Noodle stands and acid rain: four decades of gaming's urban dystopias

Sunglasses at night.

It's becoming increasingly hard to remember a time when we visualised our metropolitan future differently: no rain-polished streets reflecting the glare of neon signs, no fetid slums nestled snugly around imposing high-rises, no collective mass of humanity wearing the marks of economic oppression and state-sanctioned violence in their purposeless haste, their hunched postures, their fearful silence. In other words, it's becoming increasingly hard to remember how we imagined urban dystopias before the iconography of Blade Runner gatecrashed our collective consciousness and etched its initials on the concept.

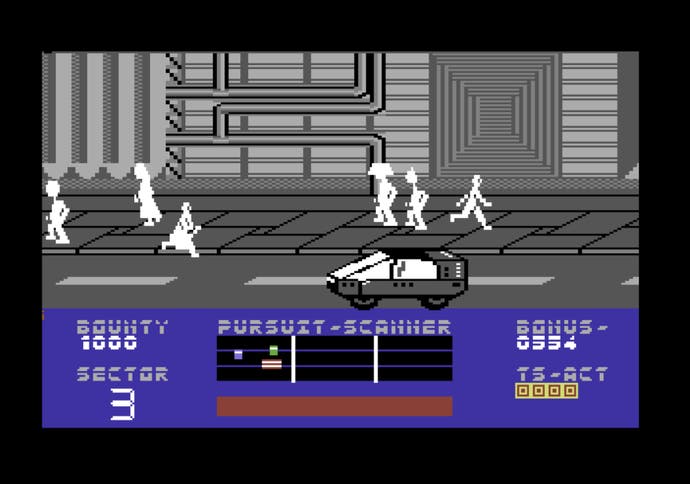

Given the momentous impact of Ridley Scott's film and our medium's affinity for science fiction, it may seem a little odd that video games didn't rush to exploit this grimy, evocative setting. For comparison's sake, E.T. the Extra Terrestrial was theatrically released within the same month as Blade Runner, June 1982. Whereas the former was adapted (albeit disastrously) before the year was over, we didn't get the chance to play Deckard until 1985 and, though nowhere near as infamous, CRL's effort wasn't much of an improvement, its "replidroid" chases requiring an impossible combination of split-second decisions and pixel-perfect accuracy to switch safely between crowded pavement and oncoming traffic in order to keep up with your quarry. Why the delayed response, especially in the unregulated wildlands of early '80s game development where acquiring legal rights wasn't necessarily a priority?

Taking a closer look at some of the more enduring tropes associated with the film, the reasons we have virtually no dystopian games from the first half of the decade become evident. Blade Runner did not feature a single overarching catastrophe, a war or an alien invasion, forcing a clear distinction between enemies and allies. An illusion of social stability is essential to urban dystopias; whatever threat we have to deal with, whether a replicant or a corrupt politician, typically comes from within. The challenge lies not so much with neutralising it, as with identifying it. Moreover, the introspective nature of the subgenre, an obvious debt to its film-noir roots, almost invariably leads to its most characteristic twist: a questioning of (and usually shift in) allegiances.

These conventions, part and parcel of the setting, do not lend themselves readily to the simplistic shooting galleries of that era. They require advanced storytelling techniques: detailed characterisation, and a discernible narrative whose progression entails more than killing stuff to amass points. Such were the complex demands made on the still nascent art of game design to produce a properly dystopian setting, not to mention the absolute nightmare of animating a halfway convincing trenchcoat in a 320x200 resolution.

