The Luddite Game Maker

Jason Rohrer on life, death, video games and diamonds.

Infancy

Many video games features death, but few appropriate it as their theme. For Jason Rohrer, the only video game designer to have been featured in Esquire magazine's list of creative geniuses, it was a slender yet focused game about mortality with which he made his name.

"I was about to turn 30, about to witness the birth of our second child, and had just watched a neighborhood friend wither and die from cancer. As such, I was thinking about the passage of life - and my inevitable death. I wanted to make a game that captured the feelings that I was having: existential entrapment bundled together with a profound appreciation of beauty. These are feelings that are hard to put into words."

And hard to put into a video game. They're harder still to sell to audiences and yet, upon its release Passage spread fast around the world.

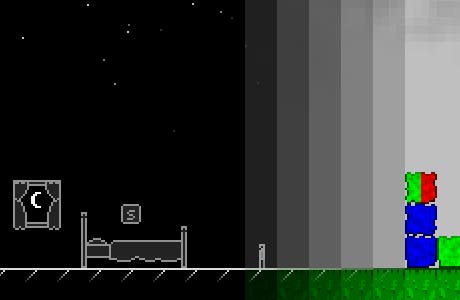

It is an unlikely success story. Here's a game in which death is inevitable for the player, with no hope of respawn. Your character, who can only move from left to right across the screen, ages incrementally with each step. Whereas Jonathan Blow's Braid tethered the passage of time to the passage of space to create mind-bending puzzles, Rohrer's work offers no solution to the profound sense of inevitable demise.

The majority of video games are obsessed with the evolving of an avatar, pressing perks, augmentations and stat bonuses onto the player as rewards for progression. Here was a game that stripped away your speed, robbed you of your beauty, took away your loved ones and decimated your family, and finally yourself in step with progress.

Who would make a game like that?

Boyhood

"I grew up in Bath, Ohio, near Akron," Rohrer says. "It's a place of gentle rolling hills and forests. I spent a lot of time exploring the woods but I also bought video game system after system as I grew up. I have fond memories of the first Zelda and Metroid games on the NES, and also of Alien vs. Predator on the Jaguar. Wolfenstein and Doom on the PC also blew my mind, but we had a Mac at home, so playing those games was a rare pleasure. I also spent time poking around the world of King's Quest, whenever I got myself in front of a PC."

This twin obsession with the escapism in the outdoors and escapism in technology is evident in Rohrer's life today. He and his family practice simple living, earning only what they need to live. He doesn't own a mobile phone, a television or any other gadgets. And yet all of Rohrer's professional life is spent within technology.

"A Luddite building the machines, I suppose," he says, "It's an ironic combination. But the way I live my life gives me more time and attention to work on making games. My life is cheap, so I don't need a job to support myself beyond the income that I make from games."

Adolescence

Rohrer's first game was never released. "In 2002 I spent several years iterating on a game-like project called Subreal. It was an evolution simulator with genetic creatures competing in a shared environment. Each person playing the game ran a sub-section of the world, and these mini-worlds connected together in a grid through the network.

"If a creature moved off the edge of your world, for example, it would leave your computer and migrate onto your friend's computer. I iterated through a bunch of different models for the structure of the world and the makeup of the creatures - 3D flying creatures in caves, cellular creatures, colonies of algae structures, and even a Turing-complete programming language that could be subjected to genetic recombination." "The problem, of course, is that watching life evolve is only interesting for about 5 minutes. What do you actually do in such a game? Even playing as one of the creatures, and trying to eat and mate, wasn't that interesting. Then Spore came out a few years later, which was another reason not to keep pursuing a game about evolution. I think everyone had an evolution design on the back burner before Spore came out. It's a pretty common idea."