The making of Head Over Heels

Rough and tumble with foot and mouth.

There's a distinct feeling of déjà vu as I sit opposite ZX Spectrum coding legend Jon Ritman. The location may be different - we have graduated from his local curry house to a popular pub nearby - but the conversation is still firmly entrenched in the 1980s. "My memory's not what it used to be," admits Ritman, a caveat I've heard many times before while interviewing games industry veterans. "And it wasn't much good back then..."

Fortunately, as I discovered when talking to him two years ago for a feature on his famous football game Match Day, Ritman's short term memory seems to be more the issue. "Only a few months ago I was contacted by somebody about whether I did some loading screens for Crystal Computing," he muses while taking a swig from his pint of lager, which, in keeping with the theme of our conversation, is housed in retro glass mug, complete with handle. "Erm, that was me Jon," I reply, somewhat embarrassed. Ritman is delightfully unconcerned. "Oh, right. Well, yes, I did do some as it turns out..."

Match Day may have been Ritman's breakthrough hit, but it was with his next game, Batman, that his name became firmly associated with high-quality arcade adventures. "I was handing over Match Day to Ocean's David Ward," he explains, "and he said I needed to look at this." Ocean were acting as distributor for Ultimate, a fellow software house that had already become renowned for its exceptional standard of games thanks to a roster that included Jet Pac, Atic Atac and Sabre Wulf.

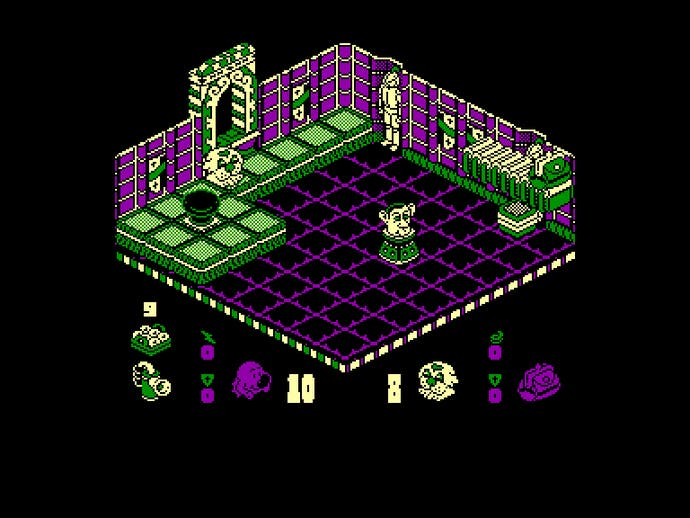

"They gave me a copy of the game, I put it on and was just blown away. It was a Disney film you could play. It was just...great." The game was what many still today consider Ultimate's finest hour: Knight Lore. "I was just going 'how the fuck do they do that?'" smiles Ritman. "I didn't even understand how they made the graphics overlay on each other. Cleanly, and not in straight lines, in diagonals too. So I went home and started to try and work out how it was done, and work out a system that did it better."

Unbeknownst to Ocean, the freelance programmer was beavering away on creating an isometric game to rival Ultimate's own range. Enlisting his friends Bernie Drummond and Guy Stevens to help with graphics and sound respectively ("I could see straight away that there was no way I was capable of doing the standard of graphics the type of game deserved and I'm really crap at music,"), Ritman realised a recognisable character would give the game improved publicity. "I kinda threw up the idea of Batman, which to me was the Batman of the 60s series, although I assumed nobody was going to remember that. But Bernie knew some kids he played football with over the park. He said the series was being reshown on Channel 4, and they were all watching it." Inspired, Drummond designed a Batman sprite and Ritman mocked up a 3D screen for the character to wander around in. Ocean were impressed, and obtained the license with relative ease given it was several years prior to the massive 1989 Warner movie. Batman the game was a big hit and thoughts turned to the next project.

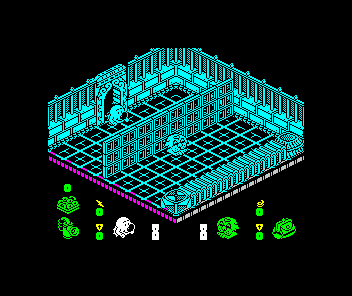

"Head Over Heels was a natural follow-up," said Bernie Drummond when I spoke to him a few weeks ago. "And Jon had perfected the game engine with a few extras which were unique to his programming." Another isometric game, a genre that was still proving popular despite the proliferation of titles, was indeed a logical choice. Explains Ritman, "I'd enjoyed the process and the programming [of Batman] - and it was a challenge, like doing a Sudoku." The two men began brainstorming ideas, creating graphics and designing random locations, before Ritman hit upon the idea of having two characters, separated at the beginning, each with its own set of abilities. "We'd made Batman about collecting things to make a game out of it, and I honestly thought of the two characters as just an extension of that, taking it one stage further. I reasoned you could then have a lot more things to add and collect, and it was only after I'd hit upon the idea, I realised you could split them up and force the player to make them re-join." Each character had differing traits: Head could jump higher and fire doughnuts to stun enemies, while Heels could run faster and carry objects around in a bag. The merged creatures combined these abilities, helping to solve even more puzzles.

Ritman set about designing his game, working on a schedule of 20 rooms per day, with around three-quarters of those rooms containing puzzles. "I was shuffling things around, putting them together, moving them about. I had an editor for the rooms, so I'd try something out, then move it again. Some bits were laid out and drawn on paper, and then I'd just put them into the computer and see how it looked and worked. Sometimes it didn't work and the screen would be too difficult. Then I'd flip the room around to try and make it more understandable. I employed that technique a lot. When I needed fresh graphics, I'd just ask Bernie to send me some stuff that looked cool."

