The history of game hints pages, before the internet took over

POKEs, maps and cheats.

I'm stuck on Starfield. There are a million mission icons dotted around the screen, and I keep getting my ass handed to me in space by a bunch of pirates. Fortunately, it's 2023. I grab my smartphone, and within a few seconds, I'm looking at a page from Eurogamer's excellent guide to the Bethesda space epic. Ah, I press that button - now, only my current mission icon shows up. And I need to upgrade my ship. Or buy a better one. Here are the best ones, how much they cost and where to get them. Job done.

Rewind almost 40 years. I'm stumped on Ultimate's latest isometric epic, Pentagram. In typical Ultimate style, the instructions are eloquent but useless. I'm wandering around, exploring the two-colour world, occasionally jumping over blocks and avoiding the odd nasty. Eurogamer is just a twinkle in its founder's eyes, and in any case, how would I access it? The concept of networking computers was gathering pace, but it would be many years before the internet, as we know it today, would be available to proles such as me.

So, we networked, old school style and tips and tricks were swapped in the playground. But that didn't always work, especially with tougher games like Pentagram. There was one avenue left. Our internet, our network of (in my case) Spectrum fans, eagerly engaging with the experts and each other: the games magazines.

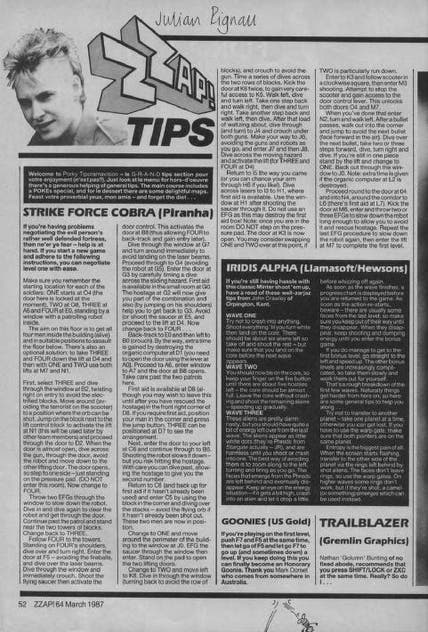

In 1981, author Tom Hirschfeld released one of the first tips books, How To Master Video Games. "I remember reading that and thinking, 'holy shit, you can write about these video games and do tips for them,'" grins Julian 'Jaz' Rignall, one of the earliest games tips writers in the UK. "So when I came home from winning the arcade championship in 1983 and having this legitimacy of being a good player, I thought, well, I'll start writing hints and tips." At the time, the UK's premier games magazine was Computer & Video Games - or C&VG. "The first thing I wrote was a guide to playing the Atari arcade game Pole Position," continues Rignall. "I'd mastered the game over the summer and wrote this corner-by-corner guide. There was no template; it was just about how to drive around the track along with specific hints."

The idea caught on, and Rignall began writing tips for Personal Computer Games, one of the first British magazines to feature a regular tips section. By the time Newsfield began its famous Commodore 64 bible, ZZAP! 64 in the Spring of 1985, everyone knew the importance of a regular section dedicated to helping gamers. "It was a very important part of the magazine," notes Rignall. "Market research showed that the tips were, along with reviews, the most popular parts of the magazine - but we had a gut feeling it was anyway, and it meant a lot of interaction with the readers."

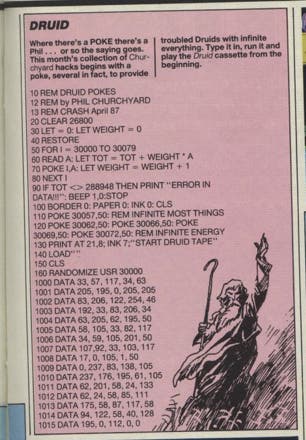

Each issue of ZZAP! 64 included four to six pages of tips, hints, cheats and POKEs, almost all of them sent in by readers. The latter - a short type-in program that gave the player infinite lives or some other advantage - was critical. "The turnaround on POKEs was quick," recalls Rignall. "Those guys had their routine, and I literally called them up and would ask for some POKEs for as soon as a game came out."

