Sludge Life 2 review - more sly greatness from the masters of the compact open-worlder

Storktalk.

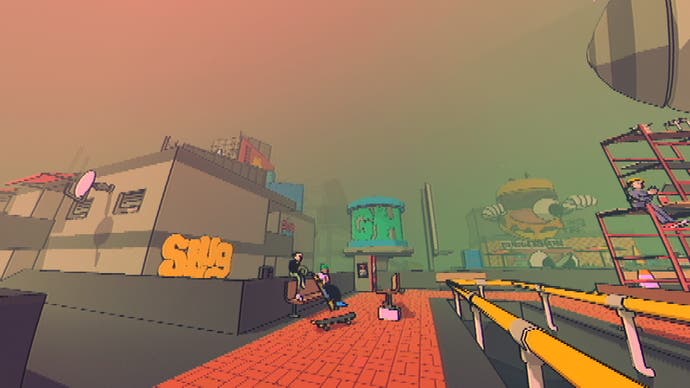

It took me a long time to realise that Sludge Life 2 is a diorama. And, wait! So was the first game! These sun-faded, intricate, often queasy worlds that you scramble your way through, part puzzle, part gymnasium, part treasure hunt, these worlds that see you jumping, climbing, leaving a sheen of spraypaint behind you? The only thing that really moves inside these worlds is the player. Yes, there are a handful of very slight exceptions to this, but they're rare and also spoilers, things you'd want to find for yourself. For the most part, Sludge Life 2, like Sludge Life before it, is a single moment captured in all its brisk human complexity. It's a place, but it's often also an instant in time. We're just jumping around and tagging walls inside it.

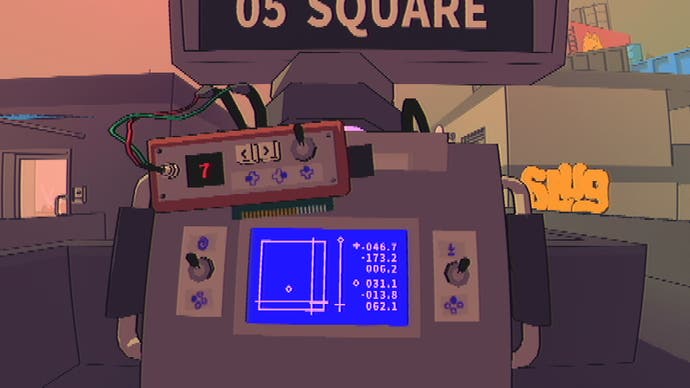

It was hard to see this at first, I think, because for all their stillness, the Sludge Life games are simultaneously defined by a frantic sense of movement. There's the stripped-back first-person parkour at the heart of it, obviously, which turns each building into a climbing frame of ledges and pipes and mini-roofs. But there's also that fisheye viewpoint that frames everything, complete with videotape artifacting and strobing noise. It makes your surroundings seem fidgety, liquid and mobile. You shift a millimetre and the world squirms to show you the new perspective. The walls are alive. It all feels weirdly intestinal, the first-person game camera as a form of peristalsis. How are we headed into this halted world? We're riding an endoscope. Open up! Say ahhh!

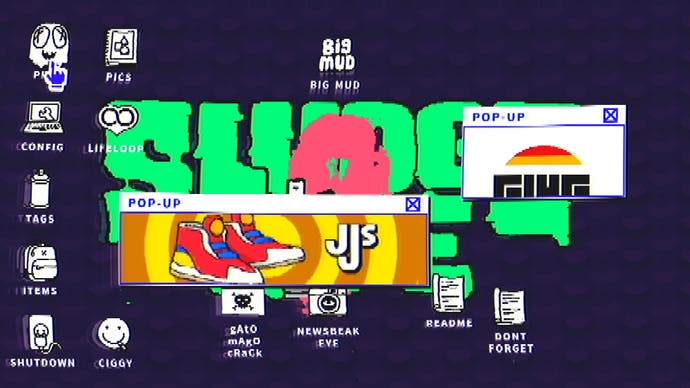

Sludge Life 2 is very similar to the first game in this, and almost all, respects. And that's a good thing. These are compact worlds, but also worlds I never feel I can get absolutely everything out of. There's that glint of paradox throughout. You load into these games through a beautifully realised operating system, and the sense, from the off, is that there are secrets everywhere. There's a sense of rules being broken, even though in some ways these are games that deal with classic ideas of exploration, narrative, traversal, puzzling and collecting stuff. These are angry games, but they never let the anger define the experience. There's tons of craft and storytelling, but you are free to make of it what you will.

