Out Ran: Meeting Yu Suzuki, Sega's original outsider

Exploring the magic, music and making of the Sega legend's racing games.

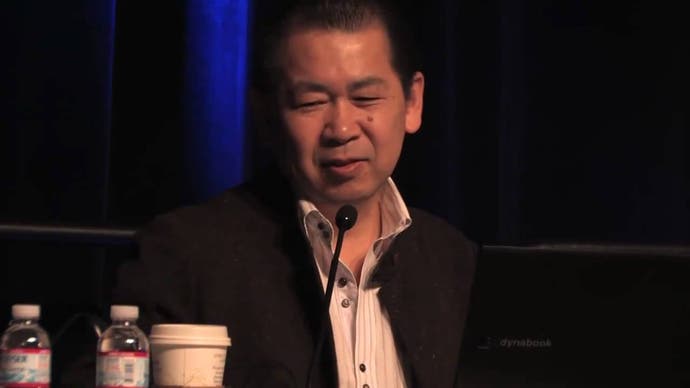

Even during the height of his fame at Sega in the 90s, Yu Suzuki was an outsider. Unable and unwilling to keep to the 8.30am starts demanded by the company, Suzuki moved his team out to a rented office near the main headquarters so he could keep his own hours. Sega colleagues would joke that the name of Suzuki's group - AM2 - came from the fact that the only time of day you could guarantee all the team would be working was two o'clock in the morning.

I got to meet Suzuki early last year, at a time when he's even more of an outsider to an industry he's been so instrumental in shaping. Our time together was short (I don't think any amount of time in his company is adequate to cover the significance of his achievements) and occasionally stilted - the interview was translated by his eldest daughter and personal assistant Nanami, who's learning English with his encouragement.

Yu Suzuki has spoken at length about his most beloved creation, Shenmue, and has said all he possibly can about what's going on with the much requested third instalment, so it made sense to filter our brief discussion through his work with driving games and his philosophy of design - one that, I've always thought, carries a beautiful simplicity - from the three-button input of Virtua Fighter through to the uncomplicated pleasure of cruising through Out Run's branching courses.

It's a philosophy born of Suzuki's own modesty. He's aware of the impact he's had on games, as well as on the people who've played them, though at times it's as if he's almost embarrassed by the adulation that comes his way. There's no mystery and no pretension to his games: they're just the product of an engineer's eye, a perfectionist streak and what happens when a designer is given the opportunity to indulge their own passions.

"The reason I started making games is I joined a game company," Suzuki says, his bluntness softened by a smile that lights the room. "That's it! It's not like I wanted to be a game designer. I just entered the game company. I usually don't play video games. For example, with driving games - I've got much more interest in real cars. That's the reason I went for that style.

"As a student I was looking for a good company, and looking at which company has a good future - and the software companies, that looked good. Games, they don't matter so much to me. I saw a challenge at Sega, Fujitsu - a computer systems company, not a game company - I visited them all. Sega's people, though, were the most interesting people."

Suzuki joined Sega in 1983, his first project, Champion Boxing, a simple arcade game that would also find its way to the SG-1000, Sega's first home console. His next projects, though, would allow him to flex the knowledge he'd acquired while studying computer programming at the Okayama University of Science. "From the very beginning I wanted to create a 3D game," he says. "At university, I was studying how to make a 3D house. So at Sega, of course I wanted to make a 3D game."

3D technology wasn't so readily available in the mid-80s, so Sega and Suzuki had to fake it. The Super Scaler engine, itself an extension of the VCO Object system that powered the quietly influential Buck Rogers Planet of Zoom, made its impressive debut with 1985's Hang-On. Suzuki's designs for the game were all conceived in 3D, before being reverse-engineered to work in two dimensions. The first game of Suzuki's to gain wide acclaim, it also allowed him to explore his first love.

"I adore bikes. Mostly, off-road bikes - like motocross, enduro racers, Paris Dakar. But, I was researching bike races, why they're popular. The end result was [Hang-On's] on-board bike."

During Suzuki's research, the world of motorcycle racing was being shaken by Freddie Spencer, a rider from Louisiana who, in 1983 at the age of 21, became the youngest person to to win the world championship. The record was broken by Marc Marquez a couple of years back, and the riders both share an elbows-out extravagance on the bike that wowed fans.

