Dead Space remake review - a horror original re-engineered as a franchise prequel

Ishimura the merrier.

The not-so-good ship ISG Ishimura is around 62 years old by the time Isaac Clarke arrives there in Dead Space. During its long career as a "planet cracker", this unpleasant hybrid of Nostromo and whaling vessel has been modded and expanded in grander and smaller ways. Even playing a newcomer - part of a small team sent to repair the Ishimura following a loss of comms - you feel that history of alterations as you stomp from sector to sector, fixing up broken systems while demolishing the, as it transpires, horribly mutated undead remnants of the crew.

Each section is an architectural battle between elementary worker needs such as guardrails and the requirements of enormous machines, with the argument typically falling in the machines' favour. The age and quality of the fittings also reflects a corporate class divide: the bridge is a gleaming concert stage with fancy free-standing glass displays, while the mining and maintenance decks are a warren of rust and asteroid debris, with huge turbines roaring away inches overhead. It often feels like more thought has been given to the placing of snack vending machines than life-saving fixtures like O2 dispensers. The aforesaid zombies or "Necromorphs" have set their own stamp on the décor, filling whole decks with carpets of grumpy biomatter, and turning every human-sized vent into an object of menace.

It's not a great place to call home, even if you're an officer, but it's an engrossing play environment - give or take its clownish lore graffiti, anyway. Revisiting the 2008 game last year in anticipation of this year's meticulous but in key respects, disappointing remaster, I was struck by how Dead Space layers up your understanding of the Ishimura by shuttling you back and forth, entering layouts from different angles with different objectives. Admittedly, the fact that literally every mechanism you need to survive has to be fixed grows absurd towards the finish. But the payoff is that the environment feels persistent and alive in a way, say, the prison of spiritual sequel The Callisto Protocol never did for me. Dead Space is celebrated for its devoted yet distinctive spin on Giger - from the outside, the orbiting Ishimura looks like an enormous facehugger drifting above a ruptured egg - but it's the way the game keeps you moving around and reappraising the setting that makes it such an evocative haunted house.

Part of the remaster's intrigue is comparing the Ishimura's in-world history of modification to the developer's own renovations, which broadly aim to recuperate what was once an experimental (by EA's standards) one-off into the larger storyline and franchise Dead Space would spawn. There's the base visual overhaul, which adds details, depths and, indeed, guts to the game's already busy contours. Much as the Necromorphs now consist of layers of tissue that slough away under fire, so hitherto flat walls now teem with sunken, baroque flourishes. The poisoned air has additional texture, shaping the light in nasty, unquantifiable ways, while sound travels differently depending on the intervening objects and materials. But the changes aren't just about ambience.

There are new rooms tucked in amongst the old layouts - add-on chambers for a handful of side missions that deepen the fates of certain characters, including Dr Mercer and his awful Hunter. Some areas and their tasks have been totally transformed: the original game's mounted-gun asteroid blasting sequence now sees you zipping around in zero-G (the remaster borrows Dead Space 2's more user-friendly jetpack), synching the ship's cannons to your weapons while boulders rain down on the hull. The annoying boss battles are back, yellow-painted weakpoints and all, but there's a sprinkling of worthwhile new puzzle variables, such as circuit-breaker panels which invite you to choose between, say, switching off the oxygen or the lights in order to power another system.

