The future of Rare

After Kinect Sports, will the legendary UK developer finally give fans what they really want?

"I still feel a bit sad with you guys for the article you wrote about Rare being dead," Craig Duncan, the boss of the Microsoft-owned Kinect Sports developer, says at the beginning of our interview, not in an abrasive, confrontational way, but in a genuine, heartfelt way. I listen and believe it did make him sad. No doubt it saddened a few here.

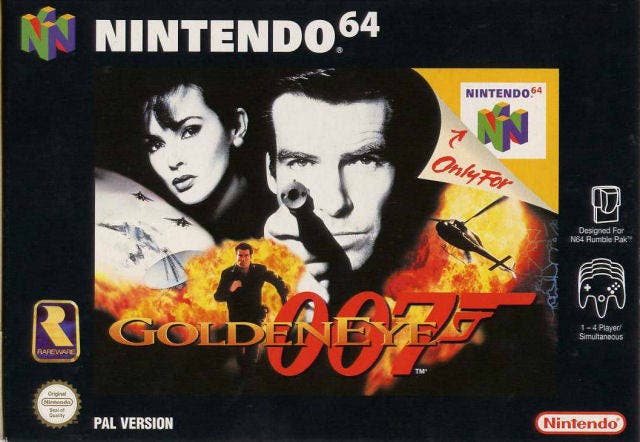

"Who Killed Rare?", written by regular Eurogamer contributor Simon Parkin and published a few months after the release of Kinect Sports: Season Two, asked ex-Rare staff the question most who grew up playing the likes of GoldenEye, Donkey Kong Country and Killer Instinct had wondered for some time. It was a question that came with an assumption: if we're asking who killed Rare, then we're saying Rare is dead.

The article was published just eight months after Duncan, former development director at racing game specialist Sumo Digital, took over the famed studio. "I took it as, I'll show them, because that's what I do."

Two years later, just over three years into the job, has Duncan showed us?

"Rare's evolving and it continues to evolve," Duncan says. We're chatting in a nondescript room situated on the first floor of Rare's main building. I'd spent the day playing Kinect Sports Rivals, due out next month for the Xbox One. Duncan spent the day milling about, answering questions, watching the press gang wave their arms, slam their feet, throw imaginary bowling balls and swing make-believe tennis rackets. Now, though, he's answering questions about the past, the present and - crucially - the future.

"Rare has evolved for 30 years, and it's always been nimble in what it's done," he continues. "It's always done different things. My vision for Rare is it will continue to do different things. We have a bright future. We have a ton of incredibly talented people here.

"For me it's about, how do I make sure I set Rare up to be as successful as it can be and the team here have the creative space and the backing and the budgets to do what they do best, which is make great games?"

Let's talk about comments.

I hear a lot of video game developers say they refuse to read comments on the internet. Not Duncan. "I do read the comments," he says. "I just don't react to all of them."

Whenever we write about Rare, whether it's a news story about a Kinect Sports related announcement or an investigation into how the culture of the studio changed after Microsoft bought it in 2002 for $375m, most of the comments lament the "death" of the studio - and it's clear why: Rare seems to be the exclusive developer of the Kinect Sports franchise, a franchise built to showcase the Kinect motion sensor, a peripheral most core gamers are at best cynical of, at worst would rather didn't exist.

Duncan read our article and thought he'd show us, but the next game from the studio is yet another Kinect Sports title, its third to release in under four years. I'm honest with Duncan: Kinect Sports isn't what core gamers want from Rare.

"We've always got ideas bubbling," Duncan counters, "and there are always things ultimately we could go and make into the next project, and some of that, we look backwards at the IP we own - and we've got a rich portfolio - and some of it is, people come up with good ideas."

Rare is still holed up in the same custom-built rural headquarters in the small Leicestershire village of Twycross where Conker was created and Banjo was birthed. It really is in the middle of nowhere, and unless you know where you're going, you'll struggle to find the door bell. No sign hangs off of the unassuming front gate where GoldenEye-style CCTV cameras keep a watchful eye on all who approach. No public transport worms its way along the country roads from Leicester or Birmingham to Rare's reception. To work at Rare, you must drive.

Rare is still a main building linked to the famous four "barns" - named A, B, C and D - where projects are incubated and games are made. Rare is still surrounded by brilliant, beautiful countryside that stretches out as far as the eye can see. There's a peaceful pond. There are bees and benches outside of the canteen. It is a lovely, relaxing environment in which staff can escape the stress of rigorous triple-A development.

Work on Kinect Sports Rivals is finished. Assuming it's successful, another will probably be made, such is the nature of the hit-driven console game industry, but that doesn't mean Rare isn't working on other, non-Kinect Sports games, Duncan says. Inside the barns we're not allowed into new games are being worked on in secret, he says. Just don't ask what they are.

