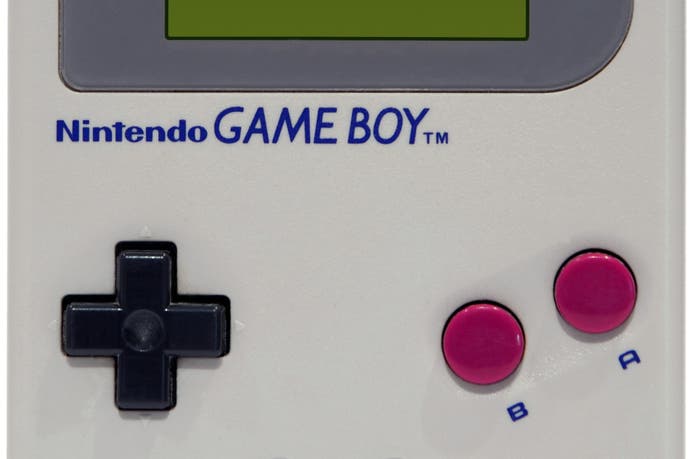

Game Boy got soul

How the simple heart of Gunpei Yokoi's Game Boy has a legacy that goes beyond hardware.

"In video games," Game Boy designer Gunpei Yokoi once said, "there is always an easy way out if you don't have any good ideas."

The recent 25th anniversary of the original Game Boy's release has provided a perfect moment to celebrate the contribution of the sadly long-departed Yokoi to the world of video games, and it's also provided a perfect excuse to delve further into some of Yokoi's many brilliant ideas . Some of them are better known than others: there's the Ultra Hand, the toy tongs invented in the designer's downtime during his first job at Nintendo tending to the company's card manufacture machines, and a device whose success would lead president Hiroshi Yamauchi to give Yokoi his own R&D department. There's the Love Tester, an endearingly trashy toy created, Yokoi once said no doubt with an impudent sparkle in his eyes, to see if he could get more girls to hold his hand, and of course there's the Game & Watch, whose d-pad was at the vanguard of Nintendo's move into households across the world with the Famicom and NES.

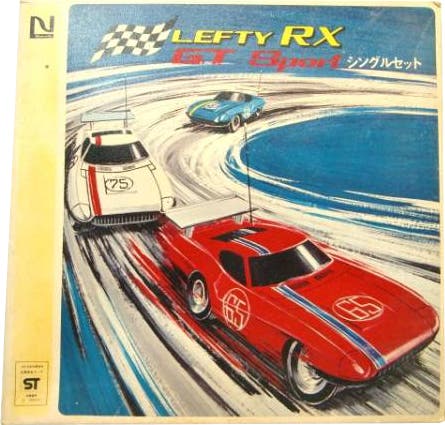

But it's another slightly more obscure creation that I think sees Yokoi at his best. Developed at a time when remote-controlled cars were a high-budget object of real desire for the discerning child, the Lefty RX is, on looks alone, beautiful. The sleek body blends together the elongated, elegant lines of 70s Japanese automotive icons like the Nissan Fairlady Z and Toyota 2000GT, its squat plastic shell and rubber tires making it a joyously robust play-thing. Its master-stroke, though, is hinted at in the name: in order to keep costs low, and in order to make what was typically prohibitively expensive available to the masses, the parts were stripped back and simplified to the extent that the car could only ever turn left.

With one smart move Yokoi and Nintendo were able to undercut the competition to create a toy that was exquisite in its simplicity, and its success soon outstripped its inadequacies - when one or more Lefty RXs were pitted against each other, the fact they could only ever turn left was made redundant as they raced around in energetic circles. It's one of my favourite examples of Yokoi's oft-repeated philosophy - the idea of lateral thinking with seasoned technology - that manifested itself most famously in the Game Boy. Yokoi's handheld was poorly equipped in terms of power and fidelity when placed against its rivals the Atari Lynx and Sega Game Gear, yet its ability to extract 35 hours out of four AA batteries and its bold simplicity ensured it did so much more than just win out.

When Yokoi was talking about the easy way out, he was referring to the hardware war that raged around him in the mid-90s, a war that continues to be waged on new fronts today. "That's what the CPU competition and colour competition are about," he said as he was preparing the ill-fated launch of the Virtual Boy. "But there wouldn't be companies like Nintendo any more who make games in their essence. Eventually, those who're good at screen composition and CG would win, with Nintendo left with no place to stand."

It's fascinating to return to Yokoi's comments today, especially given where Nintendo now stand. The idea of lateral thinking with seasoned technologies has stayed with the company ever since Yokoi's untimely death in 1997, and has seen it through to great success with the Wii, which dared to step away from the burgeoning HD era, as well as the DS, which re-appropriated the Game & Watch's curious form factor to grand effect. It's an idea that has stuck with Nintendo since, too, though both the Wii U and 3DS suggest it's been misinterpreted in subsequent years: the technologies used in both were seasoned by the time they were appropriated, perhaps, but the simplicity which made past Nintendo devices cast in Yokoi's mould a triumph was entirely absent.

So where does Yokoi's legacy lie if it's no longer to be found in Nintendo itself? It's certainly not in the numbing convergence of other contemporary consoles, even if there is a glimmer of it in the simplicity of Sony's PlayStation 4, a machine whose recent success comes down to its single-minded focus on games.

Perhaps it's in Oculus Rift, a device that - it's all too easy to forget in the heated aftermath of the Facebook buyout - was built by a teen hobbyist taping together existing and affordable technology to resurrect an old idea. Certainly the broader, grander vision that both Oculus and Sony has for VR puts me to mind of Yokoi's final ambitions, noted down in the book Gunpei Yokoi's Game House before he ever got a chance to realise them. "I want to try to create something new, by reconciling the world of real things with my world of play," he said. "I want to think about how to bring the fun of games into real-world situations. Call it lateral thinking with seasoned video games!"

Within that slight evolution of his well-known philosophy is, I think, where Yokoi's legacy now lies - in games that take on old, often faded ideas and take them to new and exciting places. You see it in the monochrome pixel-art of a game like Canabalt - whose pared-back control scheme seemed as counter-intuitive to traditional games in 2009 as a remote-control car that could only turn left - and its elegant extension of well-worn mechanics. You see it, too, in the endless caverns of Spelunky carved from Nintendo rock, or in the stocky 16-bit action of Vlambeer's games. It's there in Towerfall's brilliant retooling of Bomberman and Smash Bros, as it is in the heart-wrenching place To The Moon pushes its SNES aesthetic.

It's there, in fact, any where you might look where people have realised that power is always trumped by invention. And perhaps that's the greatest gift that Gunpei Yokoi - and the Game Boy - has given us: a generation of developers full of ideas, and ones who aren't necessarily looking for the easy way out.