Anyway! Sludge Life 2 begins in an empty hotel bathtub, as all post-hangover narratives should. Your job is to track down Big Mud, a friend and colleague, who has gone missing on the eve of their big break, following a truly colossal bender. As with the first game, this tracking down involves heading out and exploring a compact open-world of questionable fast food joints, gantries, faded public spaces and shipping-container architecture, all suspended over a toxic swamp, and with the horizon dithered away by lurid smog. You run and jump and climb. When there are graffiti spots you tag them. When there are people, you hear what they have to say.

As it goes with sequels, it's all bigger and more complex than the first game spatially, but confidence and tone of voice was never a problem with this series, so Sludge Life 2 can build on existing strengths rather than having to reinvent much. It helps that the new playground you're loose in is absolutely glorious, fanning out from a multi-story hotel where superficial luxury has long-since given way to grimness and toil. Various bellhops are scattered around the place, trapped under luggage or caught in elevator doors. Cleaners mutter as they send antique vacuum cleaners wheezing over antique carpet. Other staff are often found in informal break spaces behind the spots where they technically work, having crafty cigarettes or staring into space. Every job here is ultimately meaningless or impossible, and what dignity there is comes from the manner in which you resist it.

The hotel's wonderfully complex, absolutely teetering with things to find and narrative threads to follow. There's Big Mud, sure, but what's with the cats who have staked out their own hotel suite? How do I get onto Floor Five, which seems otherwise inaccessible? Why's the lift broken and what lies at the very top of the space? What, for that matter, lies at the very bottom?

The moment-to-moment missions are what you want them to be, then. And the hotel's just one of many locations, all of them simultaneously colourful and faded, riddled with dereliction and disappointment and moments of beauty - little human vignettes - to uncover. It's narrative hide-and-seek. Someone's fallen out with their boss and is willing to give away a secret. Someone's growing something they don't want anybody to know about. In one restaurant, sad burgers burn on a flat top while, round the corner, the two chefs make out in a quiet spot. Sludge Life 2 is like this wherever you look. It's filled with little instances that make me feel like I'm a 19-year-old dishwasher again, being paid £2.40 to scrub pots and sit on plastic lawn furniture playing endless rounds of Solitaire. It's honest about what this life is like, but it also finds moments that make you want to cheer. Everything can be subverted, can't it? Can't it?

Leading you through all this is some of the best and cleanest post-Ubi open-world stuff I have ever seen. There's a number of clear paths through the game just marked by the pull to acquire things from the landscape you're jumping around on, and yet it never feels like empty busywork. Hit all the graffiti tags. Collect all the gadgets. Open up - a great place to start - all the fast-travel spots, which becomes a series of puzzles in itself as you lay a purposefully uninformative map over your own experience of the landscape. But also: find all the other graffiti artists, collect the tapes, take a series of meaningful photos.

This is enough. This, with the quest to find Big Mud, is enough to lead you through a land of wit and distractions, of grimness and cigarette mascots and disillusioned cinema staff and talking pigeons, but also of joy. The joy of movement, mantling and dropping through gaps. The joy of working things out, of making progress, and of not making progress. The joy of finding a perfect spot to rest, and to become, briefly, one of the diorama people scattered artfully around you.

Sludge Life games are their own thing, a cocktail, I suspect, that has different components depending on your own background. To me they're hip-hop mixtapes passed from friend to friend, blended with underworld comics and stickers and those weird shows that the TV channels used to show really late at night. They're things I wished I was cool enough, smart enough, to be a part of.

But these games, the more I play, also form meaningful, illuminating links with other games. Ubi open-worlders, sure, although they walk the line between expert distillation and open parody really well. But also stuff like Gravity Bone, which gives you a curated glimpse of one aspect of a personal landscape that feels utterly imagined and coherent. And games like Umurangi Generation, whose developer is thanked in the end credits: another game about movement and stillness, generously opening up a world of experience for players to explore.

Last night I loaded Sludge Life 2 up again to take some screenshots, two of the game's endings witnessed, and a few items still out of reach. Past the OS with its pop-ups and scattered folders, into the game and then across the map via those brilliant sharp, instantaneous atomiser blasts of fast-travel transporters. Back into the hotel where everything started, and where every room, I now discovered, had its own little diorama waiting behind the door.

Here was a man asleep on a bed, snoring as the radio played. Here was a dog watching television by themselves. Here was a mountain of kitty litter in a bathtub. Here was a person sat glumly on a chair with one of those Venetian pet collars around their head. Here was...

That's it, isn't it? Stepping out into the corridor at one point I realised that the doors went on as far as I could see, and then stairs and more floors, more doors, more glimpses of this fascinating and playful place. The diorama spills out of the windows and off into the distance. Who knows where, in the mist and murk, it finally draws a boundary.