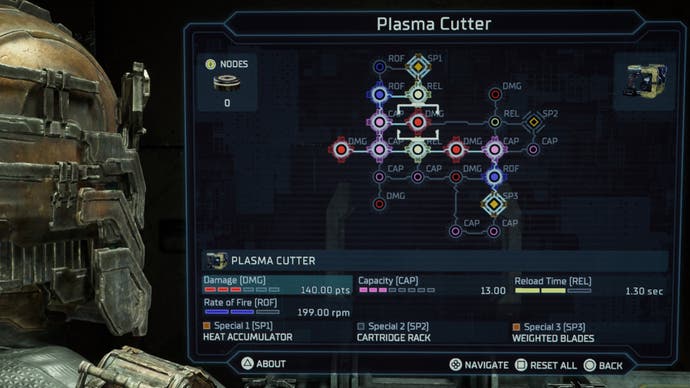

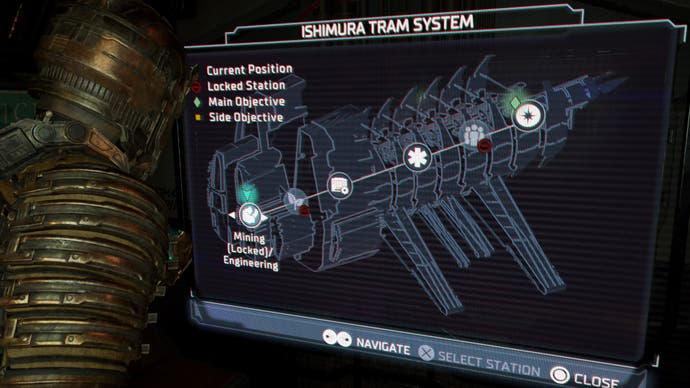

Some rooms or storage containers now require you to have a certain security level, which increases at story-triggered intervals - an incentive to revisit cleared areas using the redesigned tram system, which is no longer a chapter-ending device but more of a level-select hub, with main and side objectives flagged on the tube map. I found this irritating at first - the last thing I want in a remake is additional, gated looting for the sake of it. But both the security level promotions and the new side missions actually fit the game's back-and-forth campaign structure, ensuring that you'll always have something to investigate and unlock when you loop back through an area. Only a handful ask you to go off-piste, and the farther-flung optional chambers house new, nice-to-have mods for the game's modestly redesigned arsenal - a combo amplifier for your Plasma Cutter, or an extra ricochet for the sawblade-launching Ripper.

It all adds up to a comprehensive, if not essential-feeling rework of a cherished setting and playspace - nowhere near as ambitious as the Final Fantasy 7 remake's Midgar, but a step beyond a cosmetic touch-up. Where this year's remake loses me a bit is in its handling of Clarke and the backstory writing. One of the most significant additions is also a removal: giving Isaac Clarke a voice means taking away his voicelessness. No, I'm not trying to wind you up with semantics. Clarke's wordlessness in the 2008 game isn't simply a lack, waiting to be rectified 15 years later. It's fundamental to the horror and your understanding of the protagonist. Doing away with it produces a different, and perhaps, more comfortable experience.

To start with, Clarke not having a voice meant that you paid more attention to his wonderfully animated and expressive body - my favourite Dead Space feature after the game's legendary holographic UI design. It's all in the way his weight shifts when he strafes, the wobble of his shoulders when his health runs low, the relatable tilt of his head as he peers up desperately at yet another screenful of warning messages. The remake softens this: Clarke's injury fatigue is less visible, the animations less demonstrative. Instead, you pick up on his state via the new context-sensitive audio design, with different voice performances to reflect pain and shortness of breath.

Clarke's wordlessness made me feel more protective of him, back in the day, like I was guiding a shy child through a labyrinth. But it also, of course, makes him strange, his thoughts on the situation inaccessible, his very reality as a person in question next to the speaking members of the cast. Mute protagonists are often styled "blank tablets" for the player to project onto. 2008-era Clarke is more like a scuffed mirror. His motions follow yours, but there's something else in the reflection that eludes discovery. Having to perceive him primarily as a body also emphasises the body horror elements of his vacuum suit - beaten-down and contorted where, say, Master Chief's Mjolnir armour cuts and captures the light, with metal bands that look like flayed bones, a vulnerable glowing spine and a splintered visor suggestive of a man peering through the bars of a cell.

I'm not saying I've ever felt genuinely afraid of Clarke, but so much of the character's old charm is that element of uncertainty. For a man whose back is a literal health gauge, he is thrillingly ambiguous. The remake sacrifices this in order to make Clarke fit the more naturalistic voiced character he becomes in later games. He's an active participant in expanded, reshot dialogue scenes, joining in speculation about the origins of the Necro outbreak, offering his expertise rather than waiting for instructions, bonding with other characters like the botanist Elizabeth Cross, helping to flesh out their histories even as they flesh out his. He cracks the occasional joke. He still shuts up for long intervals when there's nobody on comms, mind you. He doesn't talk over environmental cues, or fill the void with gameplay hints masquerading as quippy notes-to-self. But he's a character rather than a stranger, and the story's obvious hero - the middle line between the bull-headedness of your mission commander Hammond and the back-biting of Daniels, your computer specialist.

