The story of SWIV

So What, It's Vague.

One of the more curious licensing phenomenons of the 80s was the home-exclusive sequel to an arcade game. Manchester's Ocean Software specialised in the trick, creating follow-ups such as Target: Renegade and Yie-Ar Kung Fu 2. However, as the 90s dawned, a general tightening of licensing laws meant fewer home-exclusive sequels appeared. Instead, inspired by an official arcade conversion hit, one company stretched its remit to a spiritual sequel, creating one of the finest shoot-'em-ups of the era in the process.

Developer-publisher The Sales Curve was formed in 1988 by ex-Telecomsoft employee Jane Cavanagh. "Between '85 and '88, I frequently went to Japan on behalf of Telecomsoft, negotiating the sale of our titles in Japan and purchasing arcade game licences," she remembers. "Even though the industry was in quite an embryonic stage, through my travels to Japan, I became convinced that it would be huge." Cavanagh's belief in the games industry compelled her to leave Telecomsoft and start her own company, The Sales Curve, initially to help others with licence acquisition, product development and distribution. "Within the first year, however, we started developing our own titles and self-publishing."

One of Cavanagh's contacts was a coin-op producer named Tecmo. Tecmo had occupied the second rung of arcade game manufacturers before the popularity of side-scrolling shoot-'em-ups such as R-Type and Gradius thrust its 1988 game, Silkworm, into the limelight. As a result, Silkworm was top of Cavanagh's list of potential arcade games to license. "It was relatively easy as I already had a good relationship with Tecmo - I then just had to assemble the creative and management teams," she says. Under the banner of Random Access, The Sales Curve's team focused on the 16-bit games first.

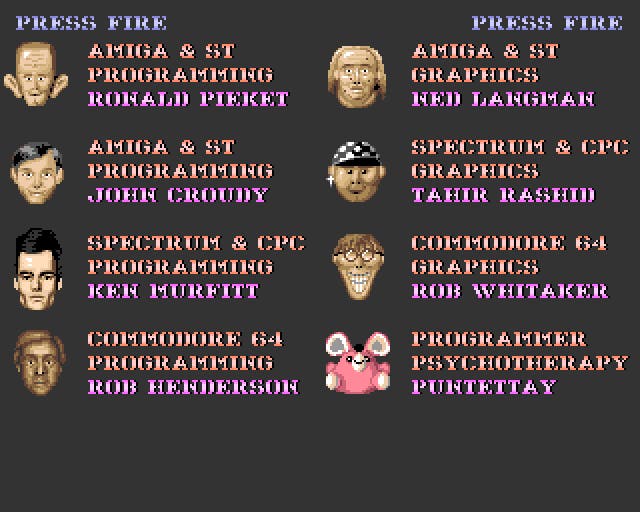

Part of that creative team was programmer Ron Pieket. "Silkworm was a surprise hit," he tells me. "The Sales Curve was a newcomer to the scene, and it really put them on the map." From the Commodore Amiga to Amstrad CPC, Atari ST, Commodore 64 and ZX Spectrum, each version of Silkworm was a critical and commercial hit - a rarity for arcade conversions back in the 80s, with at least one port almost always turning out to be a dud. Cashing in on Silkworm's success became a priority for Cavanagh, but there was just one slight problem: Tecmo hadn't actually created a sequel to the arcade game itself. So if The Sales Curve was going ahead with another Silkworm game, they couldn't call it Silkworm 2 and were understandably reluctant to pay Tecmo just for that honour. "But it meant we had complete artistic freedom," notes Pieket, "and as we were fans of vertically-scrolling games, that decision was easily made."

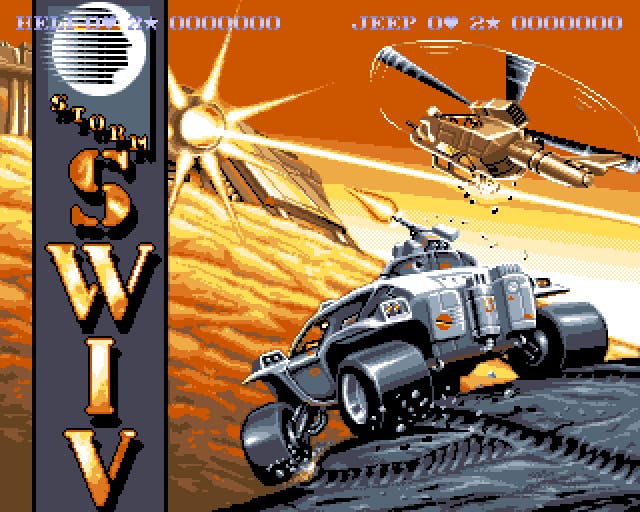

Partnering with Pieket on the 16-bit games was artist Ned Langman. "We all loved Silkworm, and it had been described by some critics as better than the arcade original. Jane was so pleased that she wanted to use the same team to work on something new. We were also fans of top-down vertical scrollers such as Xenon and Battle Squadron, so we wanted to do something like that." In honour of its inspiration, the working title for The Sales Curve's next game became Silkworm 2. "We all searched for an original name, and various ideas fed into it becoming SWIV," continues Langman. "It is still a mystery as to what it exactly means!"

