The Banished Vault review - dense and brilliant, like a neutron star

Hard sci-fi.

Like the beginnings of the universe, The Banished Vault starts out impossibly dense, before expanding outwards into something brilliant. On first glance it's almost inscrutable - but it's also tantalisingly simple. You, a crew of maybe half a dozen intergalactic monks, stranded at the frontiers of galactic exploration, have encountered something called The Gloom, a virus of darkness consuming one solar system at a time. Guided by little more than a glorified abacus and your wavering faith, you must outrun it for long enough to chronicle the mysteries you find here at the edge of existence, holding out against the rushing darkness to transmit your findings back home. You arrive somewhere. You research something. You move on in time to survive - manage that four times and you're done. When it all clicks, and the fog of numbers and tables and energy calculators clears, it's magic.

But first: the density. The Banished Vault is consciously designed as a kind of virtual board game. The universe is rendered flat here, your ships moving like pieces on a board, the board itself a generated map of a solar system, with several planets and their moons around a central star. At the start of each run, and each trip to a new system within it, The Auriga Vault, a vast galactic monastery and your suitably gothic, 40K-inspired home among the stars, arrives and waits at the edge of this solar system, while your three starting ships and six starting monks - called Exiles here - arrive with it.

To get to the next solar system safely, you'll need to gather enough resources and construct the right buildings on the available planetary surfaces to create something called Stasis, which your Exiles need to survive the deep hibernation between jumps to new systems. That's mere survival, though. To achieve your real goal you'll need to reach a hallowed planet, typically the one closest to a system's sun (and therefore furthest from the safety of the Vault), land there, and construct a Scriptorum, for chronicling the strange, mythic encounters of your Exiles before you move on. The density comes in all the many, many things you'll need to do to actually achieve this. The Banished Vault requires intense micromanagement and nose for efficiency for success - in fact it requires this for it to be fun.

To gather resources, for instance, you'll need to travel to the planets - and, in the right circumstances, their outer orbits - which requires fuel. Fuel requires a Fuel Producer - of course! - which is a building you construct on planet surfaces. Constructing it requires Iron, which requires an Iron Extractor, while crafting it requires Water, which requires a Water Extractor. Each of these requires an Exile to be manually assigned to the building and that building manually operated by you, literally clicking the button to extract or produce the resource in question, physically dragging and dropping it from the building's inventory to your ship's inventory, or in the other direction as required, and all of this before you've even gathered enough fuel for a single ship to move.

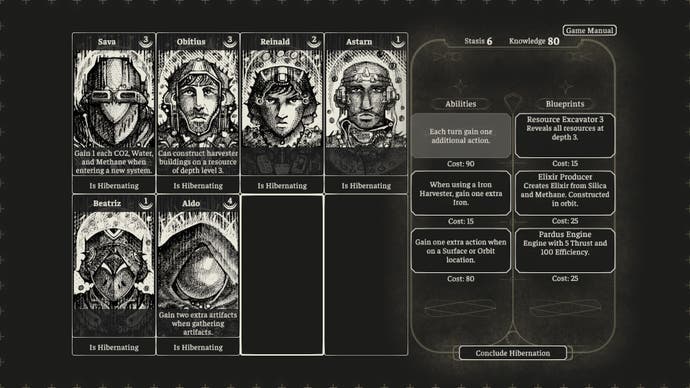

It sounds torturous, and in many ways it is. Part of The Banished Vault's genius is its ability to pit you against that old enemy of yourself. With a limit of 30 turns before The Gloom arrives to gobble you up into the abyss, and a limit of generally one to five things each Exile can do per turn - governed by their action points - but no actual time limit of any kind, your only true obstacle is your ability to focus, to work backwards from an end goal. This is a game played in a race against short-term memory, a battle with concentration, a war against the stubborn refusal - in my stupid case - to write any notes. I write notes for a living! No more! Ultimately if you choose that option you will lose: at later stages you'll need every drop of fuel and every turn of the 30, and you'll mutter to yourself in immersion verging on roleplay, like your little Beatriz and Reinald and the other Exiles fighting off their own temptation to drift into despair.

