Skald: Against the Black Priory review - a robust but inessential throwback to the RPG's primordial era

Blue cloister cult.

Skald: Against the Black Priory is without question the retro-est game I have played. The recent spate of boomer shooters and PS1-era survival horrors are mere whippersnappers in this 8-bit RPGs eyes, cosplay Roman soldiers marching under the shadows of its artificially ancient Pyramids. High North Studios dark fantasy adventure is a devoted recreation of role-playing from the primordial days of home computing. If it threw back much further, you'd need to visit a university to play it.

Skald is a good game. I want to say that up front and unambiguously. It's a tightly crafted, moodily written RPG that makes atmospheric use of its Commodore 64 aesthetic. But it also had me questioning the value of digging up this part of the past, as Skald's self-imposed restrictions make it tough to recommend in a genre that has burned so brightly in recent years.

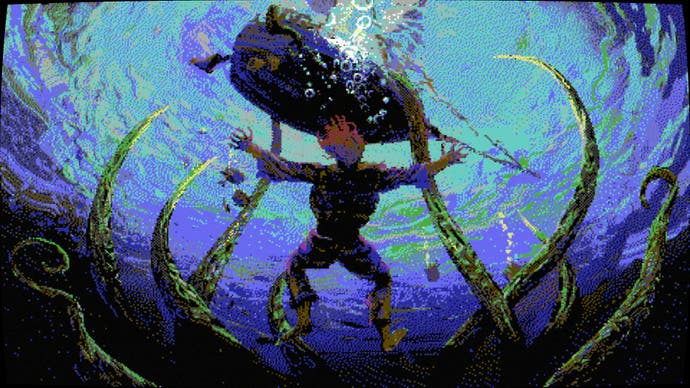

We'll get to that in time. For now, there's a ship to wreck. Skald's adventure kicks off in enjoyably immediate fashion, with the vessel your character is travelling on being bisected by some giant, betentacled sea monster. As you drift down into the abyss, the story flashes back to the journey's inciting event; an aristocratic former friend of your father's asks you to find his daughter – a woman named Embla – who has absconded to the Outer Isles for reasons unknown. Then the abyss spits you back out onto the shores of one of these islands, where it soon becomes apparent that Strange Happenings are afoot.

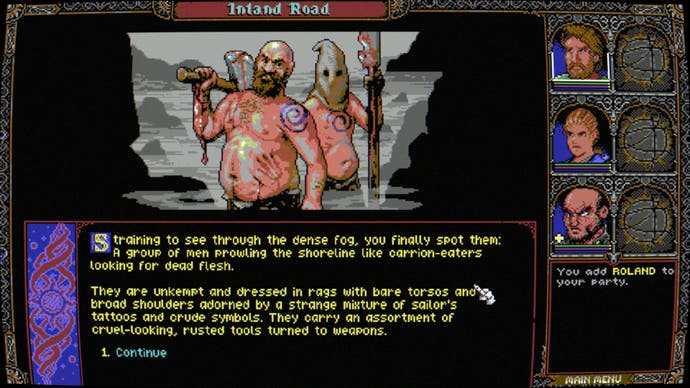

Skald's Sword & Sorcery tale communicates like a knife in the dark, straight to the point and nasty as hell. As your bedraggled character hops across the pebbly coast, you battle ship rats and scuttling crabs horribly mutated by some unseen force, and pass the smashed corpses of sailors pulped by the roiling tide. The first NPC you encounter is a haggard old hermit who makes his living by picking clean the bodies of ill-fated seamen. The first side-quest you receive involves descending into the well of an elderly farmwoman to retrieve the bones of her children.

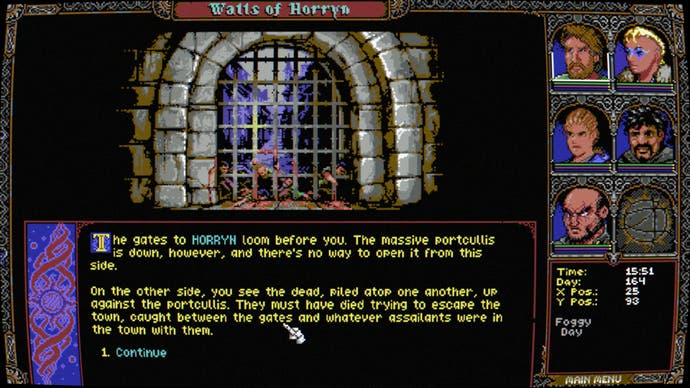

It's as clear in its vision as it is dark, and by far my favourite thing about Skald is how it uses the visual and audio stylings of the Commodore 64 to elevate this atmosphere of eeriness and dread. The garish 8-bit colours heighten the caricature-esque character art. The pulsing, buzzing soundtrack rubs like sandpaper against your nerves. The dithered pixel art pressed against the inky black background oozes with grim personality. When you enter the town of Horryn, for example, the scenes of devastation are only made more vivid in how the art abstracts it.

The broader mystery that emerges from this horror is dramatic and entertaining, though it lost me a little when I realised it was drawing heavily upon Lovecraftian archetypes. I liked Lovecraft as a teenager, and I learned a lot of fun new words reading his work (as well as some less fun ones). But putting aside the fact that Lovecraft was a colossal racist and, when it comes down to it, not a particularly good writer, video games have stripped that literary field of all and any fertility. Lovecraft isn't weird anymore, folks! Other cults are available! There's nothing more deflating when you posit a grand and spooky conspiracy, only for the answer to be 'oops we woke up some fish-people'.