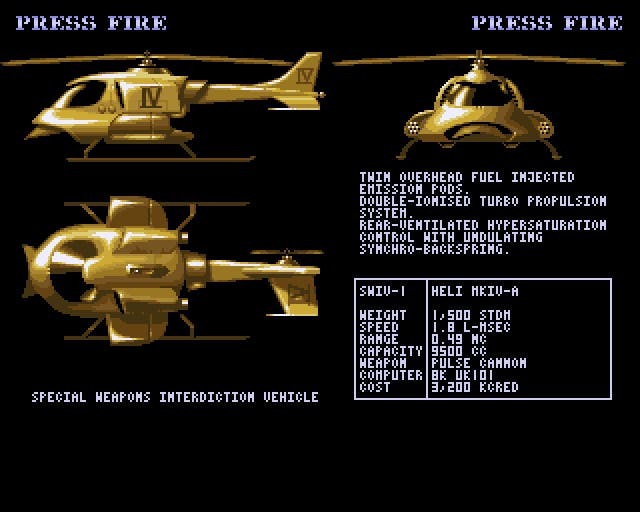

SWIV's name, a charming acronym of nebulous origins, became a focus of its advertising campaign, frequently discussed in the pages of games magazines. According to the game's intro, it stands for the slightly clumsy Special Weapons Interdiction Vehicles. "It was a spiritual sequel to Silkworm, and we thought it was so far advanced that we should call it Silkworm 4 - having skipped two and three!" laughs Cavanagh. Other interpretations included Silkworm In Vertical and Sold Without Interference of Virgins - a tongue-in-cheek reference to The Sales Curve's erstwhile distributor, Virgin.

But there had to be a decent game behind the hype and name. "The design was a collaboration between Ned and myself," remembers Pieket. "And the first thing I did was develop the level editor." Pieket and his colleagues were keen to give SWIV a special look and create a shoot-'em-up that felt fresh. "Whereas practically all the games back then used tile-mapped backgrounds, the SWIV editor was sprite-based. It gave the game a very unique look." Another benefit of Pieket's system was the ability to create large maps - in SWIV's case, one very long map for the entire game. "The editor allowed Ned to place colour palette changes that scrolled in sync with the background, powered by the Amiga's Copper chip. That way, we could make a single map that still had colour variation as the game progressed."

The Copper - essentially a coprocessor buried inside one of the Amiga's chips - proved a precious ally to designers such as Pieket and Langman. "The various zones did have defining themes," recalls the latter, "but they were blended into each other as it scrolled. It was challenging creating the maps with the colour palette constantly changing; if I couldn't get the colours to blend from one theme to another, sometimes I'd just mask the change with scenery comprised of sprites." Dubbed the Dynamic Loading System by The Sales Curve and used to promotional effect on its packaging, SWIV's continual non-stop action (in its 16-bit versions) was a significant selling point. "It was a real feat of technical skill," says Cavanagh. "The illusion of a single, unbroken attack run, the equivalent of 236 screens with no data-accessing pauses." Fortunately, an adaptive difficulty level, based on the time played without losing a life, helps players through the incessant wave of enemies.

Langman and Pieket's efforts produced a sleek, beautiful and fun shoot-'em-up that owes a few debts to the Tecmo classic. Says Langman, "The 'Goose Copter' was basically a copy of the Silkworm boss. Various little copters join together to form one big craft. The look was different, but the idea was the same." And like the previous game, two players can play simultaneously, one in charge of a helicopter, the other a sturdy jeep. With the freedom to develop their game away from the constrictions of an arcade licence, references to Thunderbirds and other arcade games - such as the old Namco game, Xevious - were shoehorned in. Often cited as one of the greatest shoot-'em-ups on the Commodore Amiga, Andrew Barnabas's jaunty music became the icing on the cake, alongside some impressive vehicle schematic design during its intro. "Oh yeah, I'm very proud of those!" grins Langman. "I think the opening credits of Terrahawks influenced me, and it's a cheap trick, really. Each layer of the vehicle is drawn in one colour of the palette. All the colours were then turned to black, then green one at a time. Simple but effective!"

Released in the spring of 1991, SWIV received a glowing reception in the 16-bit press. "Glorious graphics, sound that goes beyond the functional and that elusive 'one more try' factor make SWIV an essential purchase for blasting fans," gushed The One magazine. The only dissenting voices usually cited SWIV's high level of difficulty. "It did get relentlessly hard later on," admits Langman, "but it was very playable if you levelled up your firepower properly and got into the zone. I've always been very happy with what we did - we certainly had many ideas we never had time to put in." Beautiful, humorous (alien ships leave crop circles, shopping trolleys litter empty riverbeds) and inventive, SWIV already had enough ideas for a dozen games.

Beyond the good reviews, it was the sales of SWIV that had the biggest effect, especially for its nascent publisher. "The success of SWIV - and Silkworm - were enormously important to The Sales Curve," reveals Cavanagh. "These titles and the creative team behind them really launched the company." Five years later, The Sales Curve became SCI Entertainment Group and floated on the London Stock Exchange. Those little jeeps and helicopters of Silkworm and SWIV forged its success. "I have extremely fond memories of that time," says Cavanagh. "It was very early days for the company and very exciting. Having two early hits was just amazing - I'm particularly proud of them and grateful to the team that created them." The success of SWIV also defined the career of its developers, as Pieket tells. "SWIV was pivotal for me: its popularity opened many doors, and I still get the occasional 'Oh my God, you wrote SWIV?' comment." And finally, for Ned Langman, it's a love that's never entirely gone away. "I've never abandoned SWIV as it was the most fun I've ever had making a game!" he smiles. "Maybe one day I'll get around to that unofficial follow-up..."