Without Dungeons & Dragons, Fighting Fantasy might never have existed

Ian Livingstone and Steve Jackson on writing a phenomenon.

What do you think of when you hear the words "Fighting Fantasy"? Do you remember being absorbed for hours as a child, hurriedly flipping pages and rolling dice, hoping you'd chosen the right path? Perhaps you talked about it with friends in the schoolyard, swapping strategies, comparing notes. You almost certainly remembered the deaths.

Whatever you remember of it, the effect the books had is undeniable. More than 20 million copies have been sold, making writers Ian Livingstone and Steve Jackson best-selling authors, in addition to all of the other plaudits they've received. In fact, few people are as decorated in the games industry.

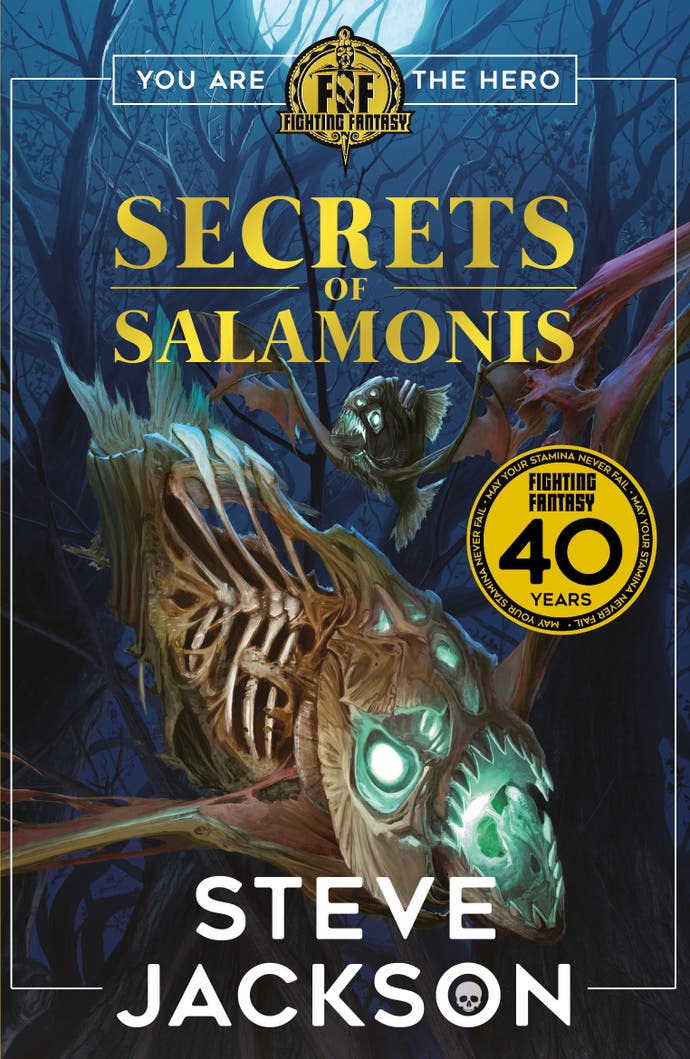

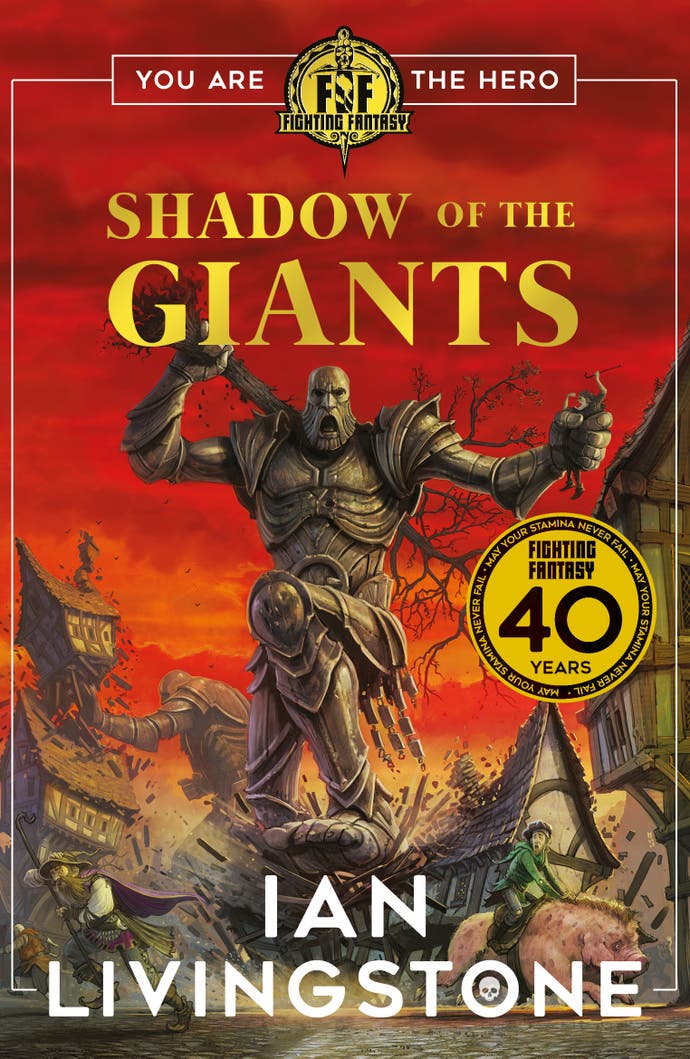

And this year, Fighting Fantasy turns 40 years old, just like me. And in celebration, two new books are being released: Shadow of the Giants, by Livingstone, and Secrets of Salamonis, by Jackson. And they're coming out today - Thursday, 1st September.

But the story of Fighting Fantasy begins more than 40 years ago, as I discover talking to Ian Livingstone and Steve Jackson in episode 21 of the One-to-One podcast. And it begins with a game we all know today but that was unheard of at the time: Dungeons & Dragons.

More specifically, it begins with a letter from the co-creator of Dungeons & Dragons, Gary Gygax, who, in 1975, somehow finds himself reading a newsletter written by Livingstone and Jackson, and their flatmate John Peake, about board gaming. And Gygax likes it so much he wants to send them a copy of his freshly made game to see what they think.

