Sunless Skies review - a rather more accessible literary space monstrosity

Victoria's secrets.

After 45 hours in Sunless Skies, it's tempting to offer your own spin on Roy Batty's "I've seen things you wouldn't believe" speech from Blade Runner. The problem is that it's hard to know where to start, and even harder to know where to stop. A hybrid, like 2015's Sunless Sea, of top-down steampunk naval sim and choose-your-own-adventure storytelling, Skies takes you everywhere from an asteroid circus to the howling corona of a clockwork star. Blending the juicier nightmares of Victorian astronomers, bureaucrats and sailors with some rather less antiquated-feeling characters and concepts, it's a tour of the heavens in which every port is an oddity, twinkling or at least glistening in the firmament.

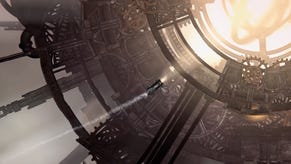

Pick random moments from my playthrough and you'll find my captain doing something very different each time, all of it brought to life with Failbetter's trademark mix of dread and whimsy. Here I am having sex with a demon signaller, for example. And then there was that time I visited a laughing orchard to resolve an academic dispute about the exact occupant of a celestial tomb. Here I am trading shots with a ghost of wood and parchment as I skim the lip of a black hole - oh, and of course, here I am devouring my own crew after running out of fuel on the way back from hell. The great joy of Failbetter's latest is once again the ghoulish inventiveness of the writing and setting, though it's helped along in Skies by more accessible world design, relatively generous earning mechanics and some truly decadent background art.

A direct narrative sequel to Sunless Sea, the game's premise is that Queen Victoria has conquered the solar system, ensuring that Britain is, indeed, the empire on which the sun never sets by murdering the sun and replacing it with a mechanical one. She's also achieved immortality by somehow mining the raw stuff of temporality itself and selling it by the barrel - a wonderfully silly and brutal co-opting of the theory of relativity. In this universe, royal stipends are measured in hours, not coins, and time passes a lot slower inside factories than in palaces, the better to exact maximum blood and sweat from each labourer. Out in the solar system's recesses, meanwhile, upstart "Tackety" colonists battle London's representative the Windward Company while demons, the dead and other, even stranger entities go about their business.

The sight of the old star's bloody ember rolling beneath you is one of many grotesqueries you'll process as you trundle, once again, around a 2D plane in your trusty steamship, buying coal and food at ports while pursuing hundreds of branching stories and doing your best to keep your crew both alive and sane. Your captain has the same four core skills as in Sunless Sea - they correspond to perceptiveness, stealth, strength and charisma, though one of the game's beauties is that what each skill actually does is a little ambiguous - and most quests test one or more of those skills with a roll of the die. You might have to gamble with your Hearts skill to woo the servants at an aristocratic masque, for instance, or test your Mirrors to find the contraband in a bandit's hold.

The return of a successful formula aside, the broad similarities with Sunless Sea reflect how outer space has long been a literary cousin of the ocean, as scientists, engineers and sci-fi writers seek to express its immensities via the more familiar language of nautical miles, (solar) winds and constellations. In this case, outer space is also breathable, suffused with vegetation and thoroughly British, made up of references to particularly eccentric or blighted aspects of British culture, geography and history. The environment art rises to the challenge with aplomb. As with Sea, much of the thrill comes from the sight of your tiny vessel hurrying across a delicately layered vastness of painted backdrops, but the backdrops are far more detailed and animate, to the point that they almost upstage the writing. Almost.

In the Reach, the game's starting region, you'll find golden Spenserian forests where pirate vessels dart about like pike, and warrens of fungus that seem to clench around your ship. In the aether over London, Dickensian "workworlds" open furnace maws in the sooty distance, while half-glassed wrecks bake in the hellish radiance of the Clockwork Sun. There are ports modelled on cosy Somerset villages, complete with cricket lawns and bunting, and a leafy hothouse patch that suggests the artists have spent many an idle hour in London's Kew Gardens. Each port and region has its collection of orchestral themes - mournful, upbeat, oppressive, reassuring - but the game's audio is often more powerful in the silent stretches, when the chug of your engine is your only comfort against encroaching shadows. The least welcoming of the game's regions is Eleutheria, a breathless midnight realm which combines Christian devilry with pagan ritual and a knowing touch of the Orient in the form of Victoria's great rival, the Khanate, basking in the glare of an electric moon.

