Why Do Developers Give Away Their Games For Free?

Something for nothing.

It's often said that gaming is an expensive hobby. Major new releases retail for as much as £50, and with dozens of supposedly 'must-play' titles launching every year, the pennies can be quick to add up.

But brewing away beneath the surface of the industry - beneath the main bulk of the indie scene, even - is a world where money appears meaningless. It's a world in which developers pour their talents and their time into the creation of fantastic computer games, for which they ask nothing in return.

It's true that many of these free games are throwaway Flash efforts. But there are some gems: free releases that offer hours of play time, intricate stories, and fascinating game mechanics. Many developers working within this scene could easily justify demanding a few pounds in return for a copy of their latest masterpiece - so what compels them to say 'put your wallet away'?

For Christine Love, the debutant developer behind Digital: A Love Story, charging for her work never even entered her mind.

"It's not because of any lofty intentions," she admits. "I just never even considered the possibility that more than a dozen or so people would actually be interested in it. That was what my readership consisted of at the time, so the idea of trying to make money out of Digital never would have even occurred."

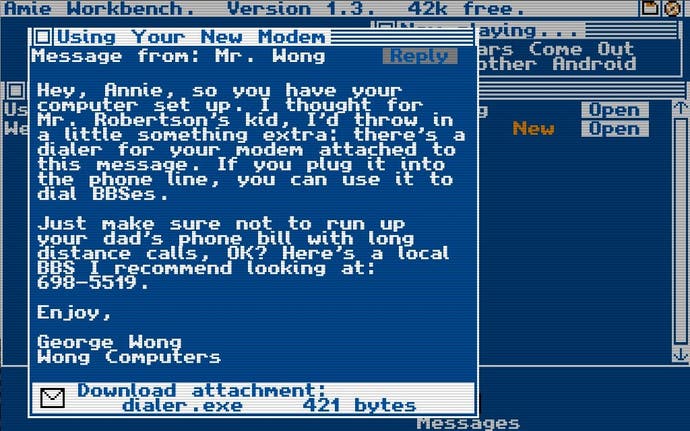

Before making Digital, a science-fiction adventure game about teenage romance at the dawn of the internet, Love was an aspiring novelist. Becoming a game developer happened almost by accident: she wanted to experiment with what interactivity would bring to her words. To her astonishment, whispers of Digital's character-driven storytelling and nostalgic atmosphere quickly spread around the social mediaverse, and her game became an indie hit.

Love isn't the only one to have found surprise success with a free game. Derek Yu was already an established game developer when he released Spelunky, having previously worked on indie float 'em-up Aquaria, but it was his devilishly difficult procedurally generated platformer that propelled his name into the consciousness of many gamers.

"I needed a break after Alec Holowka and I released Aquaria, so I popped open Game Maker and started making little prototypes," he says. Yu was familiar with platformers, and wanted to try combining the genre with a simple roguelike, creating a game where death is final, and no two levels are the same. That game became Spelunky - a title that, several years later, is now heading for commercial release via XBLA.

But it was the free version, first released on PC in 2008, that first saw people raving about its quality, and even suggesting they would have paid good money for such a thing. "I was certainly having a good time working on and playing Spelunky, but it didn't occur to me that it was something people would pay for," Yu recalls. "For me, it was a side project."

Spelunky tasks you with mining for gold and evading all manner of hideous traps and baddies in a huge network of caves. Each level is generated by the game on the fly, meaning you'll never traverse the same environment twice. This unpredictability means that beating the game isn't a case of learning the levels; it means learning the vast array of complex and unexpected rules. Surprises lurk in every new playthrough. Some side project.

But even after Spelunky began to receive attention in the gaming press, Yu never considered it a game he wanted to charge for - partly because of its simple, pixellated presentation, but partly because he didn't want to limit his audience. "I was just happy people thought it was cool and were spreading it around," he says.

It was only when Braid developer Jonathan Blow put Yu in contact with Microsoft that the idea of a remastered commercial version of Spelunky formed. "It's definitely not something that happens every day," says Yu of his change of mind. "I thought it was worth a shot." Spelunky HD, as it is dubbed, features revised graphics and audio, as well as a variety of added extras that weren't available in the already exhaustive original.

Now with multiple commercial titles to his name, Yu could easily decide not to release anything more for free. And yet, it seems, he's still on the lookout for opportunities to do so.

"It's very nice to make a living off your games, but first and foremost you just want to create things that bring you and other people pleasure," he says. "I'm lucky. I had the chance to sell my own game, and it made me enough so I could release another game for free. Now, that game's given me a chance to do it all over again."

Christine Love, too, is eager to release more free games - although she's recently crossed the border into commercial game development as well. "There's always room for games that are too crazy or weird to try selling," she explains, "and obviously, free has a way better reach. I think being able to balance that is the real key. It's always good to be able to pay my rent, and if I can do that by making games instead of a crappy jay job, it means I'll have more time to spend making weird small things for free, too."

Some developers, of course, aren't yet industry professionals. But there are certainly those who aspire to be, and who are taking the steps to reach that goal. The DigiPen Institute of Technology is a Washington-based higher education establishment with a focus on game development, and it encourages its students to release their playable coursework into the wild.

In these cases, developers don't have the choice of charging for their games: DigiPen holds the rights to everything created as part of one of its courses, so individual developers can't commercially benefit. But students always have the option of continuing work on their projects after graduation, and they can do what they like with a redrafted version.

One of the more impressive works to come out of DigiPen recently is Nitronic Rush, a high-octane, gravity-flipping racing game with all the presentational values of a major multi-format release. "We wanted to make something really epic," says executive producer and programmer Kyle Holdwick, "so we decided to start early." In the end, it took 11 students 17 months to complete the project.

With great coverage in the press, as well as a couple of honourable mentions at this year's IGF awards, the Nitronic Rush team members are poised to take their first steps into the games industry proper. While Team Nitronic existed in its entirety for the purpose of this project alone, and some of its members are still working on other student projects, several team members already plan to work together on a commercial game. The future certainly looks bright for this band of students.

And yet, the potential for career success seems to play second fiddle once again to their love of videogames. The team plans to continue updating Nitronic Rush for free, and its members seem convinced that the continuing availability of free releases is crucial for gaming.

"Nothing makes us happier than to see our players enjoying the game," enthuses audio director Jordan Hemenway. "We've been so happy to receive all of the kind emails and tweets since the game's launch."

"I think that, in many cases, developers have a drive to create things out of pure passion," adds Holdwick. "They just simply enjoy working on games, and don't feel they need to sell them to be happy." There's something to be said about developers giving their games away as a gift to the industry and all the joy it brings, he says. The more people who can experience that joy, the better.

"Even if you don't charge anything for a game, you get so much in return," says Derek Yu. "People play it and give you feedback about it. And if you made something interesting, you might even inspire other developers."

There are many reasons people might give away their games for free - exposure, experience, the avoidance of industry pressure - but the central theme seems to be an undying love of gaming, and the overwhelming desire to bring happiness into people's lives. It might sound like a ham-fisted parable, but it rings true.

"I don't think I could really begin to explain it, but I'm glad the drive exists," says Christine Love. "I don't think I would ever have gotten into videogames at all if everything worthwhile had a price barrier to it." While Love admits she's no longer struggling to get by, she says she still empathises with those for whom buying a new game is a frustratingly rare treat - and it's those people she wants to reach.

"Buying games can be a luxury when you're more concerned about trying to scrape by enough for the month's groceries," she says. "It would suck a whole lot if the best of the medium was only available to the well-off, or people technically adept enough to pirate. Videogames absolutely should be accessible - and making them free is a part of that."