Which might not sound remarkable, but Gary Gygax was in America, whereas Livingstone, Jackson and Peake were in London. And that newsletter of theirs, Owl and Weasel, only 50 copies were made of it. And it was issue one. For one of them to somehow make their way onto Gary Gygax's desk is astonishing.

Livingstone, Jackson and Peake had been friends since school, since Altrincham Grammar School for Boys to be precise. They had bonded over a love of Lambretta scooters and, as would prove fateful for them, board games. But there weren't a lot of board games in 60s England to play: Monopoly, Buccaneer, Formula One and Cluedo were about it. And it was the search for something new that would fuel them.

Jump forward roughly a decade and the trio are back together again, after further education, sharing a poky flat in London and playing board games because they've got no money to go out and do anything else. And this time they're wondering, 'Wouldn't it be a great idea to somehow turn our hobby and passion of playing games into some sort of enterprise?'

This is where the idea for a newsletter comes from, and after a quick prototype, 50 copies of Owl and Weasel are printed, and Gygax finds himself holding one of them. Ian Livingstone recalls what happened next: "He wrote to us and said, 'Love your magazine. Here's a new game I invented - what do you think?'"

Just like that, Gygax sent them Dungeons & Dragons, making them among the first people in the world - certainly the UK - to play it. And predictably, they loved it. "Steve and I became obsessed," Livingstone says. "John [Peake] didn't like it at all, but we all agreed to buy as many copies as we could." They decided they'd sell them through their newsletter. But they couldn't afford much. "We ordered six copies - that's all the money we had in the world."

