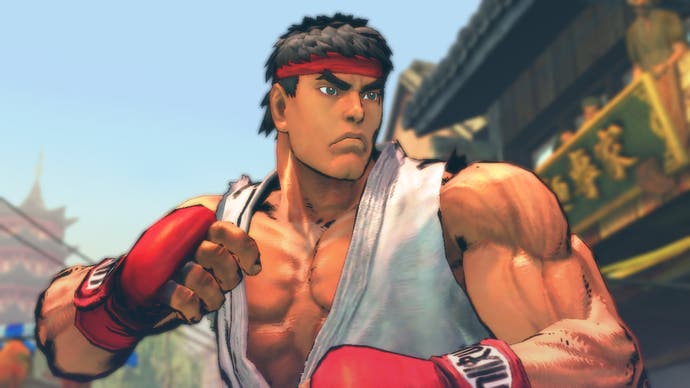

Daigo Umehara: The King of Fighters

The Street Fighter world champion speaks.

"Right now, there's nobody younger than me that I feel threatened by. I haven't met anyone that I felt possesses the skill to surpass me in the future. I'm not over-evaluating myself. I can analytically see their weakness, their ineptitudes."

Daigo Umehara is better at Street Fighter than you and he knows it. Fighting games always bring out the inner show-off, but his is no hollow boast. Earlier this year, the 28-year-old Japanese defeated American champion Justin Wong at the Evolution 2009 Championship to take the Street Fighter IV world title.

Daigo Umehara, it turns out, is better than everyone at Street Fighter.

This victory was just the latest in a long line of high-profile competitive achievements that Umehara (Ume, to his friends) has to his name, the most famous of which is his astonishing comeback against Wong during the 2004 Evolution loser's bracket final. You don't need to understand the intricacies of Street Fighter III's parry system to appreciate that something extraordinary is happening as he bats away each of Wong's potentially lethal attacks before taking the round with a dazzling special move of his own. The crowd's ecstatic reaction, coupled with Umehara's understated demeanour in the face of such deafening adulation, catapulted the clip to YouTube stardom, where it ranks amongst gaming's most famous.

Since then, Umehara's fame and reputation has spread through the fighting game community and beyond. He plays with unrivalled precision and grace, combining the reactions of a peak-form Muhammad Ali with the strategy of a Garry Kasparov. He is undoubtedly the greatest Street Fighter player to have played the game.

But his own understanding of his supremacy comes not from the vanity of world championship titles but rather from the measured perception of a giant. "I think, right now, I may well be at my absolute peak," he tells me. "My reactions are probably comparable to when I was younger, but I no longer grow agitated when I'm cornered. Nothing can mentally break me anymore; I have mastered nervousness and tension. I can instantly tell opponents apart and categorise them into groups and types according to their personality and weaknesses. As I haven't felt my physical abilities weakening yet, I think I might be at the peak of my career as a fighting gamer."

Spoken by anyone else, this might come across as supreme arrogance. But while Umehara's known to his fans as "The Beast" (a term he neither coined nor uses himself), his real-life persona ill-fits the nickname. This tall, handsome Japanese is altogether shy and unassuming. In contrast to his American rivals, Umehara shuns the spotlight, rarely giving interviews to the press or meeting fans.

He is a star born in the arcade scene, a dimly lit underground world filled with cigarette butts, bleeping neon lights, cathode-tan boys and the sweat of twitch competition. His digital sport has neither the glamour of boxing nor the ceremony of wrestling: there are no promoters or agents to turn talent into stars in this world. Even if there were, one feels as if Umehara's well-mannered, nice-boy exterior would always mask the inner beast.

Umehara is near-impossible to track down. Initially, Capcom suggests I fly to Tokyo, find an arcade where he's playing of an afternoon and sit next to him with a tape recorder. After he declines an invitation to a UK tournament and fails to show up to a meeting we schedule during this year's Tokyo Game Show, Capcom steps in to help organise a cross-continental rendezvous, using one of Umehara's bilingual friends as an intermediary, to put my questions to him.

His reluctance to talk to interviewers coupled with these difficult-to-reach circumstances have contributed to the enigmatic legend that is Umehara. Rumour and speculation follow his every move. When, in 2005, he took a two-year break from the fighting game scene, some fans speculated it was so he could focus his attention on his other love: pachinko. His reactions, so the story goes, are so supernaturally fast that he is able to tilt the odds in his favour far enough to earn a living from what is essentially a game of chance. In truth, Umehara works in the public welfare/health sector by day, following in the footsteps of his parents who both work at a hospital in Aomori, Japan.

"Playing games professionally is not really an option in Japan," he explains. "If I did really want to do something with my gaming skills in the industry, I think I would have already done so by now. It's only relatively recently that I started to receive invitations to overseas tournaments with prize money. In Japan, games are something you play for enjoyment; you don't expect anything in return."