I definitely lost that final one. "Air Pentad -> Scriptorum; Arch Twenty Three -> Stasis; Sedii 17 -> Fuel" goes one scribble. Beneath that is some basic arithmetic I learned when I was seven and haven't used since, and reminders, now of long-forgotten context, of what I was doing or about to do before closing the game down for a break. Again, a whiff of torture - how is this fun?! The answer, like it is for any game that's brutally difficult, or horrifying, or complex, is the satisfaction of overcoming it. It's attention to detail and care, a game rising up to meet you where you meet it. Give The Banished Vault your real, undivided attention and what it gives back is an almost unparalleled sense of reward.

Much of this is summoned through a sumptuously tactile interface. An energy calculator - a gorgeously simple thing, required in some edge cases for figuring out exactly how much fuel to load your ship with for a longer journey, to that hallowed planet say, and not forgetting the way back - is loaded with a wonderfully haptic tock-tock-tock, the sound of turning dials over warn notches in aged wood or antique brass, the sound of knowledge pre-Enlightenment. And it's conjured through its score, which somehow blends a monkish choir with the pumps and throbs of something like FTL's electronic soundtrack and the raking, echoing metal sounds of Hans Zimmer on Dune.

There's a purpose here, a reminder: you are at the edge of everything, the furthest away you can be, lost at the bottom of the deepest of holes, and you're being hunted - and you have a final, pious duty, to God or science, or the mixture of both, to fulfil before you're through. Come out the other side of that horrible, oppressive vastness - even to just the next solar system, one step closer - and there's little satisfaction like it, the game building into a cycle of tension and release, turning with its frilly-edged suns, from a tricky system to a mercifully gentle asteroid field, and back. It's mixing FTL again, with its system-hopping run from the Federation, with the kind of claustrophobic vertigo you get in No Man's Sky or Outer Wilds, when you venture a little too far from firm land at home.

The same goes for the actual traversal itself, once you have the fuel and whatever else you might want or need to take with you. The distance a ship can move on a given amount of fuel depends on the mass of the ship, the efficiency of the engine you've equipped, and the energy required to move through certain areas of the system (as in, along certain paths on the board). Different ships have different masses, of course, while different engines can swapped out for more efficient ones or, for when landing on planets with different strengths of gravity, different amounts of thrust, yet another factor to bear in mind. Longer journeys also use fuel less efficiently than shorter ones (for maths reasons - don't ask), and so you might want to break them up, expending extra action points of your Exiles in exchange for using less fuel.

All of this, even still, is really only the surface-level of it. Ships have limited storage on board: resources can be stacked up to nine times in a single slot, with your basic ships having just four. Packing a spare engine for higher-thrust manoeuvres might take up one, fuel, like any resource, takes them up too, and so shipping the required resources to somewhere to build the right building, to extract more resources for something else, for something else, becomes the real moment-to-moment of it. In many ways The Banished Vault is like that riddle about getting a fox, a chicken, and a sack of corn across a river in a single rowboat.

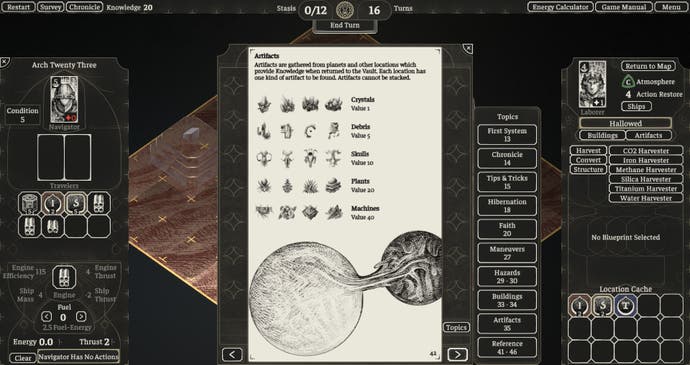

The finest of arts is suddenly the ability to figure out exactly how much fuel you'll need for a two-way trip, packing enough to get there but also only enough, so you'll use exactly the right amount to free up an extra slot on the way out, for carrying more items back with you on the way back. Then there's a Knowledge resource, earned by digging up Artefacts from planets and returning them to the Vault, which can then be spent on either unlocking new ships, buildings, and engines, or select upgrades for your Exiles, like the ability to gather three Artefacts at once say, when travelling to new systems.