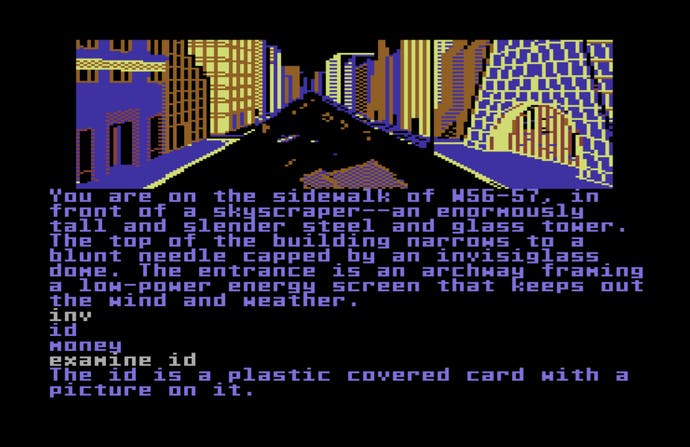

It is not particularly surprising then, that it took so long for the industry to catch up, nor that gaming's earliest urban dystopias appeared in the only genre capable of delivering nuanced storytelling at the time: text adventures. In 1984, the American software company Telarium published Fahrenheit 451, arguably the first fully-formed example of the setting in a video game. As was its wont, Telarium had secured a prestigious collaboration with the titular novel's author to produce what was, rather confusingly, a semi-canonical sequel to his story about a tyrannical regime seeking to eradicate all books.

The degree to which Bradbury participated in the project is debatable (he wrote the blurb on the box at the very least, and, supposedly, provided some of the dialogue), but the game, despite typical genre issues like obscure puzzles and an excruciatingly obstinate parser, stays true to the spirit of the novel. What ties Fahrenheit 451 to the tradition of urban dystopias is not just the narrative, which sees the return of protagonist Guy Montag to rescue long-time companion and resistance member Clarisse McLellan from the authorities, but also the wonderfully dark, grainy visuals of dreary downtown New York, seemingly more indebted to Scott's depiction of future LA than the relatively bright palette of Francois Truffaut's 1966 film version.

After a handful of awkward adaptations that unsuccessfully attempted to instil complexity by splicing convoluted interfaces with more traditional arcade sections (both CRL's Blade Runner and Quicksilva's Max Headroom fall in this category) the watershed moment for the emerging subgenre came in 1988 with the release of Sierra's Manhunter: New York, Interplay's Neuromancer and Konami's Snatcher. It wasn't so much the quality of that fateful batch, rather the fact all three titles encapsulated the industry's frustrations with text adventures and contributed, each in their own way, to the tectonic shift towards other forms of input.

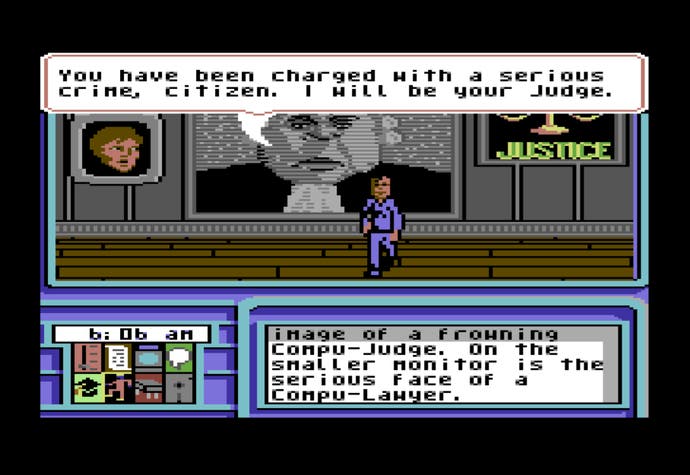

Manhunter, the rare example of a dystopia imposed by an outside threat - alien orbs policing all communication between humans - was significant as the first Sierra title to abandon the parser in favour of a multi-purpose cursor. Snatcher, Hideo Kojima's infuriatingly unobtainable early classic, whose robotic antagonists, not unlike replicants, hide in plain sight, experimented with preset commands. But it was Neuromancer, another loose literary adaptation, that came closest to emerging point 'n' click trends by featuring a cluster of icons which allowed players to carry out conversations, make online transactions and placate the Chiba City authorities which had the annoying habit of dropping you off at the Kwik-E-Court for a summary trial and 500 credit fine. With those three titles, gaming dystopias attached themselves to the rapidly evolving adventure genre that would dominate the coming decade.

