Can the Clone War Ever Be Won?

A clamour of clones.

We all know the clones. And often, we welcome them. After all, you can't play Blizzard's World of Warcraft on a phone, so Gameloft's Order and Chaos seems like it fills a hole and doesn't hurt anyone. Cloning isn't new, either. From Pong, probably the most copied game on the planet and allegedly a copy itself, to Breakout, success has always bred various degrees of imitation.

Cloning is a history full of strands - character mascots, the fascinating story of Tetris and the ranks of imitators birthed by any popular title. But over the last year, clones have multiplied to what feels like saturation point. They're bigger business than ever before - a business that, in some ways, is a guarantee of profit.

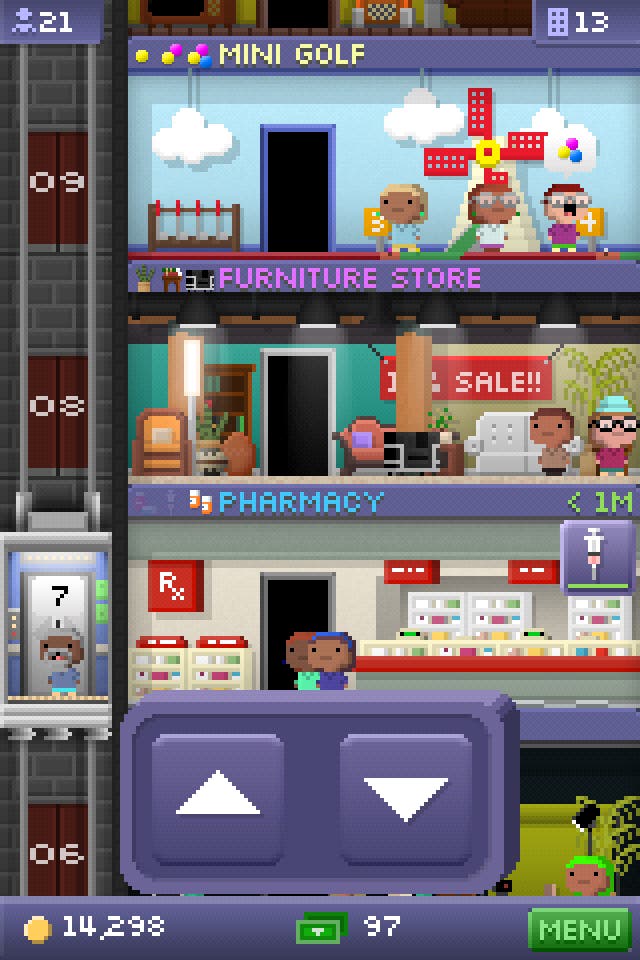

At the moment everything is focused on Zynga, an enormous company built in large part through copying popular games, and last week Nimblebit, developers of Apple's 2011 Game of the Year Tiny Tower, released this image. It spoke a thousand words, though it can be whittled down to two: "thieving bastards." Zynga tried to acquire Nimblebit first and, after being rebuffed, simply hunkered down and copied Tiny Tower instead - producing the remarkably familiar Dream Heights.

The last fortnight has shown what a prevalent problem this is, with Triple Town developers Spry Fox launching legal action against developer 6waves Lolapps and its game Yeti Town. On the same day, there was another accusation against Zynga - Canadian developer Buffalo produced its own image about Zynga ripping off its game Bingo Blitz. Apparently it's the most popular bingo game on Facebook, which brings to mind gigantic dollar symbols.

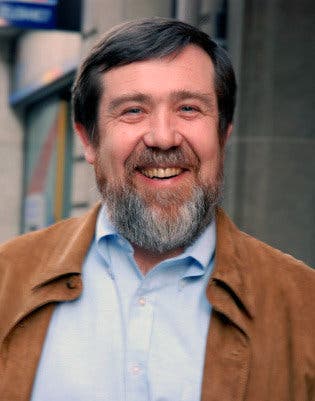

I contacted Zynga for this article, and was disappointed not to receive a reply. But CEO Mark Pincus did send an internal email around that Venturebeat got a hold of. A child could take apart his arguments, not least because he clearly hasn't played the games he's referencing, and let's not forget this is a man alleged to have shouted in a meeting "I don't f***ing want innovation, you're not smarter than your competitor. Just copy what they do and do it until you get their numbers." It's certainly getting to something when Forbes is publishing these kind of sentiments: "Zynga is a creatively, and I would argue morally, bankrupt company, and the sooner investors realize this, the faster they can fade from prominence." Yowza. As for Nimblebit, the developer declined to comment further, and pointed back towards last week's image.

These are strange times. As recently as December 2011, Zynga settled a lawsuit in which they accused Vostu Games of cloning Zynga's games, receiving a fat cheque and changes to Vostu's software. If you've got enough brass neck you can get away with this kind of thing. But Zynga is just a symptom. Directly cloning games is an industry cancer, one that adapts and evolves as it's confronted - take Hasbro, who owned the rights to Scrabble, and its suing of RJ Software, the maker of Scrabble clone Scrabulous.