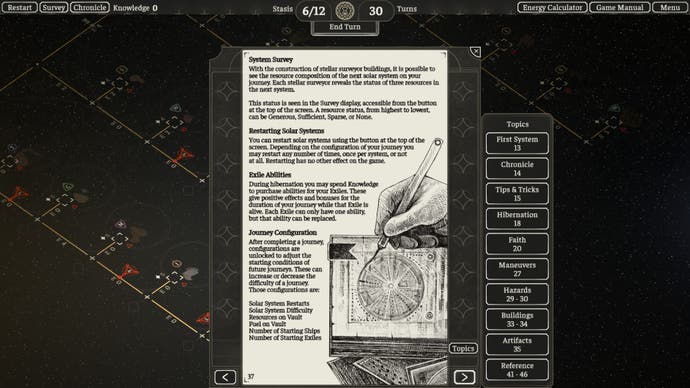

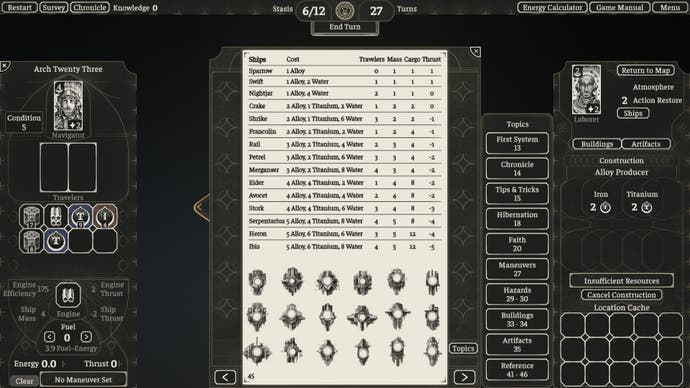

And, heaven forbid I don't mention it, there's the manual. My hope is that reading all this explanation has felt at least a tiny bit less interminable than having someone read the instructions to you from a new board game's manual, but that might be pushing my luck. The reality is you will need to read it - it's provided in-game but you can buy a nice little physical one, if you wish - and this, I can't stress enough, is non-negotiable. Fortunately it is beautiful, sketched with scratchy, pointy, gothic pencil lines that contrast sharply with the soft woodblock curves of its little pieces on the board.

You'll need to reference the manual for how The Banished Vault's systems work, checking and checking again before moving anywhere or doing anything, referring back to the dedicated "Reference" section at the end of it right until the end of your final run, to double-check how much Alloy you need to build a Stasis Producer, whether it was that or the Elixir Producer that needed two Titanium to build. (Elixir! Another system! You need Elixir to top up your Exiles' Faith between systems, their Faith being their version of health, and the governing stat behind how many dice you roll against Hazards that you'll regularly encounter along the way). There are one or two things it could've explained better: I'm not sure I ever read anything about rotating buildings being possible, for instance, instead discovering that in my third system after happening to see a GIF on the game's store page.

And still, the pleasure of getting this right - after a guaranteed period of confusion and frustration and toil - is wonderful. It's also not even the real wonder of The Banished Vault. That comes instead from just stopping to take it all in, to look at it and think about how beautiful all this is.

So often games present themselves as destinations for tourism: look at that sunset we made, that mountain, that grandly choreographed, minutely engineered view. I've always found those moments failed to hit me in any way like the real thing because of their very nature as artificial. The magic of a view - a real view, if you've ever been fortunate enough to look out over a mountain range from in amongst it, or just out your window at the clouds one day, or along the beach at dusk, up to the sky on a clear night - is that it's real.

The power of a beautiful view comes from the almost-but-not-quite-impossible good fortune of it existing, of all the infinite variables that came together to leave you existing in that place, at that time, to be able to witness it, and because it's there entirely independently of anything you or any other human has done. This is the real genius of The Banished Vault, because really on top of its simplified (but still, again, desperately intimidating at first) take on chemistry and engineering and suffocating, operatic grimdarkness, this is a game about mathematics. That other impossible, divinely beautiful thing that can't be engineered into something pleasing to the eye, but simply exists, through a god or through science, as naturally-occurring magic. I can't remember another game that captured it.