Saturday Soapbox: The Outsiders

Let's hear it for isolation.

If you're a fan of This American Life, you might be familiar with Jack Hitt. He provides the wry, rather sweet voice that leads you through some of the show's best episodes - most notably Act V, which took listeners inside a US prison to watch in-mates putting on a performance of Hamlet.

I've just finished reading Hitt's new book. It's called Bunch of Amateurs: A Search for the American Character, and it's a wonderfully wayward analysis of the contributions made by tinkerers, hobbyists, and those who lurk just outside of established professions. It's a short work, but it touches on a terrifyingly vast range of topics, from the homebrew gene-hacking movement to Dobsonian telescopes and the early belief that America's native wildlife was so sickly and ineffectual that the country's bears could only subdue cows by biting a hole in their sides, and then blowing into the hole until the cow in question exploded.

If you ask me, it's an excellent read - especially if you're interested in bovine apocrypha - and even though it doesn't tackle video games directly, it made me think about them quite a bit. Here's why.

One of the most engaging ideas Hitt explores is something that we've probably all heard about before: the notion that working outside of a system - as an amateur, for example - allows you certain benefits that aren't always available to those within the system. You'll have seen this concept celebrated in every summer movie where a downtrodden yet roguishly handsome professor gives a mercurial expositionary lecture while crowds of starched-shirt poshos walk out jeering, and in every cop show, where the only guy who can catch this darn killer is a crank who lives in his car, juggles a couple of ex-wives, and was thrown off the force years ago for telling the chief to sit on a pencil.

At heart, the argument tends to be pretty straightforward: outsiders sometimes have an edge because they aren't as likely to be cursed with an insider's knowledge of what is and isn't deemed possible or sensible. They haven't been taught the rules, and on the occasions that the rules turn out to be wrong, they aren't necessarily quite so limited by them. Being on the inside might save you from plenty of costly mistakes and heartbreak, in other words, but there's also a very slight chance that, now and then, it might be holding you back from innovation. It might be stopping you from making that bold creative leap, and doing something amazing.

It's a romantic idea, and it's one that I find fairly appealing - and that's not just because I've clearly never been close to attaining a professional standard at anything whatsoever. I find it appealing because, shortly before I first opened Hitt's book, I met Simon Read at this year's Develop conference in Brighton, and, retrospectively, Read seems to be a very good example of what Bunch of Amateurs is on about.

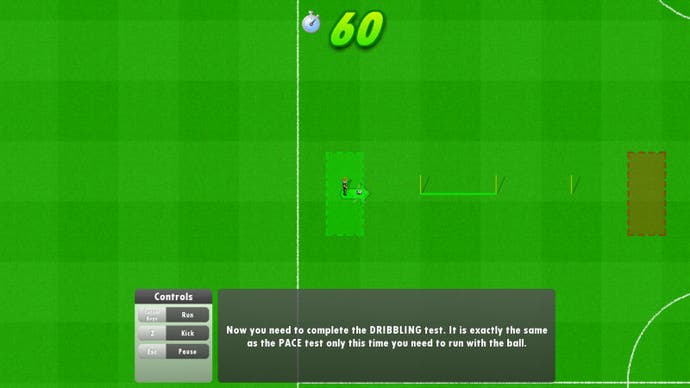

This particular story is already turning into game design lore, of course, but let's go over it one more time. Read started making games as a hobby, and eventually quit his day job because the hobby was paying so well. For the best part of a decade, he slogged away at New Star Soccer, a series of quirky football management titles that garnered a loyal, but fairly select, audience on PC. This year, though, he released the game on mobile, and after a review in The Sun it all went mental. Everywhere I looked at Develop, somebody was either raving about New Star Soccer, or admitting they'd had to delete it from their phone because it was ruining their lives. It was the game everyone in the industry was obsessed with, and it's going to go down as one of the defining titles of 2012.

And yet when I met Read, I realised he largely existed outside of the industry itself, and I started to wonder whether the traditional world of publishers and developers could have even created something like New Star Soccer. It's an odd blend of genres and playing mechanics, for one thing, and it's had to undergo several sequels and iterations - and a platform shift - before finally landing a mass audience. It's not insanely inventive, necessarily, but it is eccentric - just eccentric enough, perhaps, to make an established design team second-guess themselves.

Could a big publisher have released NSS? Possibly. Somebody brought Football Manager to the masses, after all, and that must have seemed like an odd idea. It doesn't feel enormously likely, though, just as I can't imagine Manic Miner would have been the game it is today, for example, if Bobby Kotick was flinging art assets out at focus groups. "A toilet that kills people, Smith? Sensational! And the old ladies in Peoria are eatin' it up too!"

How many people internally would Read have to had run his game design by in order to get production up and running? How much would the first game have had to sell to ensure a second one? Would he have even come up with the idea if he was moving between work on huge triple-A projects all the time?

The danger of Hitt's argument - and it's a danger that, in the book, he's happy to explore in full, and from many angles - is that you can end up determined to believe that professionalism is over-rated: anybody on the inside becomes The Man, and everyone on the outside is instantly some glorious genius, brimming with the right ideas.

This clearly isn't true. Publishers and big developers turn out brilliant, inventive, creative, unlikely games with surprising frequency, of course, and sometimes, when people tell you your cherished homebrew project is raw and stupid and should probably be dropped in the ocean and then dive-bombed, it really is a stupid idea, and you possibly should think of trying something else. It's also a little too easy to turn the whole thing into a weird slight at gifted outsiders, too. Read didn't create NSS simply because he worked in isolation. He's a talented designer with a good idea, and he's put the hours in.

Outsiders - indies, hobbyists, amateurs, micro-teams - are increasingly creating a lot of the really good stuff, though, just as, every day, more and more of the announcement emails that end up in my inbox aren't from the PR firms from big publishers ready to tell me about triple-A shooters, but hail instead from bedroom coders who have thrown two or three bizarre mechanics together and created something weird and wonderful.

It's not about rejecting professionalism, for these guys, I suspect, but about stepping back every now and then and maybe taking the odd holiday from some of the things that come with the professional's approach. While they're on their holidays, of course, I do hope they stay away from any bears they may spot. I gather that some of those American ones can be very dangerous.