Bomb Rush Cyberfunk review - one of gaming's purest joys returns in this almost-sequel

Birthday cake.

Early on in A Burglar's Guide to the City, Geoff Manaugh's transporting and transformative book on the criminal uses of urban space, I met Bill Mason. Mason is a jewel thief, yes, but also a "watcher of buildings". He's pretty much a reader of buildings.

Mason started out in real estate, and became intrigued by the apartments he was showing clients. "I liked buildings," he told CNN's Wolf Blitzer in 2005. Why does he like them? Because, "you could go in and achieve something, bypass a lot of security. And it was a game, it became a challenge, a sort of adrenalin rush I got addicted to." Mason became a jewel thief, in other words, because of something that sounds a lot like a form of love.

A reader of buildings! Mason would wander, often at night, reading the faces of the buildings he passed. He was looking for useful ledges, easy windows, rooftops he could reach at a push. It was a process of finding useful details, and then chaining them together to create a path. I know this feeling. I was doing it last week.

Millennium Square, New Amsterdam, in the pitiless mid-day sun. Sega blue skies overhead and bleached, scorching concrete, but I've been asked to tag a billboard on the side of a tower that looms high above me. Too high? I need to tag this billboard to move on, but I've been circling the building for hours, and I can't work out how to get onto the first floor, let alone the fifth.

But maybe, as Mason would suggest, I'm starting with the wrong building. I'm starting with the target. What's nearby? A run of low offices, suspended over an entrance to the square itself. No good on one side, but on the other I see an interrupted series of railings that I could probably skate across. Where do they lead? What leads to them in the first place? And working back, how do I find a way to that?

This is Bomb Rush Cyberfunk, then, in which the city is a playground, but also a puzzle, a sequence of moves and possibilities waiting to be excavated, to be strung together. I love this stuff, and I also remember it well. Because Bomb Rush Cyberfunk is also Jet Set Radio, a game that came out long before Bill Mason ever sat down with Wolf Blitzer. A game that was a colourful, sweet-natured blast of noise and movement straight from the Y2K aesthetic. Jet Set Radio and its sequel, Jet Set Radio Future, both known in Japan as Jet Grind Radio, are proper classics. You travelled around busy streets on rollerskates avoiding security forces and tagging graffiti to take back the turf. These were games about the pleasure of moving through space in hops and loops and grinds, but those pleasures gave way to deeper delights, too, as you learned to understand the place. You learned, as Bill Mason might agree, to love it.

I always loved Future more than the first game, because it had bigger, more complex maps, and it took away the timers for each level, switching out challenge in favour of immersion. And I spent hours in this peerless hymn to movement standing very still, parked on a street corner, looking up, trying to work backwards from the spot I wanted to reach through a tangle of billboards to ride off, cables to grind, platforms to land on before spinning, destroying momentum, and then tippy-toeing onwards. I would sketch each journey in my mind like this, before painting over it with the actual movement.

Not surprising really that I find myself doing the same thing in Bomb Rush, because Bomb Rush is an almost-sequel to an astonishing degree. Tokyo-To is switched out for New Amsterdam and a fight against an evil corporation has been replaced with a mystery regarding a missing head, but the game feels the same to an almost spooky extent. It's not a clone, because Team Reptile isn't hoping that you've never heard of Jet Set Radio. They're absolutely hoping that you love it, and you miss it, and you want more of it. I suspect they made this game primarily because for the last twenty years, Sega hasn't made it.

