The Fallout game that time forgot

When The Brotherhood saved man.

It's fair to say the reaction to Fallout 76, which is due out next week, has not been universally positive. With the move to a primarily online mode for the post-apocalyptic series still causing upset among fans, it's easy to forget there's a precedent here, from way back when publisher Interplay held the Fallout reins. Bethesda will no doubt be hoping the Fallout 76 story ends a little better than that of Fallout: Brotherhood Of Steel, a tale that begins not with Fallout, but another famous RPG series from the late 90s.

Since the release and astonishing success of BioWare's Baldur's Gate, Interplay had been pondering on how to expand its IP to consoles. A PlayStation port of the original game - which worked as a push-scroll/flip screen game - was almost completed by developer Runecraft, before Interplay's takeover by Titus Interactive caused that and many other projects to be cancelled.

Then finally, in 2001, came Baldur's Gate: Dark Alliance. Based on the technically-impressive eponymous engine by Snowblind Studios, Dark Alliance greatly simplified the RPG experience, reducing interaction to short soundbites, inventory management to an equip/unequip list and the combat to hack 'n' slash, mixed in with some dramatic, but limited, spells and ranged weapons. The console-playing public lapped up this new spin on the RPG genre, and Dark Alliance was a best-seller across the PlayStation 2, Xbox and, eventually, Nintendo GameCube. So why should its publisher not try and repeat the trick with its other great RPG series?

The concept of a console Fallout game had been kicked around Interplay for some time, and long before development began on FO:BOS. "I thought it was a great idea," says Chris Pasetto, lead designer on the game. "Interplay had been mainly a PC company up until that point. We were part of a scrappy new division charged with expanding into the console market, with both new IPs as well as old ones." In the latter case, Fallout was the name on everybody's lips, and, long before Bethesda would revolutionise the series with Fallout 3, Pasetto's team even pitched a first-person shooter.

"We knew a little about what Black Isle was planning for their version of Fallout 3 aka Van Buren, and wanted to make something different for the consoles." But then came the new Baldur's Gate game with its fancy engine and sleek, action-focused gameplay. "Don't get me wrong, I liked Dark Alliance a lot," remembers Pasetto. "But it's a pretty barebones rendition of the D&D world, without much depth or open-endeness. The success of it influenced a lot of people, and for better or worse it dictated our course on Brotherhood Of Steel."

The idea was a sound one, at least financially, and with Pasetto at the helm, the game at least had a fan of the series at its heart. "Fallout 1 and 2 are easily in my top 10 games of all time," he declares. "I have fond memories of those first steps out of the vault, firing an SMG at a raider point-blank, and deciding who to side with, Killian or Gizmo." But once the Snowblind engine was co-opted, any deviation from the rigid template, technology and design, was an uphill battle.

"We didn't have the engineering bandwidth to do more than a few tweaks," notes Pasetto. "Our main technical focus was improving the ranged combat for the gun-focused gameplay of Fallout." So an action-focused, bare-bones console version of Fallout - that doesn't so bad, does it? Why the spitting venom from fans of the post-apocalyptic RPG? The answer is simple: they messed with the lore.

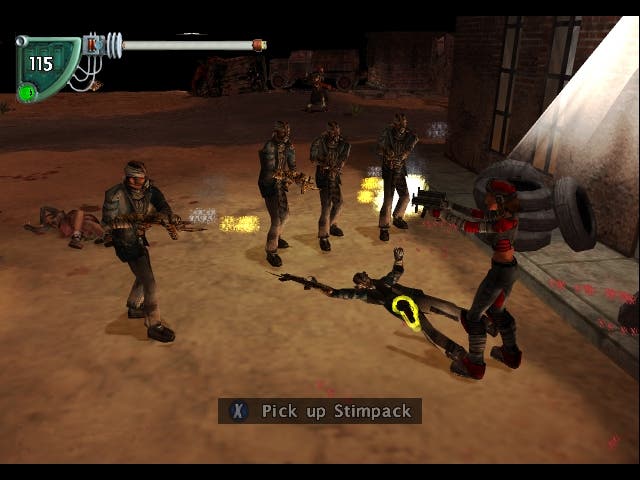

"So much of what was quintessentially Fallout got dumbed down," sighs Pasetto. The Brotherhood of Steel, the focus of the game - as its title would suggest - were transformed into noble peacekeepers, reining in the ne'er-do-wells of the wasteland, its chief role as a preserver of technology seemingly forgotten. "The stuffy, pseudo-religious techno knights of the Brotherhood weren't sexy enough for the perceived console market," Pasetto sighs again. "They turned into scantily-clad heroes of the wasteland, who occasionally put on power armour to battle evil."

