch are product of rather more people than make up their core studios. Campo Santo is just 12 people, but Firewatch's credits lists the help of umbrella company Panic, which provided producers, marketing, QA and other support, and external help came from prop and visual effects artists, character modellers and sound designers, plus Unity's Asset Store community.

I often think about the order in which names appear and wonder how hotly contested was the jostling for positions. Did the game director and senior producer come to actual blows, or just leave it at passive-aggressive Slack reaction emoticons? And what's the story behind those executive producers from the publisher? Every entry is tantalising evidence of the real responsibilities and work that went into making the game. And sometimes we've witnessed those arguments, such as when 100 developers from Team Bondi were left off LA Noire's credits.

On the other hand, you get approaches like those of Insomniac and Valve, where the studio credits are simply an alphabetical list of names without attribution of roles. Marketing head Doug Lombardi has explained that it's down to Valve's peculiar structure, where everyone does a little of this and that and therefore can't neatly be pigeonholed. I can't help but think that it's also a cute show of propaganda for Valve's company culture, and when you break credits down into a list of faceless names, it does rather call into question what credits are for, anyway. They're immediately skipped by the great majority of players, even when some games like Kinect Rush and Sunset Overdrive award achievements for watching their credits (I am throwing a stern glare at Guitar Hero Live for requiring you to watch its credits twice), and others make them great in and of themselves.

Are they some attempt to add some Hollywood pizazz with slow-burn intros and the closure of the end scroll? Maybe, but ask the International Game Developers Association (IGDA), and they'll tell you that individual game developers value them because they can put them on their CVs. In fact, the IGDA has guidelines which say that any person who has contributed to a game for at least five per cent or 30 days of the project's total work days should be credited. And there's the academic element too: since every videogame will continue be studied into the future, it's a point of principle that they should contain metadata about where they came from, weird and patchy as credits actually are.

Scholars might want more information, but for me, the weirder and patchier the better. Every mystery adds another dimension of wonder to a game world. Those production babies, were they born into crunch-forced neglect? The studio dogs and abstract lists of thanks. The alto and baritone choir singers - do they like video games, or was that recording just another job? That's why I love that cemetery in Mere-Lachaiselongue. These fragmentary glimpses into how video games were produced make them come more alive.