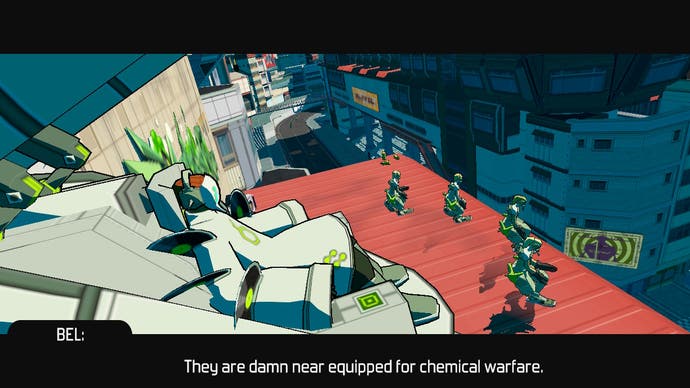

As such what I got from Bomb Rush was an endless series of deja vu moments as I played. There's the big stuff - the chunky-footed character designs of the skaters, the Cel-shaded streets where you send pedestrians scattering, the trick system that challenges you to work up wild combos as you grind and skate from A to B, that gorgeous, intoxicating sense of movement which makes you feel, regardless of the surface, that you're moving over glass, over a frozen lake.

But most arresting to me was the small stuff. Jet Set Radio Future had a weird quirk when it rendered underfoot grating: looking ahead, the tiny bars of metal got so thin they looked like they weren't there at all, like you were skating into the abyss. Bomb Rush Cyberfunk renders grating the same way. Then there's the two-beat laugh of Gum, my favourite Jet Set skater, which I hear again and again from Bel, one of the new team. There are the sun-worn buildings with their leaning billboards advertising sheer enthusiasm as much as any specific product. There's the soundtrack, which comes in part from the great Hideki Naganuma who worked on Jet Set. It's a perfect follow-up, not just because of the scratchy, shrieking, noodling richness of it as you move from house to funk to a spectrum of bright, indescribable micro-genres, but because of the way that the songs loops and scatter and occasionally snag, at the same moment as I snag on a particularly challenging puzzle, and I have to then spend ten minutes jumping into space and missing a connection with the same chorus repeating and repeating.

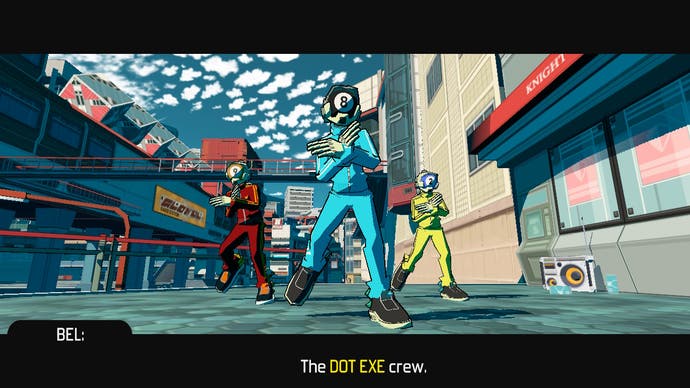

It was disconcerting at first, all of this. I think I knew Bomb Rush would ape the controls of Jet Set Radio - the way you move around a world built of grind rails and half-pipes, nursing that combo with tricks. I knew it would take the structure, as you move from one neighborhood to another, first painting over a rival gang's graffiti and then taking them on in trick challenges to gain dominance. But all these littler things that made up the game, from moment to moment, all these elements that felt just so - it was like my own memories were being raided.

Then, of course, I realised the simpler truth - this game I love so much that it has been a primal influence over the last two decades, a lens for me through which almost all games are viewed? This game is a game that others love so much too. Bomb Rush Cyberfunk is hard to untangle at times: similar, too similar, not similar enough? But ultimately, it's one of the more explicit acts of love I have ever encountered.

And I'm probably saying this too late, but it's good, too. And it's mostly good in its maps, its neighbourhoods, which offer the Cel-shaded Jet Set look and urban density, while also providing a little more space than I'm used to. New Amsterdam is a city of squares and shopping malls, where you trick around the edges, and work your way higher - like Jet Set, Bomb Rush loves a good corkscrew - but then come back to the centre before setting off in a new direction. It has really complex platforming challenges, one of which is set inside a storm drain and is one of the most intricate pieces of movement I have ever encountered, but it tends to separate them, either by a loading screen or hiving them off as a post-street battle hallucination, where buildings and grind rails hover above a throbbing tie-dye void and you have to pull off really improbable chains of stunts to progress.