"You've got to look at the right game idea and the right franchise for the right goal the company has at that time," Duncan says, explaining why 150 people have spent the last two years creating Kinect Sports Rivals.

"For us to light up Kinect on Xbox One, putting something out in the Kinect Sports franchise, and then going, this is what the franchise did before, what can we do in new and interesting ways, was the right way for us to show what the new Kinect sensor could do.

"That doesn't mean the next game has the same goal to show what the new Kinect sensor can do, because I think we've done a pretty damn good job of that this time."

Duncan is right. Rare has done a good job this time. Kinect Sports Rivals just works, which is something many Kinect games have struggled to achieve. While the football (or soccer, puke) game lets the side down by not being much like football at all, and shooting is a bit boring because all you're doing is pointing at targets and the game automatically shoots, climbing is breathless fun, wake racing is a graphics stunner, tennis is surprisingly responsive - despite you having to move your swinging arm slightly ahead of when it looks like you should - and bowling is a blast.

The problem with Rare isn't the quality of its games, I tell Duncan. They are, generally, well made and lovely-looking. The problem with Rare is it isn't making the kind of games its core fans want to play - and that saddens them.

"I grew up playing Rare games, much the same as you, much the same as the people posting comments," Duncan replies. "We all have fond memories of the games we grew up playing and the games we love.

"We would never ever make a remake of a game we made 10 years ago and just put prettier graphics on it and add tick box whatever new features we have on our platform, because that's just not the first party thing to do, and it's not the Rare thing to do."

Rare boss Craig Duncan

"But when we decide what game the studio is going to make, we've got to have more than just that reason. And even if - and I'll take Banjo, I'll take a beloved IP such as Banjo - even if we were going to make a new Banjo game, we'd make that because we thought we could do something interesting with that genre on a new platform with something different that's never been done before.

"We would never ever make a remake of a game we made 10 years ago and just put prettier graphics on it and add tick box whatever new features we have on our platform, because that's just not the first party thing to do, and it's not the Rare thing to do.

"I'd even put Kinect Sports in this category: if you think of everything Rare's always done since the dawn of time it's always picked something that is different and it's done it in a different way. GoldenEye did something different in shooters than any other shooter had done. Even Kinect Sports Rivals does something different with Kinect and motion gaming than any motion game has ever done before.

"Everything has got to have that, 'why is this different?' Why is it innovative based on what other games and franchises have done before? If we just took an old IP and retrofitted a new game to it, I tell you what your comments would be, they'd be, they just took the old IP and just did a generic game with it. People might be happy that old IP lives again, but ultimately they wouldn't be happy with what that was.

"We wouldn't just go, we've got a great idea for kart racing, so let's just make a kart racing game and put Banjo in it, because Banjo is an IP we own. If we can't change what a genre is doing or do something that's really going to make people sit up and take notice, and push that quality... that's how we justify doing something - whether that's new or old."

So, why not just go and do that, then? I refuse to accept Rare struggles for game ideas that would make people sit up and take notice. Why not make a new game out of one of them - or turn to one of the beloved IPs Rare owns to set it within?

"There are many things we've got bubbling from an incubation point of view, and we'll pick the right thing to do," Duncan says.

"The interesting thing from a creative point of view is, we've always got a number of ideas, and we've always got way more things we want to do than we've got people, time, resources and budget to do.

"I'm super excited about Kinect Sports Rivals and I'm really excited about that launching, but I'm also excited about what's next for Rare, because that'll be an important project in the same way."

I press: will people look at this new project and - you know what I'm going to say - will the people who commented on that article say...

"Are they gonna go: Rare is back?" Duncan interjects. "And what my answer would be is, Rare has never gone away. We've just changed and made different types of games.

"Our goal as a studio is to always make great quality games. What you're saying is, will Rare always make Kinect games? What I'm saying is, we will come up with great game ideas and we'll look at the platform that makes the most sense for those game ideas to be on."

"What you're saying is, will Rare always make Kinect games? What I'm saying is, we will come up with great game ideas and we'll look at the platform that makes the most sense for those game ideas to be on."

Craig Duncan

Danny Isaac is Rare's affable executive producer of Kinect Sports Rivals. He joined in November 2011 after a stint at the Brighton-based Relentless Software as studio manager, but before that, he worked for EA on the FIFA series. When he joined Rare he was already used to working at a huge corporation (at the time EA had nearly 20,000 employees), but nothing could prepare him for working within the behemoth that is Microsoft, home to over 100,000 full-time employees. That's more people than you can fit into Wembley Stadium all working for one organisation, Isaac notes. It's massive - and not always helpful.

