Qrth-Phyl and rethinking how we remember video games

Mental blockade.

Game preservation is one of those topics that we keep returning to with greater and greater frequency. In a week like this, and a year like this, it's not hard to see why. Marvel's Avengers, a mega-budget game that still feels relatively fresh, is being delisted, while Hyenas, which looked weird and rather brilliant, has been cancelled before it's even been released. It's heartbreaking, and my thoughts go out to everyone affected. People are losing their jobs and others are seeing their work forgotten. There's also a sense we're going to see more of this and more often. Hollywood is making movies that people will never see and TV shows that people will never binge, while brilliant people are giving huge and valuable chunks of their lives to make games that people will never play. It's terrible stuff.

The question of game preservation should rightly seem small compared to people losing jobs, but while the news has been so bad these past months there have also been a number of game releases which highlight different ways absent games, at least, might live on in memory. It's doubly hard, I think, to preserve games like Marvel's Avengers or Hyenas: games which are always online, multiplayer, social affairs which require servers and deep communities of players to make sense. But game preservation is tricky stuff even with older single-player offline games. Maybe this is why there are so many signs of changes to how people are thinking about game preservation. So many people are asking: what does it mean to preserve a game or at least preserve its memory? This stuff is in flux.

I wrote about this a few weeks back, when I had the good fortune to play The Making of Karateka and Bomb Rush Cyberfunk in the same week. Very different games, these, but both are united by being deep and thoughtful acts of memory. Bomb Rush Cyberfunk is a spiritual successor, an act of digital reanimation, to a beloved game series that has been away from TV screens for the best part of two decades. Its slight spookiness is part of the fun: it's someone else's ideas but brought back by a new team and powered by sheer love of the games of the past.

Karateka, meanwhile, is a self-conscious effort to establish a kind of Criterion standard for video games. It takes a beloved and influential old game, Jordan Mechner's Karateka, and tells the story of its creation while also pulling at all the threads that make it special. It also includes a handful of versions of the games to actually play, alongside playable demos and vignettes and games that were part of the Karateka story. It's utterly wonderful, and also rather moving.

This week, though, I was delighted to get an email from a creator I hadn't spoken to in an absolute age. Back at the start of Xbox Live Indie Games, I was swept away by the work of Matt Verran (Hermitgames), a developer that made itchy, flickering arcade treats out of shards of light and a deep understanding of the glory days of the arcades. One of the last things of Verran's I played was Qrth-Phyl, and this week Verran emailed me to tell me that the game was now on Switch.

I've been playing it all week and it's just a delight - as fresh and unprecedented now as it was when I first played it on the Xbox 360. And the preservation of memory is right at the centre of this project. Qrth-Phyl is all about bringing an old game and an old game's history to life - but in a way that's quite different to the approaches taken by either Bomb Rush Cyberfunk and Karateka.

Qrth-Phyl is a hymn to Blockade, the arcade game from the '70s which is probably much better known as Snake. You know, the old phone charmer in which you control a little line of pixels that gobbles up dots and slowly grows in length, wrapping around the screen until you eventually crash into your own body. Snake is one of those persistent lucid dreams of games - it came back a few years ago in the form of a game about traffic, while there's a really successful multiplayer clone on smartphones that probably makes gajillions each month. I was once at a Microsoft developer conference in Warwick University and a computer scientist lecturer explained that the first year project for his students was to make their own version of this design. It isn't going anywhere.

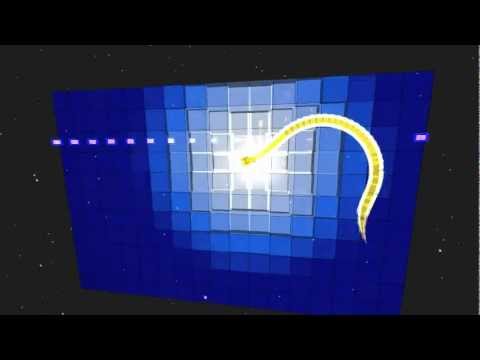

It really isn't, but Blockade itself has been forgotten, I think, and Qrth-Phyl is an attempt to change that. And it takes a fascinating path. Rather than offering a version of the original game or a painstaking remake, Qrth-Phyl takes the basic Blockade idea of a snake that gets longer the more it eats and throws it into three dimensions, offering the shimmering, slatey layers of light that Verran is known for and creating something colourful and kinetic that still feels like a marvel that just got made.

In Qrth-Phyl you pilot your snake around the outside of a 3D shape, and then intermittently pass inside the shape to move through the air itself. There's generative design to the challenge, which means you never know what kind of challenges you're going to face or what order you'll face them in, and it's a score-chaser at heart, with the game carefully tracking each dot you consume as you play.

If this was it, it would be brilliant. But hidden within this is a sort of digital museum that tells the history of Blockade and the idea it gave to game worlds. Genetics is very much the guiding principle here - the way that ideas travel and evolve over time. Uncover the museum sections - I won't give away the manner in which they're hidden - and your snake becomes a green-scale strand of DNA moving between historical moments. Here's the creation of Blockade and its first appearance at a trade show. Here's the rush to a market that was already filled with pre-emptive clones. Here's the story of how it got onto mobile phones. Here's the connection with the lightcycles of Tron.

What I love about this is that it's a game's history filtered through a very specific design approach. It's Blockade as one creator remembers, loves, and is influenced by it. Blockade is everywhere in this game, even though you can't really play the original Blockade by playing it.

That, in a way, is memory, which brings us very near to a beloved thing but also throws up a barrier. Memories are sharp because they take us this close and then say: no further. And Qrth-Phyl is a game that understands this utterly.