Still, this impressed Gygax. Perhaps he saw similarities in how the trio from London were operating a gaming business out of a flat as he was. Whatever it was, he liked them. So, "On the back of that order," Livingstone says, laughing, "Gary Gygax gave us an exclusive three-year distribution agreement for the whole of Europe."

So it would be that our London trio would introduce Dungeons & Dragons to the UK and Europe, and unsurprisingly, business boomed. And in the rush to formalise their operations, they created a company, and found inspiration for a name in John Peake's bedroom. "John's bedroom was like a workshop," says Livingstone. Peake was an engineer, a craftsman, making boards for games and other things. Livingston, then, means it literally. Games Workshop was born.

The problem was, people heard the name and thought it meant there was an actual shop and they could go to it. So they turned up and milled around in the street outside their flat looking for it. Our trio would see them and lean out of their third-floor window to shout: "Looking for Games Workshop, mate? Up here."

"So they'd come upstairs," Livingstone says, "and weren't too disappointed when they went into a rather disgusting-looking living room to mooch around and pull out a copy of D&D, which they happily went away with."

Their landlord wasn't pleased, though. He didn't like all the visitors, and he didn't especially didn't like the way the shared phone downstairs would ring incessantly with calls for them. More often than not, he'd hang up before our trio could thunder down the stairs to answer, and the situation was pushed to breaking point.

The change came when Livingstone and Jackson decided to do Games Workshop full-time, and throw everything at it. John Peake, however, didn't want to. There were no hard feelings: he had a comparatively "grown-up job", as Livingstone calls it, as a civil engineer and so opted to follow that. You have to remember that what they were embarking on then was not common: there was no proven path to follow.

And so, with all the money they had, Livingstone and Jackson went to America to finally meet Gary Gygax and the American gaming industry and buy everything they could. In their excitement, however, they hadn't thought it through.

"We'd given up our flat, we had no office, nowhere to live, ordered loads of games, sent them back to my girlfriend's apartment, and came back to the UK and realised we had a bit of a problem on our hands," Livingstone recalls. Unperturbed, though, and flushed with the confidence of youth, they went to the bank for a loan. But it turns out the bank manager wasn't quite as enthusiastic about Dungeons & Dragons as they were.

"And so you go into the bank manager and say, 'Hey, we got this great game. It's a role-playing game in which you're a hero or a wizard, and you kill monsters and find treasure.' And he looks at you rather like a dog watching television," Livingstone says, "completely freaked out by what we're saying, and asks us to leave."

Reality struck. "And the reality was that we had just about enough money to rent a small office off the back of an estate agent, which we called the Bread Bin - it was tiny - and we were obliged to live in Steve's van for three months."

Still, they made the most of it. They joined a squash club nearby to shave and shower in the mornings, and then they worked at the Bread Bin until midnight, doing mail orders, before heading back to their "stinky old van" to listen to the radio and fall asleep. "We called it living the dream," says Livingstone, smiling.

"And this continued for a few months until we finally could afford a really awful flat on Uxbridge Road in Shepherds Bush and then, ultimately, we were too big for the estate agents to handle any more, so we said, 'Well find us a premises we can operate out of and that's how the first Games Workshop shop appeared in 1978."

It was on Dalling Road in Hammersmith, and it opened 1st April 1978. They'd advertised it in their White Dwarf magazine, which succeeded Owl and Weasel, but they were still nervous no one would turn up. "When we saw the queue waiting there for the shop to open it was [an] amazing feeling," Livingstone says. And the rest, really, is history.

But it's still another year before Fighting Fantasy was born, though the idea had been propagating in their heads ever since playing Dungeons & Dragons years ago. What if they could find a way to make it appealing to a wider audience? What if they could strip down the game system and make it less of a commitment for a casual reader? They really wanted to share that experience with people.

The spark came in 1979, when the Penguin book editor Geraldine Cooke visited one of their Games Days at Games Workshop and saw people playing D&D for herself. "She was fascinated by what was happening at Games Day, [where] literally thousands of people were playing D&D in a very frantic way," Livingstone says. "And she said would we be interested in writing a book about this phenomenon called Dungeons & Dragons?"