"Sometimes we get these surveys through from Microsoft corporate saying, hey, fill this out! And it comes up and you think, this has nothing to do what I do day to day," he tells me.

"And sometimes they throw out the baby with the bathwater."

In "Who Killed Rare?", former staff suggest Microsoft imposed a corporate culture onto the studio and pushed it toward making games some didn't want to make.

But despite Microsoft's flaws, it's a friend with benefits. "We've got this 800 pound gorilla that's got our back," Isaac says, "which allows us to do these great things.

"Plus, we're in Twycross, a few thousand miles away and kind of isolated, where we can still keep our creativity and identity, which is important for us.

"To be honest, I'm glad we're working with them. We have exclusive access to the hardware. We know what all the plans are and we can do some really great things. There are very few places where you can change the world, and Microsoft is one of them. If you come up with something innovative enough, you have the backing of making it happen.

"When there are 100,000 people, it could be 20 people in a room all with different opinions. That can be challenging sometimes. You take the rough with the smooth. It's down to us to have conviction in our ideas. And we know games. That's why Microsoft bought us in the first place. We're gamers. We've been making games for years. We're the experts at doing these things."

"If you look back to GoldenEye and Donkey Kong Country, they were real landmark pieces of technology. People remember them because they were great games, but they were also great pieces of technology at the time."

Kinect Sports Rivals executive producer Danny Isaac

Talking to the Kinect Sports team I can tell they take an enormous amount of pride in the technology that powers the series. Rivals is built on a brand new game engine worked on by over 100 people. Visually, it looks lovely - particularly the wake racing - and the champion creation feature, which scans your face and body to create your stylised avatar, is perhaps the most impressive thing a video game has done with Kinect. Rare's passionate new technology development lead Nick Burton has played a crucial role in the development of the sensor, and when he's not in Twycross he is often delivering talks on how it's improved.

"Our passion is new technology, and the new sensor is part of that," Isaac says. "If you look back to GoldenEye and Donkey Kong Country, they were real landmark pieces of technology. People remember them because they were great games, but they were also great pieces of technology at the time."

Despite this passion for working with new technology, I just can't shake the feeling that Microsoft is the villain in the story of Rare's output post-2008's Banjo-Kazooie: Nuts & Bolts, so I dig into the studio's relationship with its corporate paymaster.

Microsoft's European development studios are run by Phil Harrison. Craig Duncan and his opposite numbers at Lionhead, Soho, Lift London and Press Play report to the ex-Sony executive. Then there's Phil Spencer, who runs the Microsoft Studios group from Redmond. "I speak to those guys regularly," Duncan says. "They absolutely have the same goals as we do: to make great, creative projects that showcase our platforms.

"Of course, everyone wants to create a hit. There's no magic formula for creating a hit, so we do new innovative, cool stuff, and hopefully, as I hope with Kinect Sports Rivals, we'll release it and people will like it. And if people like it, they'll buy it and that creates success, which ultimately helps greenlight other projects."

Duncan says the two Phils "don't necessarily want to know everything that's going on at Rare," but, as you'd expect, new projects are discussed before they're given the thumbs up. "We present some ideas, and there will be feedback, and a back and forth. We've got to look at what's in the Microsoft portfolio, where is the industry going and what capability we've got in the studio, and make sure the stars align. Because if you don't align those stars, we'll either make something the industry won't want or we'll make something someone else in Microsoft is making.

"So we've got to look at portfolio, industry and capability as a studio, and try and thread the needle with the best idea we think has the best chance of success."

"Actually in Kinect Sports Rivals there are a few nods to our past. If you look closely you'll find them."

Danny Isaac

Success is an interesting word. The first Kinect Sports game was a huge hit - one of Rare's biggest ever. Sure, it benefited from being a launch title for the heavily-marketed Kinect for Xbox 360, but it still did the numbers. Now, there's an expectation Kinect Sports Rivals will repeat the trick. All in all, the Kinect Sports franchise has shifted 8m copies - a number not to be sniffed at.

So, perhaps we shouldn't be surprised that Rare has focused on the Kinect Sports franchise over the last four years. Microsoft is a business, after all, and for Rare to survive it has to pull its weight. Perhaps - whisper it - without Kinect Sports, Rare might not be around today. "I don't think we're saying, yeah, we're Kinect Sports forever and ever," Isaac says, "but we've had a lot of success with the title. If people are entertained by our products then we're doing the right thing."

In Rare's canteen a shelf proudly displays the studio's best work. Shrink-wrapped copies of GoldenEye and Perfect Dark sit next to a 64DD, that curious, bulky peripheral that plugs into the underside of the Nintendo 64 console. It is a heart-warming collection that rekindles memories of long summers spent playing the best games around.

I hope Craig Duncan shows us and adds to it.