I think I prefer the organic sprawl of Jet Set, but I also understand that Jet Set was building on a real place, whereas Bomb Rush is building on memories of a fictional place built on a real place. You can tell. The specifics are lacking, the awkward, stacked-up, real-world wriggliness of Jet Set has been dialed back a little. We are one more step removed. Crucially, though, these new spaces all offer a nice sense of place in their own right. There's a pyramid, away from the bustle of the city, that feels like one of the most isolated places I have ever been, while one of the later maps, my favourite, is a right-angle of streets in the dead of night, with towers racing up into the sky overhead and disappearing down into the mists below. There are missions here - have to hit those tags and win over the local team - but there's also time, amidst the chaining of movement to just exist. It's the poetry of space revealed in the gaps between the action.

Another level down: it's also, again, one big reference. That night-time neighbourhood takes its cues from The Skyscraper District and Pharaoh Park, my favourite of all Jet Set Radio Future maps. Midnight urbanism and shopping, but also these weird golden statues that hint at mankind's ancient past. Sheer height creating a sense of isolation. Even when it's creating new places, Bomb Rush cannot leave Jet Set Radio behind - not even slightly. It doesn't try. It doesn't want to.

And this in turn is why the new stuff doesn't interrupt the nostalgic flow too much. It either doesn't matter, as is the case with the new plot, the fact that you can ride bikes and skateboards, that you can take off your wheels and just walk for a bit more precision, the fact that you can now fight enemies as well as simply spraying them. These are all nice additions, but I barely noticed them moment-to-moment. Or else it matters and it also improves things in a harmonious way. You can ride rails above you as well as below you now - that's cool, and I reckon Jet Set Radio would have gotten to it eventually. You can use a boost pack to give you a double-jump to get you onto tricky rails or pull you back from the brink: elegant and thoughtful! You can lean in when grinding corners and work up a multiplier, adding an extra dimension to the trick game.

Best of all is the new graffiti system, something the two Jet Set games could never decide on. Should it interrupt you or not? Should it require muscle memory, or would that just feel like busywork, like the actual opposite of creativity? Bomb Rush's solution is ideal. Tagging freezes you in space and gives you a series of nodes to connect with swipes of the thumb stick. The more graffiti designs you've collected on your travels, the more nodes light up, and as you swipe around in the moment, you're actually selecting your way through your artist's blackbook, zeroing in on one specific design from many. It makes art feel magical, like part of it is happening in your character's head and you don't get to see the process. It's like you have the canvas and all of these overlapping potentials, which you slowly whittle down to one. And going back to it now there's such flair in the handling too - the camera tilts with each swipe. The poses! The energy of it! The sweet fury! You're Jackson Pollock!

I have left stuff out, I know it, but that's a reference too. Part of the thrill of these games is that you're so busy, but you're also dreaming as you play, following the Valium haze over the city as rail connects with ledge connects with halfpipe. That haze! I will never forget the night I first discovered Jet Set Radio Future. I'd borrowed it from a friend and played it a bit one afternoon and assumed I wouldn't come back to it. But I fired it up again about ten, just before bed, and then I looked at the clock and it was three in the morning and I was racing over the back of a pink neon dragon looking for one last tagging spot. Reader, I was gone.

I lost time in there, and I've lost time in Bomb Rush Cyberfunk too. But it's a subtly different kind of time, perhaps. This is a game about rediscovery, about remembering, about seeing things again that you had almost forgotten. Deja vu! It has the thrill of the earlier Jet Set games, but now I've finished the whole thing I can see it's more than that - and only because, paradoxically, this game is always careful to be less than its influences too. It has to be less - that's the point, the glory of it. Selflessly, it points the way back towards a gaming experience that was unprecedented. It's a picture frame, the perfect bit of hanging and staging in a gallery. Its rich, energetic imagination is mainly spent on recreation and refinement.

To put it another way, it's an act of love, and when that comes to art, the thing that is actually loved in the first place has to retain all the glory.