Self-doubting antiheroes, seedy back alleys and greedy corporations were all the rage in the '90s, from traditional point 'n' clicks such as Dynamix's Rise of the Dragon and Empire's Dreamweb (featuring different descriptions for each of your two shoes - further proof, surely, of the subgenre's fashion obsession), to hybrid RPG/adventures such as the three unconnected Shadowrun games released as platform exclusives for the Megadrive, SNES and Mega-CD. With compact discs enhancing storage capacities, FMV "interactive movies" could soon combine bad acting and lo-res video into new visions of urban apocalypse, often with hilarious results, whether intentional (Under a Killing Moon), or not (Ripper). Then, in 1997, as the popularity of adventures waned, we finally got the adaptation we had been waiting for.

In what was fast becoming a subgenre tradition, Westwood's Blade Runner was intended as a sort of transmedial sequel. A captivating experiment in narrative construction, it managed to tell a different - and, by some measures, equally compelling - story, while not simply taking advantage of the film's locations, but, on several memorable instances, the exact framing and composition of individual shots. Running parallel to Deckard's story, our reluctant protagonist Ray McCoy must track down the replicants responsible for butchering the expensive stock of an upscale establishment dealing in rare living animals. A premise bursting with symbolic charge, an ever-expanding mire of interweaving conspiracies to drown your affiliations in and some intense Voight-Kampff test sequences bring this close to the interactive movie ideal of the time, one, however, the industry was gradually moving away from.

The '90s gave us a Blade Runner game, but for this industry's Blade Runner moment, a dystopian work so influential it would send shockwaves throughout the medium, we'd have to wait for the turn of the millennium. Deus Ex has been covered extensively elsewhere (not least in one of Eurogamer's earliest perfect scores), so it should suffice to say its open-ended design, its seamless fusion of action and RPG elements and its labyrinthine conspiracies have inspired numerous homages and imitations, even as its staggering ambition remains unsurpassed. In an intriguing little parallel with Blade Runner, both works came out with quite a few hitches, eventually smoothed over in subsequent iterations: Scott's alternative cuts and the various patches dealing with the game's more serious issues.

Whether as irony of video game history or as understandable anxiety of influence, it was only after Deus Ex provided the ultimate blueprint for gaming dystopias that high-profile developers started experimenting with their long-established aesthetic. Jet Set Radio Future expanded their visual repertory by adding some colour and even (heresy!) daylight to their palette before the blinding brightness of Crackdown and Mirror's Edge brashly overturned the paradigm. If the permanent gloom of traditional dystopias was meant to underline environmental devastation and street-level poverty, then the unrelenting glare of Mirror's Edge and the panopticon-like skyscrapers of Crackdown spoke to a different, post-millennial concern: unchecked surveillance.

These open vistas and vivid colours are carried over beautifully to the isometric city of Tokyo 42, a title emblematic of the medium's growing fascination not just with the subject of urban dystopias, but also with its own history. More than ever, contemporary developers are keen to dig gaming's past for references to enrich their worlds, whether by repurposing long-abandoned franchises in the reboot of Deus Ex and the recent Dreamfall: Chapters; championing outmoded genres in Wadjet Eye's lovingly crafted adventures; or by highlighting neglected classics in Satellite Reign's homage to Bullfrog's Syndicate.

At the same time, we can see glimpses of a more sophisticated outlook from a subgenre that used to wear its politics like a fashion accessory, its edgy, shallow rebelliousness collapsing under its own contradictions: Remember Me's naive assertion that the answer to structural inequality lies in convincing powerful CEOs to play nice, or Ruiner's failure to comprehend that female empowerment cannot really work while adhering to odious stereotypes. Games such as VA-11 Hall-A and Quadrilateral Cowboy complement these otherwise enjoyable but politically meaningless titles by being willing to scrutinise the nitty-gritty of the underprivileged life without glamorising it via sunglasses and trenchcoats. Between this kind of emerging sophistication, a fertile awareness of their historical roots and a newfound adaptability to every conceivable genre, from sombre walking simulators to hectic twin-stick shooters, as paradoxical as it sounds, the future of gaming dystopias looks bright indeed.