In what seems today a remarkably loose way of games creation, the two men would trust each other's instincts to come up with the goods. "The graphics were created using a well-tried and tested technique," Drummond told me, "In short I'd just draw, letting my imagination fly. Any images that looked good, fit a purpose, or inspired more puzzles and graphics, were kept." The method resulted in a range of bizarre images, not least the main characters themselves, and a weird Dalek/Prince Charles hybrid. "Jon developed a sprite stacking system which we then used to increase the amount of monsters in the game by mixing and matching. The Prince Charles head was originally Plug from the Bash Street Kids, but Jon felt it looked like the Spitting Image puppet of Charles, and that that would be more popular with the public and games journalists."

Ritman smiles when I mention the crossover. "I recognised that you could go down two routes with this type of game - either you had realistic proportions, which meant a lot of things looked crap because they were just too small - or, as Bernie convinced me, you abandon any idea of proportion and make the face half the size of the body. I told him to do that, and just draw things that looked luscious, and not to worry about scale. I remember the journalists wrote stuff like, 'these guys are mad, this looks fantastic!', so it must have worked out ok."

While Ritman is vague on the genesis of the main two characters, Drummond was able to give me a little more insight into how they came about. "Head is actually based on an original cartoon character called The Park Creature, who was an animal trying to get by living on an industrial estate, surrounded by thugs and dumbies. As for Heels, that came from wanting to give it a bulldog-chewing-a-wasp look - a reference to the fact that he had to carry Head around most of the time!".

Like many isometric titles, Head Over Heels is a big game. Really big. "I just made the maps up as I went along," says Jon, to my incredulity - it seems astonishing that such a renowned well-balanced classic had its map designed on the fly.

"I mean, I recognised the need for alternate routes, and I'd try and make one arcade-style and the other more cerebral. The different planets stemmed from that: if you didn't like one planet, you could just go back to the moonbase and choose a different route. I knew it was going to be big, so I had to split it into sections anyway. Having objects to collect was an obvious step from that, and it kinda progressed from there."

As development proceeded, the game attracted the interesting working title of Foot and Mouth. "That was our original name, and we got a bit attached to it. But when we showed Ocean the game, David Ward kept saying, 'We can't call it that!'" The result was a brain-storming session at Ocean HQ, with lyric and song writer Bernie Drummond touting a few ideas including the quaint Rough and Tumble. Eventually, Head Over Heels was declared the winner.

Completion imminent, Ritman proceeded with his rigorous bug testing. A perfectionist, he would frequently track bugs while coding to avoid consequent errors. "But one got through...only one..." he grimaces, draining the last of his pilsner. "A friend of mine came round and wanted to play the game. I popped to the shop and was gone five minutes. When I came back the game was frozen!"

With Ritman's friend unaware of how the error had occurred, he repeated his game, and the error occurred again. "It was basically to do with the order that the characters went into a room. If they went separately into this room then one of them died and the game crashed. It was a fundamental flaw in the game's logic, but it had already been released by then." In all the time Ritman had been testing, the bug never occurred, and nobody else ever reported the error. "I went through the code and saw how it happened. It's in all versions of the game."

After completing the Spectrum and Amstrad versions of Head Over Heels, Ritman guided C64 programmer Colin Porch, helping him create one of the best isometric games on the computer. But did he ever worry that the proliferation of Knight Lore clones would see Head Over Heels, however good, fail to impress the market?

"Not really," Ritman grins, the pub around us now sparsely populated, even for 10pm on a Tuesday night. "I was confident not only was it good, but it was simply more playable, and there were a million little reasons that I always paid a great deal of attention to the playability and how the game felt on the joystick." As with some of the technical exposition Ritman regaled me with two years ago, he's at the salt and pepper pots again, this time not to explain Match Day's player control method, but a key technique in Head Over Heels. He positions the seasonings a short distance apart and slowly moves an upright teaspoon towards them.

"This actually started before Head Over Heels, but it's about lining things up. I didn't want players to have trouble going through a doorway. So when you approach a doorway, the game does the opposite of what happens if you push an object - so essentially the doorway would push the player into the centre, and through into the next room. I played games where you had to go backwards and forwards, lining up, and I felt it much better not to have to fuss over things like that." Primitive by today's standards of video game physics, but it did the job.

Ritman's attention to detail did not go unnoticed in the gaming press of the time. Crash Magazine awarded the game 97%, while sister publication Zzap!64 went 1 percentage point better with an incredible 98%. Atari 8-bit, MSX, and 16-bit conversions followed, and in later years, several PC remakes. Yet despite its success, Head Over Heels never received an official sequel. Colin Porch began working on one back in 1989 but it never materialised, and a recent brief resurrection was curtailed by illness. Says Ritman, "It was clear to me that by 1988 it was the end of the Spectrum era and I kinda bypassed the early Atari ST and Amiga scene because I went to work for Rare." In an interesting footnote to the Head Over Heels story, its creator found employ with the very men that had inspired him: The Stamper brothers.

I finish by asking Ritman which of his most famous 8-bit creations he is most proud of, an admittedly below-the-belt question, akin to asking a parent their favourite child. "I probably enjoyed making both this and Match Day, but for different reasons," he replies neutrally, "Although Head Over Heels was more rounded. Match Day was always a bit slow and the graphics weren't great. But Head Over Heels is still playable, and still looks good today". Indeed it does, I agree, as Ritman and I swap goodbyes for the second, and hopefully not the last time.