Sniper Elite 3 is an unspectacular and shamelessly entertaining sequel

Loud-quiet-loud.

Sometimes, game demonstrations are like the oddest school assembly you've ever attended. It's not just the awkward show-and-tell nature, but those strange special guests who are carted on-stage with a slight pang of confusion glistening behind their eyes. Ringo, Paul and whichever NBA star had to take to an E3 stage in the wake of a live beat poetry performance aren't the only ones. I'll never forget the time Brothers in Arms decided to herald its recreation of WW2's Operation Market Garden by getting a veteran of the campaign to relive his own experiences through the alien medium of an Xbox controller. It wasn't a pretty sight.

Or the time last week when Rebellion fronted its reveal of Sniper Elite 3, the latest in its fast-growing series of period stealth shooters, with a long, detailed talk by a real-life, fully trained sniper. We couldn't take his name, nor take photos that would compromise his identity, but we were allowed to ask questions of a man who proudly had never really played a video game until being ushered into the Oxford studio for this performance. Turns out he's been trained to kill, but he's not so hot on more serious matters like what resolution the game he's pimping will run at on next-gen hardware (it's 720p on older hardware, and 1080p on the new generation, if you're curious).

It's an odd one, because in their brief lifespan the Sniper Elite games have never really been noted for their authenticity. Recently, they've become renowned as the go-to place if you want to offload a .50 slug into a Nazi's nutsack and witness, in glorious detail, the hideous results. "What we try to do with the Sniper Elite series, we're gamifying a historical situation," Rebellion's founder and CEO Jason Kingsley tells us after the demo. He's a chap who knows a thing or two about historical recreation, given that he spends his weekends in a full suit of armour jousting on horseback and has been asked to play Henry Tudor in two recent documentaries. "We're trying to get a balance between historical realism and the shocking nature of what a sniper does. Snipers are disliked by their own side - so you're kind of an anti-hero."

It's that sense of being the anti-hero that Rebellion attributes part of the success of the Sniper series to. That kill-cam, which slows down time and gives the player an X-ray view of the damage they've dealt, probably helps a little bit too. "It's one of the challenges," Kingsley says of how Sniper Elite's most notorious mode doesn't perhaps square with an idea of authenticity. "It's got even worse for Sniper Elite 3, and sometimes it's quite shocking. But we are going for some historical accuracy. It's a bit like a F1 game - you can't actually drive an F1 car with a pad or a keyboard, and only very specialist people can do it, so you've got to give people the feeling for what it's like. But also it's entertainment."

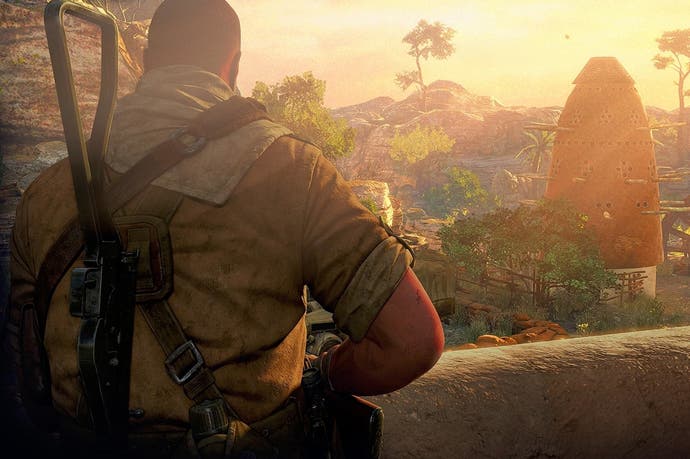

Sniper Elite 3, a relatively quickly turned around sequel to 2012's surprise hit, is certainly entertaining. It deals in schlocky kicks draped across a thin historical frame. Moving on from the destroyed Berlin that served as the foundation for the last outing, Sniper Elite 3 finds itself in the relative wilds of north-west Africa, an area of conflict in WW2 that's been largely untapped by video games. We're shown a level set in the Halfaya Pass, in the shadow of an escarpment that sits between the border of Libya and Egypt. The claustrophobia of a rubble-strewn city is swapped out for the isolation of a wider, more open map (some three times bigger than the ones it succeeds, according to a handy comparison chart whisked out by Rebellion).

More open levels mean more open routes and, the theory goes, more open-ended encounters. That's played out in what we see, anyway, which takes the loud-quiet-loud dynamic of The Pixies and stretches it across 20 minutes of straightforward stealth and gunplay. Our sniper sneaks his way past MG42 nests and high-up gun-towers, funnelling himself through a gulley in order to pick each enemy off one by one and secure a decent vantage point to scour for more threats.

It's a little like a discount Splinter Cell in period garb, but Sniper Elite has always possessed a fair sense of its own place in the world, as well as a handful of its own ideas. Some of them aren't particularly novel - there's a worrying amount of time in the presentation given over to explaining how the rechargeable health system of V2 is no more, and what the exact benefits of health packs and a staged life-bar are - while some are delightfully eccentric. The kill-cam that greets a successful sniper shot now replicates the muscular and circulatory systems of the prey, making for stickier murders, and the extra detail has been extended to vehicle takedowns too. If you've got a vendetta against a van, you can now chip away at the grill to clear a shot at the engine, its destruction told in a spectacular cutaway that sees flames bursting out beneath the hood.

Some ideas work wonderfully within Sniper Elite's world, too. Sound-masking sees you sabotaging generators to get them to cough and splutter, with each noisy outburst the perfect foil for a quick sniper shot. It's a neat fold in the rhythm of Sniper Elite's levels, and one of the advances in the third game is how that rhythm can now be interrupted or restored with relative ease, making for a game that's readier to adapt to your fumblings than previous entries.

It's nothing you won't have seen before, and the numbers that Rebellion shows off as the demo ends have a certain quaintness to them. The campaign's 12 hours now instead of the previous eight, refined multiplayer and co-op are available out of the box and the single-player maps - that are some three times bigger, don't forget - can now host 30 AI enemies as opposed to the eight last time out. There's something slightly old-fashioned about it all, though it's most definitely preferable to being drowned in buzzwords, hollow promises and a dripfeed of 'vidocs'. It's a spirit that runs through Sniper Elite 3 itself, really, a game that's traditional, unspectacular and direct. There's a certain nobility in that.