The influence of Interplay's new management-level staff appeared to be playing a role in moving wholesale away from the type of games the company had made its name with. "Because maybe they'd done the intelligent, mature, games that garnered critical acclaim, but were financially unsuccessful," ponders Pasetto. "So new management came in, and swung the pendulum far in the other direction, although of course that's just my opinion. We brought up our concerns up about dumbing down Fallout from the start, but [management] insisted Brotherhood of Steel should be - had to be - an action game, not an RPG."

Another effect of the pendulum swing was a notable obsession with sex. In addition to the scanty outfits of many wasteland inhabitants, the very first NPC the player interacts with is a prostitute named Ruby. Moreover, instead of the twee 50s music of the original games, modern alt-rock such as Slipknot and Killswitch Engage peppers the game. And most heinously, gone was that famous caffeine jolt, the chemically-dubious Nuka Cola, replaced with the real-life Bawls Guarana, a tie-in that no doubt brought financial side-gains to the troubled Interplay. Pasetto admits that while the product placement jarred, there was little he or his development team could do about it.

"I think overall the alternate retro-future aesthetic was missing, deemed too weird. Brotherhood Of Steel's vibe was much more generic post-apocalyptic, which was a real shame." Like practically every management discussion, the perception of what the modern console market wanted drove these decisions. "...and that, was the end of it," shrugs Pasetto. Then, when Brotherhood of Steel was announced, the public opprobrium began in earnest. "The whole team was aware of the criticisms - we shared them," laments the designer. "The problem wasn't bringing Fallout to consoles, and it wasn't removing turn-based combat in favour of real-time. The problem was that we removing the style and depth of a Fallout experience, and any argument to do something like the original Fallout games was met with 'That's not how Dark Alliance did it'."

Planned as a short-term money-maker using existing tech to take advantage of a well-known IP, Fallout: Brotherhood of Steel even failed in this respect. Met with negative press and poor sales, it was highly unlikely to ever have been Interplay's knight in shining armour. "It was just one of many projects that underperformed and would have had to sell miraculous numbers to change the fate of Interplay," notes Pasetto sadly. "When it came out and got so much bad press, the development team was pretty demoralised. It was a tough time, to put it mildly."

Given how Fallout 3 changed the world's perception of the series, firmly and successfully onto consoles, this PlayStation 2 and Xbox game surely had potential (PC and GameCube ports were inevitably abandoned early on, if realistically considered at all). Does Pasetto think things could have turned out differently? "If I have one major regret with Brotherhood of Steel, I wish I'd worked harder to convince Interplay to take more risks with the game. I wish we'd quietly peeled off a few people to create a quick prototype of what a more authentic Fallout console game could be.

"Even if we'd been restricted to the Dark Alliance engine, we could have certainly made something more engaging, and Fallout-ish. Maybe it wouldn't have made a difference, given the atmosphere at Interplay; but it would have been worth the extra effort up front."

Chris Pasetto left Interplay shortly after Brotherhood of Steel, enduring a mild crisis of faith, and determined to re-evaluate what he was doing, and how. Then, four years later, he found equal redemption and frustration with Bethesda's Fallout 3. "My first playthrough was a ridiculous number of hours, easily over a hundred; I scoured that map like a Zamboni, clearing every inch of the ice rink. I also spent a lot of that time grinding my teeth, thinking about all the nay-sayers who claimed that a Fallout RPG would never sell on consoles."

My interview with Brotherhood Of Steel's designer finishes with a standard closing question: Is there anything else he'd like to add on Interplay's final Fallout game that would interest readers? "Wow. Um, just that this has been incredibly painful..." he says slowly. Considering the game is now considered ousted from the Fallout canon, no wonder it still hurts. Sometimes, war does change.