That was their chance. "And we said, 'Well rather than writing a book about the phenomenon, why can't we write a book that allows you to experience what it is to role-play?"

"The reality was that we had just about enough money to rent a small office off the back of an estate agent, which we called the Bread Bin - it was tiny - and we were obliged to live in Steve's van for three months"

Intrigued, Cooke agreed, and so Livingstone and Jackson went away to write a synopsis for her to take to her higher-ups at Penguin. And they called it The Magic Quest, and it had a branching narrative and "suggestions" of a game system in it. "And she took it away, Geraldine, to her editor at Penguin Books, and up to the senior editors," Livingstone says, "who apparently laughed so hard their heads hit the table. The idea of an interactive book was preposterous and no one would ever buy them.

"But she, to her great credit, carried on batting for our concept and, ultimately, she managed to convince the Puffin editor [Penguin's children's label] this would be a good thing for children rather than adults. So three years later, Warlock of Firetop Mountain came out."

Now, if you've ever read Fighting Fantasy books, you'll know how complex they can be. Adventures jump back and forth across many pages as you make decisions, hopping from page 44, say, to page 275, over and over again. It's hard enough keeping track of where you're going as a player. But the actual method involved in putting them together isn't as complicated as it might seem. And it's remained largely unchanged since the very beginning.

"For me," Livingstone explains, "it's a case of having four-hundred numbers and then you start keeping a record of the adventure on a flowchart." It was originally 399 numbers in Firetop Mountain, until Steve Jackson said let's round it up to 400 to make it neater.

"So you allocate number one as a starting point and that splits to seventy-seven and three-hundred, for the sake of argument, and you make notes and annotations against each point. So you're keeping a record of this multiple-choice adventure going forward and bringing them back in pinch-points, to one point, so a reader can have essential information which shouldn't be missed. But the technique hasn't changed."

But he writes it into a computer now, whereas he used to use a fountain pen. He still hand-draws the maps though, and he rummages around trying to find the map for his new book Shadow of the Giants while we speak, with no luck.

There weren't many creative disagreements, surprisingly, though they did disagree about which player statistics to put in the game. Ian Livingstone wanted something like strength and endurance, Jackson recalls, whereas he preferred skill, stamina and luck. And they had a novel way of deciding it. "We'd go around [to Ian's house] and have a game of snooker for it," Jackson says. "It was a good way of sorting out disputes, really. But he always used to win."

Firetop Mountain would, however, be the only book they would co-write. I've seen some talk of this being because they could write them faster on their own, but in actual fact, it's because writing them together is harder than doing it alone. "Handing over multiple story points to another author is quite a cruel thing to have to do," Livingstone says. It's what he did in that first book, writing up to the river and Jackson taking over from there. Jackson would actually "very graciously" offer to rewrite Livingstone's part in order for the book to have one voice.

Beyond occasional differences, then, their friendship has remained admirably intact - even across many years living and working together, and sleeping in a van together for a few months. "Nothing's going to ever destroy our friendship," Livingstone declares. "We've been friends now since 1966 so that's quite a landmark period of time. We've obviously had our differences of opinions but they've never become a problem that we couldn't resolve very, very quickly. We always put the friendship ahead of any possible disagreements."

After a slow start, word about Warlock of Firetop Mountain got around schoolyards and sales picked up, and a sluggish Penguin eventually asked the two authors to write more. And from 1982 onwards, their pens barely left the page, writing more than a dozen books in only two years - sometimes turning them around in as little as a month. And the books would go on to become, as Livingstone rightly says, "a national phenomenon", amassing more than 20 million sales and earning them best-selling author titles in the process.