"Freddie Spencer's riding style, it was so nice," says Suzuki. "And my game was like a homage. That's the reason I wanted to make it - Freddie Spencer, he rode a Honda bike, and I loved the way he hung on!"

Hang-On itself remains a technical marvel, its sense of speed still strong enough to turn the stomach today, but what really helped sell it at the time was the cabinet. Basic versions featured a handlebar and levers, but the full-on deluxe version starred a full replica of a 500cc road-racing bike, inviting players to lean in emulation of Spencer's real-life knee-scraping heroics.

"At that time, to that point, game machines, they were like table-tops," says Suzuki. "This cabinet type, it was really unusual. Unusual is good - it's a good thing to market. It's good commercially. That cabinet - it was a result of fast planning, and because I like Freddie Spencer. I wanted to simulate Freddie Spencer, and Freddie Spencer's bike."

Suzuki had even grander plans for the Hang-On cabinet - initially, it was going to feature a gyroscope that would simulate the acceleration and deceleration of riding a motorbike at speed, a concept that would be ditched - "the cost increased" says Suzuki, "and at that time, Sega people, they said that idea's wrong" - before being returned to for the ludicrously extravagant R-360 cabinet. It's a glorious creation, able to spin players around in a servo-powered loop, but it wasn't without its own dangers; during testing of the cabinet, Suzuki once recalled, a Sega employee was left suspended upside down in a malfunctioning pre-production unit overnight while their colleagues marvelled at their new creation.

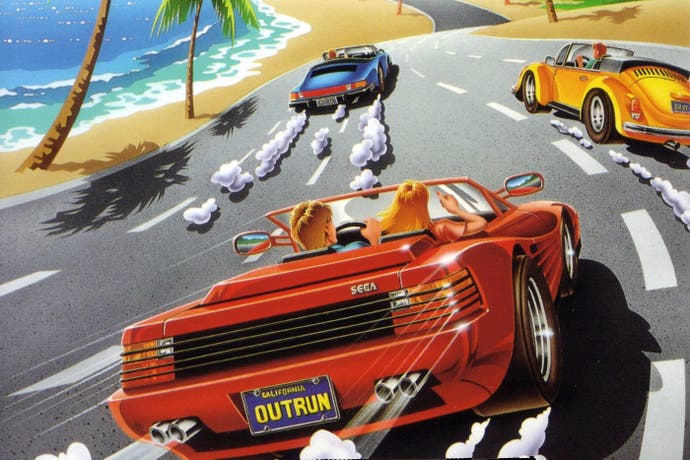

AM2 and Suzuki's next game was arguably their greatest. Out Run, released towards the end of 1986, is remembered for many reasons: its iconic music, and its totemic status as all that was great and cool about Sega and, indeed, video games of the 1980s. Perhaps its finest achievement, though, was in how it was one of the first and still one of the very few games in its genre to forgo the thrill of racing for the sheer pleasure of driving.

It's the ultimate celebration of the open road - of reading the undulations and swerves of the asphalt as it hits the horizon, and of simply savouring the sun as it hits the windscreen and the breeze as it whistles though the windows. Out Run's a love letter to the automotive journey that's born out of experience.

"The main inspiration was originally The Cannonball Run," says Suzuki. "It's an American movie - it's about racing, it's really funny. I was going to do a trip along the same coast - from Los Angeles through to Miami. But some guy, he told me the American landscape, it doesn't really change. So then, I changed - and went to Europe. I started in Frankfurt, then Monaco - the F1 course! - and then Switzerland and Rome."

The ever-changing landscape is captured, via a sunnily optimistic and pixellated filter, in Out Run's ever-changing courses, where tulip fields run through to elegantly crumbling seaside resorts and through to cloud-covered highland passes. Suzuki's own ride for the trip wasn't so glamorous - a BMW 520, a four-door rep mobile that doesn't quite stir the soul like the car that would eventually star in Sega's game.

"It took two weeks for the trip, and the trunk was so small," says Suzuki. "This BMW, the top-speed was only 200km/h. It's not so fast - a Porsche or Ferrari would have been much better!"

Suzuki would come across more inspirational rides during his journey. On the stopover in Monaco, where the gilded streets always act as a showcase for the latest supercars, he spotted a Testarossa, Ferrari's then-new flagship car whose wedge shape accommodated a tuneful flat-12 engine. The designer was smitten, returning to Japan determined to make the car the star of his latest game - even if it took him some weeks to find a model in Japan, squeezing his team into a smaller, less stirring car for a cross-country trip to photograph a Testarossa for reference.