Occasionally, the magazine would even send games to hackers - anything to promptly get the POKEs into the mag.

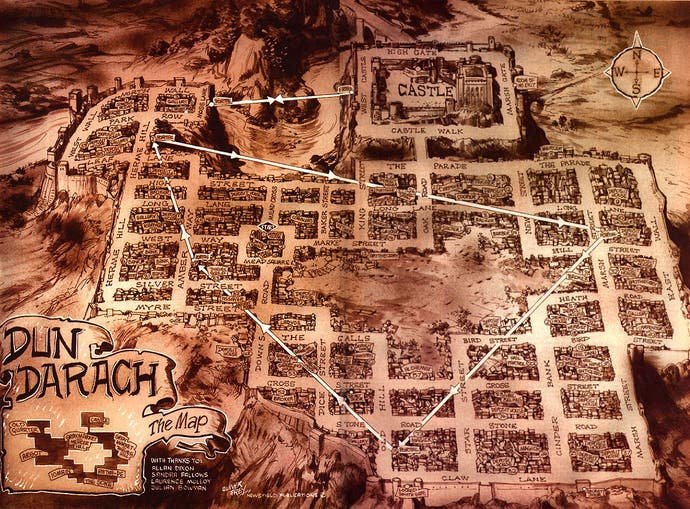

Over at ZZAP! 64's sister mag, Crash, its early issues had been conspicuously without tips. The editorial department soon caught on. "I remember as a reader, the big deal of the Atic Atac map," recalls Nick Roberts, who compiled the tips section in Crash a few years later. "They ran a competition for readers, then Oli Frey turned these lined paper and pencil sketches into a map of beauty, with the prize of a cool ACG trophy!" In addition to providing the covers, a regular comic strip and other titbits of art, Newsfield co-founder Oli Frey often studied readers' maps, converting them into artistic wonders that wouldn't look out of place on a wall. With many Spectrum games (such as Atic Atac) running into hundreds of screens, it was easy to get lost. Boy, we treasured the maps.

Of course, it wasn't just Newsfield that had a tips-related epiphany. Crash's rival, Your Sinclair, quickly realised it needed a tips section, and, typically, the skillo YS decided to do things a little differently with two different columns: Hack Free Zone for tips and cheats, Hacking Away for POKEs. "I suspect it was because anyone can read a tip and try it," says erstwhile Your Sinclair staff writer Phil South, "but inserting POKEs required a bit more savvy." Writing under the pseudonym Hex Loader, South opened the mail from readers, tested the submissions and transcribed everything into the two sections. "[It] was valuable to the readers, and the more of that we could do, the more value we would add to the magazine," he adds. "Plus, the research and testing of the tips was 80 percent done, and all I had to do was find out if they worked and write a few jokes in response." Persistent mappers, such as a young lad named Mischa Welsh, even found themselves hired by the magazine to produce regular content, and Your Sinclair went beyond the usual mere name-checks, printing photos and profiles of anyone brave enough to send them in with their tips.

As readers, we would absorb all these hints, maps and cheats, diligently type in the POKEs - sometimes, they would even work - before enjoying a fresh lease of life with the respective game. While every other section of the magazines was carefully constructed by its staff writers and freelancers, this was one of two parts (together with the letters pages) that was more reader-created. "The process started with a giant postbag," smiles Roberts. "We received hundreds of letters a month, and it was my job to sift through them and find some interesting ones for the Playing Tips pages." Using a green-screen Amstrad PCW8256, Roberts typed up each tip with a small introductory paragraph and a name-check for the submitting reader. "I was told how many pages I had in each issue and made a flat plan, setting out what went where. If we had a good map, we could use that as is, while POKE routines were the bread-and-butter of the tips pages." As for all these tipsters, Roberts had to locate the POKE's game and test the routine before typing it up - carefully - for the magazine. The final piece was the introduction paragraph. Muses Roberts, "Looking back now, those Playing Tips pages act like a diary of my teenage years - there's talk of my fledgling DJ career, dalliances with the ladies, what I was up to at Christmas and the holidays. Great fun to look back on."