But you have to remember that Fighting Fantasy wasn't all they were doing at the time: they had an expanding business to run as well, and cumulatively, it was taking its toll on them. "We were running Games Workshop during the day, coming home to our respective homes and having to write Fighting Fantasy game-books from eight-PM to two-AM in the morning," Livingstone says. "And that was having quite an impact on our sanity."

They enlisted help in the form of guest authors, publishing them under the 'Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone Presents...' label, and with their help would produce 59 books before Puffin decided to call Fighting Fantasy a day in 1995. They also decided, in 1986, to appoint a man called Brian Ansell as managing director of Games Workshop "to give us some breathing space to carry on writing Fighting Fantasy", and in 1991 he made them a buyout offer which they accepted.

From there, they'd head into video games of course. Livingstone would go to Eidos and be instrumental in establishing the iconic Tomb Raider series, among many other things, and Jackson would co-found Lionhead Studios with their good friend Peter Molyneux, who they still meet every Tuesday for their Games Night Club. Funnily enough, they even have a newsletter for it, and a points system and trophies. "But really it's just a spoof gentleman's club," says Livingstone. "We're just having fun."

And Fighting Fantasy would continue. Wizard Books would pick it up in 2002 and run it for 10 years, commissioning six new books as well as re-publishing old ones. Then Scholastic, the current publisher, would pick it up in 2017, commissioning four new books (including one written by Rhianna Pratchett, who I spoke about it) as well as re-publishing many old ones. And here we are, 40 years later.

But what makes a particularly good Fighting Fantasy book? Well, there's immersion and a good mixture of choice and consequence, they say, and a nice variety of encounters and monsters and puzzles. But arguably the most memorable feature is the deaths. "As you'll probably remember, you die a lot in Fighting Fantasy," Jackson says.

"Steve's Games books were always more difficult than mine," Livingstone jumps in. "I think he delighted in torturing people more than I did."

And it would worry them, the difficulty being what it was. "But the more difficult they were," Jackson adds, "the better the fans used to like them."

Particularly fiendish highlights of theirs include the maze of Zagor in Warlock of Firetop Mountain, because teleported you around and messed up direction-keeping; the shapechanger on the original cover of Forest of Doom, because it looked innocent but was not; and the Blood Beast in Deathtrap Dungeon - "that's quite a famous way to end your days", Livingstone says.

"There's definitely going to be another one if the public still wants it"

Deathtrap Dungeon itself is one of their favourites (a video game was made of this not long ago, with the wonderful Eddie Marsan as narrator). And when I ask Steve Jackson why, he says, "A lot of it's to do with the colour cover, I have to say!" and laughs. But in doing so he touches upon something else that's so important to the series: the artwork. The intricate black and white illustrations inside, and the boldly colourful covers on the outside, have always been iconic parts of what Fighting Fantasy books are, and continue to be, about - and both of them know it.

Their other unanimous favourite is Sorcery!, the four-book series written by Steve Jackson, which has its own magic system and carry-over story. "It's an epic," says Livingstone, plainly. And Sorcery! was adapted into a video game series, too, by the wonderful Inkle, and is available on all platforms now. "Fantastic, wasn't it?" Jackson says of Inkle's work.

That, then, is the brief story of how Fighting Fantasy came to be. And remember, you can hear it from Ian Livingstone and Steve Jackson themselves, in more expansive detail, in the full One-to-One podcast. And although the story began a long time ago, it's not yet finished, as proven by new books Shadow of the Giants and Secrets of Salamonis.

"I haven't really stopped, I've just slowed up a bit," Livingstone says. "I'd always say never again, and as soon as I handed the book in, I'd kind of miss it ... So it's never ending. It's 40 years of thinking about encounters and puzzles and problems and horrendous ways of terminating people's adventures." He laughs. "So it's an ongoing thing. And for me," he says, "it's never going to end. There's definitely going to be another one if the public still wants it.

"Thanks very much and may your stamina never fail."

If you got this far, you may also be interested in the new autobiographical book Livingstone and Jackson have written called Dice Men: Games Workshop 1975 to 1985. It's due out this autumn via Unbound.