Big company with a strong claim for copyright infringement versus a blatant clone on Facebook - you'd think that might be a shoe-in. Instead the lawsuit started in January 2008 and dragged on, with Facebook dithering before eventually pulling Scrabulous in July that year. By December 2008 Hasbro had dropped the suit. Why? It couldn't pursue it any further. Not only had the high court ruled that the game Scrabble couldn't be copyrighted, but RJ Software had since changed its game's name to Lexulous, pushed some score tiles around the board and made sure you started with 8 tiles instead of 7. The derisory nature of this outcome is underlined by the fact that users' Scrabulous accounts carried over to Lexulous. Oh, and the original Scrabble rules were quietly reinserted last year.

A game like Scrabble is one thing. But more and more often, the stories are about small developers making a game that either gets cloned instantly or is beaten to market by its copies. This is not a matter of iterative design. The current situation with clones is that what was once a niche segment of the games industry - more akin to counterfeit t-shirts than B-movies - is now, thanks to quicker turnarounds and more direct sales channels, selling the products of others at unprecedented volume. Though clones have always been a part of the industry, it is foolish to think that makes them benign. The opposite is true: they flourish like weeds, and remain largely unchecked.

The industry is cautious about engaging the problem head-on, because it's a real can of worms - in fact, the history of gaming litigation throws up countless examples where companies have settled at the last second for fear of creating precedent.

QCF Design is responsible for the excellent Desktop Dungeons, a game that was cloned in late 2010. One of the studio's frustrations wasn't just the lack of lawyers that could navigate international copyright claims, but the laws themselves. "Copyright wasn't invented to cover game content," says QCF's Danny Day. "We need new ways to protect the obvious investment that goes into creating a new or novel system of interactions in a game."

That's a simple truth - copyright law as it stands does not contain adequate protections for some of the most important characteristics of videogames. Any changes will take years, possibly decades, and defining where iteration ends and copyright infringement begins is always going to be extremely difficult. But the alternative is here and now on your smartphone, where game designs can be copied, in some cases within weeks, and released before the original. And, as Day points out, "A lot of the current debate around the topic is muddied by the same tedious and easily-argued statements from people with very little skin in the game."

Has Nimblebit copyrighted Tiny Tower? Perhaps it has, and the simple fact is that copyright as it is currently defined isn't protecting them adequately. The prospect of a costly and lengthy legal battle against a company with Zynga's resources is unappealing, and a cynical observer may say a key plank in the company's strategy.

If Nimblebit has decided that putting everything on the line to take on Zynga is too much, who can blame it? It's a thankless situation: lose-lose for Nimblebit, and win-win for Pincus. No-one could tell you how many clones have been published in the last few years, but the number is too many. Super Mega Worm and Death Worm. Farmville and Farm Town, Halo and Nova. Lay The Egg(!), Scrabulous, Muffin Knight, Ninja Fishing, Dream Heights, Modern Combat, Fortresscraft. Pile 'em high, sell 'em cheap.

Copyright isn't going to change anytime soon, and there will always be cloning going on. The industry's attitude is reactive - when something like Dream Heights happens, we're never short of articles and stories about how awful it all is, and how evil Zynga is. Then it all goes quiet and we wait for the next one, and for the cycle to start over.

The games industry as a whole should be more concerned about clones as a phenomenon, and not just their own back garden. "It's basically the STD of the industry," says Danny Day. "You don't really believe it'll happen to you, so few people take the right precautions." Trade bodies have a responsibility to educate their members about exactly this kind of risk, but as it stands they do not do enough - an imperfect legal system can still serve a purpose.

The International Games Developers Association last published a white paper on IP protection in 2003. That's a year before Facebook launched and four years before the first iPhone. Its Business and Legal Issues page links to an intellectual property wiki that doesn't exist.

Back at home, the UK's two major trade bodies are equally behind the times: The Association for UK Interactive Entertainment (UKIE) interprets its IP protection responsibilities as involving pirates and dodgy market traders. As for Tiga all I've ever known them to do is lobby for tax breaks. Tiga's stated purpose is "to make the UK the best place in the world to do games business," and Games Tax Relief is obviously very important to a certain segment of the industry, so fair enough. But it's worth remembering that Tiga was initially founded to help independent studios.

There is assistance available to small UK developers from these bodies, but it's things like networking events, introductions to publishers, and tool discounts. But indie developers don't need a careers fair. Small studios and startups need money, and the next best thing is a trade body that offers practical help with those corners it's tempting to cut - such as, for example, legal advice on protecting IP. It's a role neither UKIE or Tiga show any interest in fulfilling.

Cloning is a massive issue for gaming now, and if an equivalent phenomenon was seen in movies or music there would be a taskforce dedicated to protecting the IP of small British developers, announced by David Cameron while alluding to their "bulldog spirit."

Back in the real world, developers must educate themselves - and often learn through bitter experience the hard realities of creation in a sea full of sharks like Pincus and many smaller, no less deadly bottom feeders. Fighting the cloners is not a war that can ever be 'won'. But it's a battle worth fighting regardless, one where original work can be protected better, and one where developers must demand better unions than they currently have. This should be a war fought on a thousand fronts. The alternative is to watch companies like Zynga flourish, and to do nothing.