Not everyone feels the same. "As a journalist, it wasn't enjoyable at all," grimaces Rignall, who endured stints as tip master at both ZZAP! 64 and Newsfield's Amstrad magazine, Amtix. "All you were doing was copy-pasting, copying people's letters and looking at POKEs - it was incredibly tedious!" Timing was an issue, too; the magazine would require long-form guides for games that wouldn't even be on the shelves when the reviews came out. That job, inevitably, fell to staff writers. Your Sinclair's Phil South echoes Rignall's thoughts. "It was a breeze, apart from the laborious re-typing of everything. All I had to do was come up with some good jokes. Actually, that pretty much sums up my entire journalistic career." Eventually, Your Sinclair merged its two sections into one glorious Tips spread: with South moving to other duties, colleague Marcus Berkmann stepped into the world of hints and POKEs. "He was a very meticulous cove, old Berkbilge," laughs South. "He had very tiny precise handwriting that looked like notes taken by miniature spiders."

Coveted by readers, the tips pages engendered mixed emotions for the journalists behind them. As the 8-bit era subsided, games became less esoteric but more complex. Long-form guides became the order of the day as that mainstay of the Eighties mags, the humble POKE, slowly faded into obscurity. "I reckon it peaked around 1994," says Rignall, "and then just slowly faded at the end of the 'nineties. As soon as I saw Gamefaqs, I thought it was just brilliant and would nuke the need for magazine hints and tips. You could get them straight away, and people were doing it for free, these unbelievably detailed text guides."

Having cut his teeth as a 'Games Counsellor' on the Nintendo Hotline, an official service run by Nintendo to provide tips and help for its games, journalist Keith Pullin joined PC Zone in the late 'nineties. Incredibly, one of his first roles was writing an 'agony aunt' style tips section called Dear Keith. "The weird thing was, it was mostly still letters, actual snail mail," he tells me. "There was an art to finding the ones to publish and respond to, and the holy grail was finding a game that was reasonably popular and current, so people would be interested in it." This was part of a larger tips section, and similar to Crash's adventure column in the Eighties: readers requested a hint or tip, and Pullin responded. Well, if he could. "Quite often [the letters] just didn't make sense," he grins. "The one piece of information that people tended to forget to mention was the name of the game!" Pullin also took over the guides section, writing enormous pieces dedicated to one game in particular. "You'd contact the publisher or developer to try and get cheats, level skips, game saves - anything to dull the pain. Then, you had to get precise screenshots of the exact thing you were talking about. It was probably some of the most gruelling work I've ever done." And that wasn't even the most challenging part. "That was editing it all down to 2500 words. It meant that a level on something like Carmageddon 2 would be distilled down to 'Kill everyone. Jump the gap. Enter the shopping mall. Kill everyone. Exit the mall.' I often wondered if this level of vagueness actually helped anyone."

Critically, while the tips pages persisted in magazines such as PC Zone, they weren't regarded as integral as in previous years. Keith Pullin wrote his final Dear Keith in 2001; the same year saw his last guide for PC Zone appear, and by this stage, he was pulling much of the information from the internet. Cheat codes and guides persisted throughout the 'noughties in various games magazines, and there were even dedicated tips mags such as the long-running PowerStation. But it wasn't to last. The internet had won.

Tips and guides are now instantly accessible, but it wasn't the tips that endeared these sections to us back in the day. It may have been a complete pain testing those POKEs and typing them all out for journalists such as Julian Rignall - but for us readers, it was the interactivity with the magazines, our conduit into the world of the ZX Spectrum or Commodore 64. "Magazines were always about being part of a club," reminisces Nick Roberts. "So I feel that for a long time, readers have continued to want to be a part of that club. The internet has never really replaced that."