Out Run's a classic that's no less thrilling to play today than it was just under 30 years ago, something which is easier to do than ever thanks to the recent 3DS port - another in a long line of restorations from developer M2, and just as exacting and exciting a recreation of the original experience as all the work the studio has done before. The newer version manages to finish off some of the work Suzuki was unable to - he'd always intended for there to be a selection of cars, a feature gradually unlocked in M2's version.

Even away from the flourishes added in the 3DS port (you can unlock an unadulterated emulation of the arcade original in the newest version) there's a magic to Out Run the years haven't dimmed. The simplicity that's core to Suzuki's design masks a more complex centre: in Virtua Fighter it was strings of combinations fuelling a fighting system that beautifully interlocks, and here it's a handling model that, despite its naivety, has depth. Tires squeal their way towards the edge of adhesion before fading away, and the satisfaction of slamming down the transmission and engine braking is something you'll find in few other subsequent driving games.

There's a rhythm to Out Run, too, that's timeless. Suzuki's long-time collaborator Hiroshi Kawaguchi is largely responsible of course, famed for his soundtrack compositions that are so perfectly evocative of near-endless summer afternoons and impossibly orange sunsets, but Suzuki deserves some credit himself. An accomplished guitar player, there's a musical cadence in the layout of each course, a backbeat of speed that flows through them before they crescendo with switchbacks and heart-skipping dips. When consulting on Sumo Digital's port of Out Run 2, I've heard that Suzuki would impart the importance of music when advising the designers, stressing the tempo of each turn.

Just as important to Suzuki's vision, and to his design, is technology. His greatest works came at a time when software design would happen in tandem with hardware design, and Suzuki often oversaw the two strands - most famously as he helped Sega's move into full 3D worlds with Virtua Fighter, a series that was born from the animations of the pit-crew in its predecessor Virtua Racing. How important is technology to Suzuki's own design outlook?

"Game history, it's not so big," he says. "Games are based on computer technology, and the hardware is getting better and better - always I had to look at the hardware technology. Hardware innovation and driver software technology are important, but I think a good balanced game is the most important point."

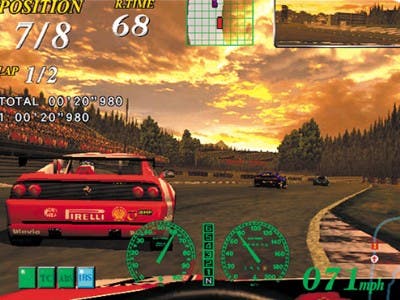

Suzuki never really turned his back on his love of cars. Later in his career he channelled it into F355 Challenge, one of the purest expressions of passion for the Scuderia ever committed, its laser focus on replicating a single car's characteristics foreshadowing the sim market that flourishes today.

"F355, the concept was a bit different," Suzuki says. "F355, I think, it's not a game. It's a driving simulation system. This time I had the same car - the F355 - and I have many friends who are racing drivers in Japan. Sometimes I would go and learn the circuits. I had to set the performance logging system, and I used my car to get some data - some key data, like braking data. I'd get my data, then I'd get the professional's data. That's how I made F355. The Ferrari people really liked the game - now, there's one in the Ferrari museum."

I wonder if Suzuki's ever had a chance to reflect on the impact he's had on the genre, and if he ever dips back behind a virtual wheel with contemporary driving games.

"I really like the real ones, not the games! Last year, I drove a Ferrari 458 in France. It was really impressive. That's the best Ferrari, for me! It was amazing. I usually don't play games. I only really play games with my second daughter - she likes puzzle games." 30 years on from when Suzuki first made his name with Hang-On, it seems even his thirst for speed has mellowed. "Five years ago, I had 6 bikes - a Ducati, a Suzuki, a Haybayusa," he says. "Now, it's just one 50cc scooter. It's a step down!"

Yu Suzuki remains an outsider, even more so as his pace of life has slowed. He still seems desperately keen to make the conclusion to the Shenmue saga, his life's work, happen, but even if that never comes to pass I hope we get to play another Suzuki game soon - to sample his flair for simplicity again, and to breathe in the lungful of summer air his creations so often embody. I have so many other questions I'd like to ask him, but the timer runs down to zero before we can reach the next checkpoint.