Torment: Tides of Numenera review

Planescapism.

Kickstarter-fuelled nostalgia or not, it takes more than a little self-confidence to name your game after one of the smartest, most beloved, most respected RPGs ever made. That's not a percussion heavy soundtrack you're hearing in Not Planescape Torment: Numenera, just the clanking of its giant brass balls. And yet somehow, against the odds, inXile does it proud. To be clear, Planescape remains by far the superior Torment, but Numenera is as close as anyone's gotten to not just recreating what it did, but the experience of discovering it.

Both games have their roots in pen-and-paper universes, though as with Planescape, it actually helps not to know much about the world so that you can learn along with the main character. You're not an immortal amnesiac this time, but rather the 'Last Castoff' - in brief, there's an entity called the Changing God who likes building himself new bodies every decade or so, then just dumping the old one. That's you this time, though like your brothers and sisters, you retain your consciousness, and are a relatively common sight in the world.

It's a fantastic world, too. Numenera is SF rather than fantasy, set on top of eight civilisations' worth of toys and wreckage that range from familiar robots to full-on demonstrations of Clarke's Third Law that any sufficiently advanced technology can be combined with a silly hat to make its user look like a wizard. It's a multicolour world of strange floating doohickies and spinning triangles and particle fountains and ancient clocks the size of buildings, and honestly a real breath of fresh air after the far more traditional settings of recent RPGs like Pillars of Eternity and Tyranny and even The Witcher 3.

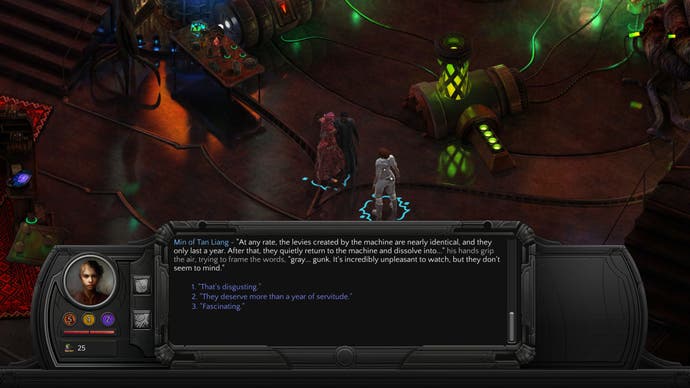

It's not just enjoyable for letting the artists play with the full colour palette, though - it's a great setting for quests and stories. One of my favourites from early on involves the 'Levies'. Like all the best RPG quests, this one is both an assignment and a way of learning about the world in a more active way than just being told the lore. The basic concept is that the first area, Sagus Cliffs, is protected by golem style creatures called Levies, powered by a year of life donated by new citizens. One however has gone horribly wrong and is perpetually in tears. It turns out that its donor was a petty criminal who was planning a big heist that would have ended in tragedy. Instead, after becoming a citizen, he shaped up. However, his Levy remains a product of that year that never happened, complete with all the terrible memories and guilt. Your task is to persuade his creator to gift him a better one.

This approach as much as anything is what Numenera takes from Planescape Torment. There's more overt things, like shout-outs to a past castoff called 'Adahn', villains called the Sorrow that look exactly like the Shadows, and the unnamed main character not usually being able to die, albeit mostly for plot convenience rather than anything really justified in story. However, the interesting parts are invariably the moments it finds more philosophical takes on quests, to wrap the familiar in strange and twisted new imagery, and build a bigger picture of the world through smaller, seemingly isolated nuggets of plot and character.

Where it stumbles, it's typically because very few of these details feel as personal as The Nameless One's slow realisation that he's basically behind every scrap of pain he encounters. The Last Castoff isn't completely disconnected from past actions, obviously, but is a big step away from being personally responsible for anything, in a story that often feels afraid to get truly dark, and whose philosophy leans more towards long speeches and debates than the perfect simplicity of Planescape's central question "What can change the nature of a man?" or Mebbeth's exquisite deconstruction of classic RPG fetch quests.

Again though, we're talking about a stone-cold RPG classic here. Working on the same levels is already more than most even attempt, and falling a bit short is nothing to be ashamed of - even if it's impossible to overlook that 'Tides of Numenera' is the real title here, and 'Torment' less a summary of the plot than a general statement of design intent.

It's also worth noting that a lot of the above is mostly an issue in the first couple of thirds of the game, with the third - a genuinely alien place called the Bloom - finally showing real teeth. I'm glad the whole game's not set there, as I did enjoy the sunlight and lighter touch of the Cliffs, but I would have liked more of its lingering menace and threat to kick in a bit earlier, when the Last Castoff doesn't face a whole lot except socially awkward "Hey, haven't we met?" conversations and hunting for the plot in a maze of side-quests.