All this absolutely has its advantages. In particular, developing Isaac as a voiced part also means developing the character of Nicole Brennan, his missing girlfriend and the Ishimura's medical officer. While she's still basically a damsel in distress, the remaster's side missions introduce a found-document backstory, both giving Brennan more agency as a character and digging into the reasons she and Clarke begin the game solar systems apart. But it all comes at the cost of eeriness - and moreover, it overlooks the other way of framing Clarke's original lack of a speaking role, which is that the events of Dead Space are sort of above his pay grade.

He's the greaser sent downstairs to fix the plumbing while the officers and top geeks discuss the plot. He isn't a practised soldier or leader, like Hammond - he doesn't even have a weapon, when you first set foot on the Ishimura - nor is his 2008 incarnation gifted with special insight on Dead Space's wider power struggle between governments, corporations and Scientology-esque cults. He's just a guy who's very good at taking things apart and putting them back together, and it turns out this is exactly what the situation demands.

The trick to fighting Necromorphs - which come in a range of excitable manifestations, from guillotine-armed skirmishers to pouncing leopardlikes and dart-throwing zombie infants - is that they can't generally be overwhelmed with sheer firepower. Instead, they must be disassembled, preferably after being dolloped in Stasis energy, so you can take your time aiming. The game admittedly departs from this idea a bit as the plot unfolds, with scavenged tools like the flamethrower and Force Gun allowing you to firewall mobs and shatter ambushers without much science, but dismemberment remains the guiding principle, not least because it's economical: ripped-off Necro limbs can be hurled with telekinesis in place of ammunition.

The remaster leaves all this essentially the same, save for a touch of re-tuning: the Contact Beam, for example, now has a continuous fire that makes it more practical against rank-and-file undead. It also keeps to the old rhythm of ambushes and enemy grand-standing, with Necros sometimes bursting through vents behind you and sometimes lurching around distant corners to waggle their joints whimsically while you absent-mindedly Force-lift a can of explosive fuel. Sometimes you're cool and precise, delimbing a Necro in the minimum possible moves while advancing to distance yourself from the second attacker you know is coming up behind you - all in a day's work. Sometimes, it's the kitchen fight from Dog Soldiers: flailing indiscriminately at walls of teeth and claws, stamping frenziedly on de-legged opponents, and wasting precious ammo on ragdoll animations misread as attacks.

All this ties back to the old Clarke's lack of a speaking role. His primary means of characterising himself wasn't through killing but these acts of violent, but careful re-engineering - a succinct articulation of his place in the world and the role he plays with regard to its various sprawling schemes and sinister machinations, human and otherwise. In particular, the emphasis on dismantling, rather than merely destroying opponents is a rebuke to the claims made by other characters that the Necros are a means of spiritual rebirth, transcending the constraints of individual human bodies. Each Necro you slay is a microcosmic shattering of those delusions: no, these are not angels of the rapture. They are arms and legs and torsos and heads. If they appear otherwise, that is because they have been incorrectly put together. It falls to Clarke to reduce these creatures to the sum of their squirming parts.

Again, shifting Clarke's characterisation to dialogue can't help but spoil this, whatever the competency of the dialogue writing and Gunner Wright's sturdy voice performance. The character's actions no longer speak louder than words, and I think that's symptomatic of the Dead Space remake as a whole. While this is a meticulous and appreciative reworking, a little too much of it seems designed to get in the original's way, to blur its focus and mutate it into an appendage of the omnivorous franchise operation it would become, where everything needs to be written into an on-going narrative backdrop, and genuine ambiguity is minimised. Rather than rescuing the past, it represents a franchise reaching its tendrils backward through time to become its own progenitor. The results can be compelling, but make sure you play the 2008 game first.