The secret lives of games

From Crytek's spines to Mario's clouds.

If you've always loved Ico for its sparseness - the wind-blasted ruins, the empty space, the near total absence of an overbearing backstory - you probably had mixed emotions about this week's news that fans have datamined the game and discovered that the original script was far longer than the final cut. 115 lines of dialogue for an entire game is hardly chatty, of course, but Ico as we have it now is all about restraint, about the things that go unsaid or unexplained. Will Self has a wonderful word that's worth reappropriating for this kind of thing: under-imagined. It's not a criticism at all in this context (or in his original context), just an acknowledgement that if showing is better than telling, sometimes not showing or telling is better than both.

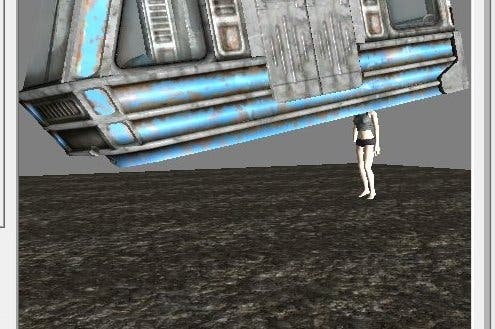

Ico's not the only game that we're learning more about long after the fact. Far more delightful is a recent story about Fallout 3 that suggests that, in order to create the effect of a player riding a subway train, the player was actually wearing the subway train in question. First-person viewpoints can hide an awful lot of fudging: the only thing that truly matters is what ends up on the screen, after all. We expect this trickery with cinema, where years of Behind-the-Scenes TV shows have meant that we now know that the rocks are polystyrene, the skyline is digital, and that, just out of view, the actors can see a bunch of ladders and lighting rigs and assistant directors drinking Frappuccinos. With games, it's a little different perhaps - more along the lines of the mutated spinal monstrosities that Crytek relied on to get crouch animations right for Crysis 2 - but the hidden world is still there, jury-rigged, Scotch-taped, and endearingly human.

The humanity of this stuff is what I find most fascinating: that hidden in the code you get traces of the people who made the game. It's everywhere in code, I gather: comments explaining how a thing operates, or why a thing operates in a very strange way, tacked inside everything from the stuff that controls cashpoint interfaces to the workings of an old NES cartridge. Normally we never get to see this, and that's fine. Because it means on the rare occasions we do get to see it, it makes all the more impact.

I remember a famous post on NeoGAF that revealed the bushes in Super Mario Bros are really just clouds, set at ground level and coloured green. In the context of Nintendo, this discovery has a disproportionately large impact. We sort of expect Nintendo games to be perfect, or at least seamless, allowing no access to the things we are not meant to see. Even when you know that the bushes are clouds, of course, Nintendo has only given a certain amount of itself away. What you're left with is a sense of even greater craftsmanship: a nonchalant and perhaps innate understanding of the way that perception works, and the sort of things that players will never spot, that affords coders and artists a pleasing kind of elegance and economy in their work.

This sort of thing matters, I think, because, despite my strongly held belief that games are amongst the most human forms of art in the world, they don't always seem it. Games often express their humanity in ways that are hard to latch onto: an appreciation, sometimes nefarious, of the way that players approach things, of the sorts of things they will try to do and the sorts of things that will keep them playing. The humanity of a Zelda game, for example, is sort of present in the fairy tale that's endlessly retold with gentle variation, but it's more vividly there in the moment, so carefully orchestrated, that the tumblers of the brain fall into place around a puzzle that has resisted all attempts to solve it, and suddenly an entire dungeon room - an entire dungeon - makes a new kind of sense.

This kind of humanity, vivid as it is, seems somewhat removed, operating at a wordless distance and with great calculation. Sometimes, we don't even get that. Scan the walls of any video game store and you see a lot of soldiers and talking squirrels and shiny cars, created, presumably, to fill a gap that had been spotted by some market technician somewhere.

Turns out it's how these games get made - the compromises and the fudges - that probably provides the most warm-blooded things about them, and that stuff is generally off-limits - or at least it used to be. Stolen glimpses here and there are fine, but the more we get that sense of witty human ingenuity going in the parts of the code we're meant to see, the better off games will be.