Saturday Soapbox: A Shoots, B Kerns

Why a game about type-setting might be good news for everybody

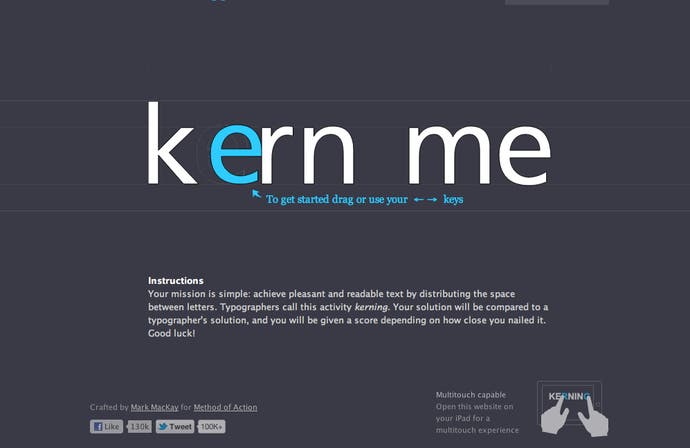

Have you played Kern Type? It's a game about kerning. I had no idea that kerning actually existed until I came across this stylish little browser oddity a few months back. Now I'm a bit of an enthusiast.

Kerning - and I'll admit that I'm still not entirely clear on this - seems to be the name given to the science or art of spacing out the letters in a piece of text so that your eyeballs don't explode in horror when you look at it. Basic legibility comes into this somewhere, but it's mainly about pure visual pleasure, I reckon. It's an aesthetic indulgence, and - along with Post-it notes, Hollandaise sauce and Frasier - it's the kind of thing that only a truly civilised world would have created.

I gather that Kern Type has some kind of link to education, but it's also brilliant fun in its own right. Everyone I've shown the game to has completed it, and most people replay it until they've nailed a perfect score. It's not that Kern Type magically turns kerning into something playful, though. It's that kerning is inherently playful anyway. Kerning already has the chops to be a game, and Kern Type just frames the whole business correctly.

As you've probably noticed, this sort of thing seems to have caught on over the last few years: video games that look beyond the worlds of futuristic military hardware, extreme sports, or cute anthropomorphic monkeys for their inspiration. On iOS or Android, for instance, you can find games about being a space pirate, but you can also find games about parallel parking or putting things in the bin. These odd sorts of offerings have always been around, but now they're legion. The industry's gene pool is expanding in some unusual ways. Why is this? What's happened?

I instinctively trace a lot of this stuff back to WarioWare, the first game that ever allowed me to catch toast for the hell of it, or hold a dog's paws to make it happy. Maybe it was Shenmue, actually, with its day jobs and forklifts, or Sim City, with its quarterly financials. Many of these sorts of games - well, okay, maybe not WarioWare so much - seem to capitalise on what William Goldman, in one of his excellent books on scriptwriting, called "how to" sequences.

Film audiences, Goldman noted, love learning about things - and it barely matters what those things actually are. If you can offer a slight insight into how people go about doing something fairly precise and specialised - be it milking a cow or robbing a bank, or even robbing a bank while riding a cow that you've just milked - movie-goers lean forward, eyes glittering, and take note. It doesn't even have to be a realistic insight you're providing. It doesn't even have to be true.

I think all audiences like this sort of thing: we like rules and restrictions and a glimpse at the inner workings of something quite niche, even if it's also fairly mundane. Now that there are low cost ways to make games - and that often means low risk ways to make games, too - designers are really getting the chance to capitalise on this. Games about kerning, games about stitching, games about making trains run on time: the pixies and elves and space marines are still hogging a lot of the limelight, but it's perhaps not so surprising that it's steadily getting a little more diverse out there.

There's also the fact that designers and audiences have been growing up together. A lot of us are well into our mid-thirties or beyond now, entering the period in life when you first find yourself thinking about keeping bees, say, or researching the best place to buy a really good rock polisher. We're all getting new hobbies and rekindling old interests, and perhaps the games we're playing reflect that.

And also, of course, there are a just a lot more people who you could class as gamers these days, and they make us considerably more diverse. The last time game designs were spread across such a broad range of subject matter was probably the days of the arcades, in fact - and that also happens to be a time when everyone from Martin Amis to my dear old grandparents were shovelling coins into gaudy cabinets and discussing the best way of keeping Mikey alive in the Brain levels of Robotron. Back then there were games about serving root beer, and games about delivering newspapers. Why wouldn't there be, given the massive, richly differentiated audience? Nintendo even made a game about operating a vacuum cleaner. Apparently, it wasn't bad.

I should probably point out here that I'm not trying to get you excited about gamification all over again. Games drawing their influences from the abnormally normal parts of life does not have to equate to gamification at all, in fact.

Gamification is completely the opposite, actually: it takes the boring things that you hate doing - the really helpless cases, like sorting through masses of tedious scientific data, perhaps, or doing push-ups - and uses extrinsic gaming devices to trick you into grinding away at them anyway. A classic example of this is something like Chore Wars, in which people tidy their houses because they get to award themselves imaginary points afterwards. As smarter people than me have noted, this is bribery rather than game design - even if you're only paying yourself with nothing more substantial than make-believe pennies.

Kern Type gives you a rating at the end, then, but it's there to genuinely grade how well you performed, rather than to lure you into playing the next level and the one after that. It's the noble scoring system of Defender or Pac-Man, rather than the meaningless accrued XP of some iOS app that tracks how often you recycle plastic. If this weird little kern-'em-up's part of a trend, in other words, it's one that's all about ignoring extrinsic lures and enjoying the intrinsic appeal of everyday things instead. It's about making the most of the aspects of your life that are already fun.