Mostly, questing is standard issue fare, with a bit more focus on picking text-based options to get things done, and occasional breaks into full-on interactive fiction when exploring the past. The most dramatic break from the norm is what Numenera calls its 'Crisis' system, and it really is a refreshing way of handling more active encounters and retaining player choice.

The idea is simple. There's almost no combat in the game, and none of it is the usual ambient goons just standing around, or NPCs going from "Hail, friend!" to "WE MUST FIGHT TO THE DEATH!" at the slightest nudge or insult. Action encounters are sparse but complex, initiated only at key story moments and often possible to cut off before even that by using your party's pool of Might, Intellect and Speed points to intimidate or persuade or slink away in silence. When it does, the world shifts to a turn-based system. Instead of just fighting, however, you can still talk, use items, manipulate the battlefield, and more.

The system often works great, as the first battle showcases. Normally it would be a straight-up fight. Instead, you can play with light bridges, intimidate the enemies into fighting poorly or straight up giving up, weaponise the arena with the right skills, or simply surrender, be knocked out, and wake up wherever it was they planned to take you in the first place. The second big one takes the system in more of a stealth direction, using musical devices to distract not-immediately hostile enemies and with failure causing a diplomatic incident between two species, rather than simply dropping you back in for a second attempt.

The further into the game you get though, the less inspired these sequences become. By the end there are far too many characters taking forever to take their damn turns and the initial sequences' complicated, interwoven mechanics have been boiled down to stuff like 'kill everyone or hit that crystal three times. Yes, that one just sitting there in the open.' The final really big fight - surviving until a certain event - was so boring, I put on a movie. While there are options to avoid combat at times, having a non-combat build didn't help me avoid taking shots and knocks on the way to these non-violent solutions.

The later sequences aren't helped by the fact that while, technically, you're supposed to be balancing a limited number of Intellect, Might and Speed points to spend on physical challenges and conversations, with the more you spend increasing your odds of success, Numenera never really puts the screws on. You only spend a few of them per choice, most challenges can be given to any member of the party rather than just the Last Castoff (big exceptions being calling back on previous memories) and it rarely takes many to get an almost guaranteed success. The result is that it's almost never worth gambling instead of just straight-up buying a victory. In addition, not only does a full team have points pouring out of every orifice, there are boosters, and while staying at an inn to recharge them is expensive, it's not so expensive that it's ever actually a problem to do that as needed.

I don't want to be too down on either system though, as both are good ideas and preferable to the bland combat and tedious skill-checks they replace. When the Crisis system works, it feels like a GM is controlling the fight, just as the points system has a few clever subtleties, like combining with individual skills such as Persuasion to distinguish between, say, talking a character down versus shouting them down. That guiding touch isn't always there, though, and the longer the game clicks on, the more it feels like the passing of time itself should probably have been listed as co-designer - its razor hands slicing away the early subtlety in favour of brute-force solutions.

In particular, there's a certain awkwardness to much of the world. It's hard to put a severed finger on exactly what it is, because it's not that Numenera lacks for quests, locations or content. At the same time though, you can't go into many buildings on the map, areas are small and fairly sparsely populated, and much of the content on offer is oddly shared out. Take for instance Sagus Cliffs. For all of its quests, in practice you only need to complete a couple to get to the second hub. That's a full third of the game that you could easily spend ten hours investigating, or almost complete by sheer accident- not least because the lack of combat/difficult skill checks removes any sense of how powerful you currently are or need to be at any given time. Your current level really tells you nothing.

Luckily for Numenera, the audience most likely to enjoy it is also the audience most likely to be tolerant of such mechanical things. The obvious comparison is with Pillars of Eternity, a game rooted in the RPG mechanics of Baldur's Gate et al, and the feel of the old Infinity Engine. Torment however, then and now, is a game built on story and narrative; of seeing promises of over 1.2 million words and going "Hurrah!" instead of emitting the kind of groan that normally involves a regrettable curry washed down with a whole cheesecake. If you're the kind to just click through the text, avoid. That's where most of the fun is.

And in that regard, it's successful. Like its predecessor, Numenera may not have invented its world, but it makes it one you'll want to spend time in. Where other RPGs are still content with a dragon or some apocalyptic end of the world boom, here the stakes are personal, as well as both asking and inviting far more interesting questions than how much fire you can fling from your fingertips. It's a far more welcoming game than the original Torment, though a slower burner as far as the main plot goes, and one that never quite has its predecessor's dark confidence. It is, however, as close as we've had in the last 15 or so years, and certainly doesn't invoke the name in vain.