Fortunately, the Lovecraftian elements are only a part of Skald rather than the whole, and the game interweaves these tired tropes into its own, more intriguing lore. For the most part, the story presses inexorably forward, though there are usually several smaller distractions to pursue in every location you visit, alongside a few bigger side quests such as an extended foray through a mage's tower. Likewise, the characters you encounter are vibrantly written, but don't expect to get to know your party enormously well. Like your own character, your companions are there to do a job, and they don't stray too far from familiar RPG archetypes. The noble cleric, the grizzled mercenary, the roguish pirate, etc.

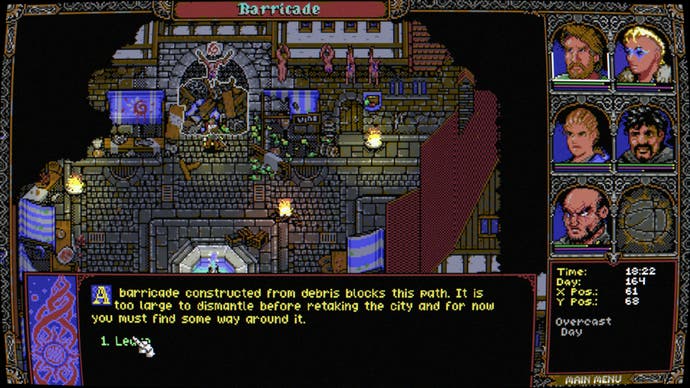

Mechanically, Skald is an unapologetically traditional RPG, mixing top-down exploration of both a larger overworld and more specific locations, with some text adventure-style dungeon crawling and turn-based combat. It doesn't control like a trad RPG, however, using a modern, mouse-based interface that's intuitive and easy to navigate (although the game does support an option for a more classical UI).

Given the condensed nature of the game world, exploration is fairly rewarding. Locations are filled with lootable items, secrets that can be revealed by characters with high awareness, and food items that you cook into nourishing recipes for your camp when you rest. It also features obligatory 'Go West'- style text mazes, though mercifully the developers don't overload the game with them.

I was less thrilled by Skald's combat. Battles are surprisingly evocative considering how visually simple Skald is, thanks in no small part to some gnarly sound effects for blades cleaving through flesh. Also, the Victory screen music is fantastic, a grungy, synthy earworm that's been playing in my head for the last few days.

From a more tactical perspective, Skald does reward careful assembly of your party. Mine revolved heavily around the enormous damage dealt by Roland – the aforementioned grizzled mercenary, who I specialised in two-handed axe wielding. Nearly everyone else fell into supporting roles. My cleric would heal him. My mage would blind and bewilder other enemies until Roland could get around to them, and my custom-made Officer character would provide partywide boosts to movement and defence.

By the time I approached the Skald's end, however, I'd grown weary of fighting. Skald places significant emphasis on character positioning. Both party members and enemies will block the path of other characters, and you can't attack an enemy from a diagonal position, only from the four points of the compass. In and of itself, this isn't too much of a problem (although navigating rogue characters so they can backstab enemies is as much a pain in the bum for you as your foe). But aside from the fact many encounters take place in incredibly cramped arenas and corridors, battlefields are often littered with tiles your characters cannot walk on, and the simple graphics and perspective make it hard to parse what is a viable movement space for your character and what isn't. Hence, too often the challenge is in where you can and can't move, rather than what kinds of enemies you're facing. It doesn't help that too many fights involve battling rats, bats, giant insects, amorphous blobs, or similarly unimaginative foes.

Alongside these harder problems is that question – what exactly does Skald bring back from the nostalgia mine? For context, I'm a big fan of retro-shooters, but the reason I like them is not just because I grew up in the 90s and have a weird gore fixation. It's because they reinstate ideas of design, particularly level design, that modern shooters have for the most part lost interest in. Each of them plays with 3D space in imaginative ways unique to its designer, and they demonstrate how much potential remains in that style of virtual architecture.

There are examples of this retrieving of lost design ideas in the RPG space too. Baldur's Gate 3 is essentially a modern Ultima, taking that "anything goes" style of RPG design and spinning it out to its logical extreme. That's an unreasonable game to compare Skald to, however, so a fairer example would be Legend of Grimrock, which resurrects the old-school 3D dungeon crawler. That's a highly specific style of RPG, with unique game mechanics, level and puzzle design that were lost to time. In bringing them back, Legend of Grimrock demonstrated the specific appeal of that design, and showed how it can be explored in new ways.

I'm not sure that Skald can make the same claim, because it's drawing from an era where the big innovation was simply getting an RPG to work on a computer. It replicates that era well, but that also prevents it from bringing much to the table that you can't get from other, frankly better RPGs. Its most distinctive quality is how it uses its 8-bit aesthetic to create a moody, dark fantasy world, which it does effectively and, for the most part, enjoyably. But is that enough for me to declare Skald a game you must play? Ultimately, no.

Then again, if you have exhausted the higher echelons of fantasy RPGs, then there is an adventure worth having here, doubly so if you hold a candle for the Commodore 64. Skald might pray to the blighted altar of Lovecraft, but it has more in common with the work of Robert E. Howard, a grisly, propulsive fantasy adventure unpretentious in its aspirations and unyielding in its focus. Its ideas might not be especially radical, but they are the foundation upon which entire worlds were built, and in returning to them, Skald proves those foundations to be as robust as ever.

A copy of Skald: Against the Black Priory was provided for review by Raw Fury.