Why is Paper Mario: The Thousand Year Door so brilliant? Because it embraces Mario for the blank slate he is

After the jump.

This piece is a retrospective rather than a review and contains spoilers for Paper Mario: The Thousand Year Door.

Simply the thing I am? Oli Welsh, gone and much-missed (he didn't die), once made an excellent point to me about the Mario RPGs. There's this brilliant running joke in some of them that I had not spotted until he mentioned it. The joke's simple: nobody recognises Mario when he first arrives in a new location. They don't recognise him up to the moment when he jumps. Jumping is Mario's thing. Jumping, the games seem to be saying, is Mario. Without jumping, he could be anyone.

What this joke gets at is the notion that there's this...how to phrase this? I don't think it's fair to say that there's a hole at the centre of the character, because lots of people feel very strongly about Mario, particularly if they grew up with his games. He hasn't got a hole through the middle of him! But there is a plasticity to the character that allows you to do a lot of different stuff with him. Look at his visual design, which is brilliant but was also originally conceived because of animation limitations. Look at the ease with which a brother was conjured from him via a simple palette swap. Look at the way he's been dropped into sports games, educational games, RPGs over the years. It's because we know who he is, but there isn't so much of him to stop things from being harmonious wherever he ends up. Trevor Phillips from GTA 5 is a huge star, particularly in our house because my wife loves him. But you couldn't put him into an SSX. (Okay, bad example, that actually sounds freakin great.)

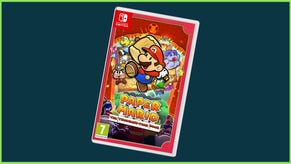

Anyway, no game, if you ask me, has exploited this unusual quality in Mario - this quality of judicious non-quality - as well as Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door. It's a GameCube classic that has just been reissued on Switch, and rather than review another late-era Switch port we thought it would be worth talking about why this game matters instead. (This isn't a review, but if you're after details of the new version, expect updated visuals and lighting that makes the game a lot brighter and cleaner looking. The tutorials are a bit more generous, there's a new quicker way to swap partner characters and an improved hint system. On the downside, it's 30fps rather than 60.)

Is it my favourite Mario RPG? No, that's Superstar Saga, and thanks for asking. But it is the best, the most fully conceived, the most novelistic, and the most surprising from one moment to the next. And that's all because of the things you can do with Mario.

Listen: The Thousand-Year Door is a very good RPG. Mario has great companion characters, all of whom have their own skills. There's a badge system that gives you something to mix and match, the RPGs' time-based battles have never been sharper, and while the main storyline sees Peach kidnapped again, you do get to play as her every now and then, and have interesting philosophical discussions with an alien computer. Luigi gets to go on his own parallel adventure, and he checks back in regularly to tell you how he's doing. It's the first Mario game - at least in the original language - with a trans character. Meanwhile, the papercraft world is as beautiful as it was when the first Paper Mario appeared on the N64. It's all great.

But what makes it stand out for me, though, is the structure. As Mario goes off on his quest to rescue Peach, the game divides itself up into chapters, each of which takes Mario somewhere new and centres on a self-contained story that wraps up in a few hours. There's a castle with a dragon who needs to be defeated, there are pirates, and there's a classic spooky wood with a monster hiding out there. All great. But there's also some really inventive stuff. In one chapter, Mario gets involved in professional wrestling. In another, he finds himself in an Agathie Christie mystery on a posh train filled with suspicious strangers.

.jpg?width=690&quality=75&format=jpg&auto=webp)

.jpg?width=690&quality=75&format=jpg&auto=webp)

These are the parts of the game I remember. The wrestling stuff makes an impact not just for how well it reformats a dungeon and its escalating battles and gives it the shape of a young hopeful's journey rising through the ranks. It's down to how the story engages with everything that's silly and slightly grotty about wrestling - the fakeness, the big personalities, and the money-grabbing promoters.

Meanwhile, the Agatha Christie sequence pokes plenty of fun at the stereotypes of old mystery novels while undermining its own genius detective at every turn, with stupid crimes and obvious culprits. I love the way that The Thousand-Year Door takes the landscapes of an RPG episode here, transforming what would normally be a series of interconnected glades or forests or deserts and turns them into separate carriages all rattling along the tracks together. There's a lot of back and forth, but it's a train, and a train in the grip of mysteries, so of course you go back and forth a lot. By the end of the sequence, I could remember where everyone was staying, and where the luggage was stored and where the driver could be found. It was like living with a mystery novel for a week - one of those perfect weeks when you're consumed by a book.

.jpg?width=690&quality=75&format=jpg&auto=webp)

.jpg?width=690&quality=75&format=jpg&auto=webp)

Mario is ideal for this stuff, and for all the other quick changes the script hands him, and it's because he simply doesn't have too much baggage of his own that might stop you from believing him in any given situation. Tellingly, he's frequently being misnamed in this game. When he's wrestling, he's the Great Gonzalez. When he's on the train, that genius detective deduces that he's Luigi.

It's a game about different roles and artifice, so the papercraft world works perfectly, with Mario folding himself into a paper plane to cross gaps, or turning sideways to slot through grates. And the paper also invokes the flats and backdrops of the theatre - not for nothing do the fights take place on a curtained stage before a live audience. It's all very silly and chummy and am-dram.

And yet if a lot of the game seems to poke fun at the fact that Mario could be anybody, the final battle contains a sequence in which Mario's hopes and HP are restored by the thoughts and wishes of everyone he's met along the way. It's a powerful moment because of the game's innate silliness rather than despite it. In amongst all this tomfoolery there was a bedrock of something real. That's why it all works. It's absolutely lovely stuff.

.jpg?width=690&quality=75&format=jpg&auto=webp)

.jpg?width=690&quality=75&format=jpg&auto=webp)

Someone once told me that the movie Zombieland, which I love, was once a TV series pitch, and the eventual film is just the first three episodes stuck together. If this is true, I think this is why it feels so playful and expansive, why it seems determined to have fun and explore its own interests rather than give everything up for the nine points of a three act structure. Looking back at just the chapters of The Thousand-Year Door makes me think something similar was in play here too. It's a game, and an RPG, and it's a good one - a great one. But it's also a glimpse of some other-world Mario TV series. It's episodic, picaresque, and it gives us many different Marios. And in doing so, it reminds us why Mario works so well as he is.

.jpg?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)