Much of this you can glean from screenshots alone. What's less apparent is the change in underlying structure. Divided into four regions whose contents are shuffled around a bit each time you start over (there's the option, once again, of reloading your last save on death or beginning afresh with a new captain) Sunless Skies is much bigger than Sunless Sea, but it's also more digestible. Each region has a central port, which is the only place where you can buy new ships and - save for the odd bit of plating pilfered from a defeated captain - patch the holes in your hull. It's also where you'll sell off most of the stranger commodities from outlying ports, and take on Prospects: simple trading missions that give you more cash per keg of human souls or bolt of spectral fabric, with a commission on top to boot.

The Prospects obviously make it easier to enrich yourself, but more importantly, they also come with rough compass headings and thus, guide your hand as you peel back the fog of war. It's part of a broad clarification of the Sunless style. Skies is still a game that will happily destroy you if you're reckless - moreover, it's a game that is often more fun when you do screw up, and must deal with the effects of starvation or crew hysteria. But it's not as painful to master as Sea, and a trifle harder to get lost in. Commodities and the places where you can sell or make use of them are more conspicuously grouped, easier to memorise. There's also more opportunity to resupply en-route, each region being strewn with randomly generated lootable artefacts, from sad little clouds of locomotive wreckage to ancient libraries ripped from their moorings.

The difficulty curve is steepest when entering a region for the first time, with safe havens easily missed as your scouts (including one-eyed owls and a guinea pig riding a bat) point you towards things you'd really rather steer clear of. But it levels out soon enough, as you fill in your skychart and identify the best routes - a course that takes you past a monument to The Unknown Rat, raising crew morale, or a slight detour in hopes of depriving some marauders of their latest catch. Managing your ship's hold is still the key challenge on longer trawls - fail to prepare for the worst (or best), and you might have to cast priceless finds like panes of stained glass out the hatch to create space for ship's biscuits. But there's now storage available from the get-go at each central port, with stored items retrievable at any other region hub.

The combat is cleaner this time round, too, closer in tempo to an arcade shooter. You no longer have to click enemies to target them, or wait for a firing solution. You can also now strafe, sliding around cannonfire on a jet of steam, providing you don't overheat your locomotive by firing too often. I wouldn't buy the game for its steamship duels, nonetheless, but where in Sunless Sea combat was at best a source of tension and at worst annoying, here it's actually enjoyable. The enemy AI is fond of bouncing off the scenery but will often test your mettle, and there's the odd exciting three-way when ravening skybeasts chase you into the arms of an enemy faction.

Above all, though, you'll still be playing Sunless Skies for its writing, which oscillates between fairytale, gothic horror and comedy of manners. The script is never short of a grisly implication or contemporary parallel: as with Terry Pratchett's novels, it excels at holding up a carnival mirror to various social or historical quagmires without giving you a lecture. But it's never short on absurdity, either. It revels in both the cruel grandiosity of empire and the little intimacies and stupidities that keep such an enormous machine in motion. Consider its obsession with tea - stewed, nectar-infused, fungal, hallucinogenic, diabolical, with milk or without, even vaguely sentient. Characters range from circus clowns to princesses, and there are many different gender identities and sexual orientations, but one thing everybody seems to share is the love of a good brew. The script is leggier than in previous games, closer to a collection of short stories than a mass of fragments, as Failbetter gravitates away from the sparer prose of 2009's Fallen London. In particular, the officers you can recruit to boost your stats - each embarked on a little odyssey of their own - are much more involved as characters. It's always a pleasure to sift through, as rich and sickly as a rotten tapestry, though I did occasionally miss the terseness of the developer's other titles.

If that wit and imagination is why we play Sunless Skies, the game's gentler design is what makes it a worthwhile advance on Sunless Sea. It is at once a more florid artwork and a more considerately built one, with a few more toeholds for the wayward captain. There's still much to deter a newcomer, all the same. If you found Sea frustratingly oblique and demanding, and you struggle with the idea that every great story includes a few cataclysmic setbacks, the new game's nips and tucks may strike you as too little, too late. But if you adored Failbetter's previous work, you're drawn to tales of gruesome misadventure or you have a taste for outlandish portraits of imperial hubris, well - your cuppa runneth over.