Mask of the Rose review - kissing optional, but recommended, and tricky

Fallen in love-don.

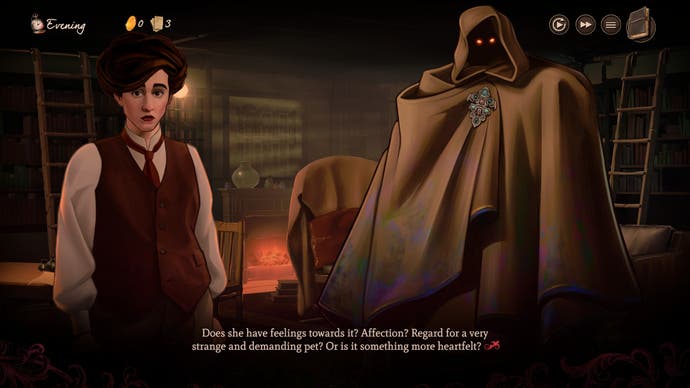

Dating sim-slash-murder mystery Mask of the Rose is an intriguing setup - but its experimental nature strains against its own structure. In the familiar-to-some setting of Fallen London, developer Failbetter's gothic world that's grown to house Sunless Sea and Sunless Skies - and the original browser game of the same name - Victorian London has only recently fallen. Its cast are all having to adjust to new ways to relate to their society, to their communities, to their belief systems, and potentially to love. Foundations are shattered - not least among them the meaning of life and death, when their new world’s first murder turns out to be an impermanent thing.

While the systems are intertwined, it's difficult not to think of the murder mystery and the dating sim as separate ideas within Mask of the Rose. The bookends of the game, the character creator and the epilogue, say 'dating sim', but it's London's mysteries that lead you through. There's far more not-romance to do than romancing - but complex relationship dynamics underpin everything. When the murder victim's sister refuses to discuss the grisly details, it isn't about our relationship, but that of the siblings. If he hasn't decided to trust me with those details yet, then she isn't going to divulge them behind his back.

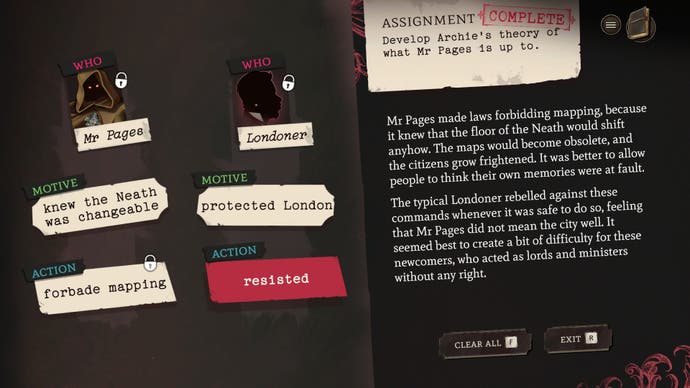

Other than showing up in places to chat, the primary way you interact with Mask of the Rose is its storycrafting system, which you're introduced to as a way to unpeel the mysterious Masters of the Bazaar's incentives. It's spiritually a notecard-and-red-thread conspiracy board, where an unknown motive - or unknown reaction - populates the world with questions to ask until you have your answer.

The same system builds into the more complex structure of the 'whodunnit' at the heart of the game - not just 'what' and 'why', but 'who' and 'how', sending you around London to ask just who would have the motive to do such a thing (surely not primary suspect and housemate Archie? Who somehow always has a crush on me even if I call his mother an interfering old bag?) As you talk to people, they provide potential prompts to add to the board, letting you refine and reiterate.

Storycrafting is fun, but it's finicky, particularly when it comes to the murder mystery. Because it's the way you add new interactions with the world - to interrogate motives, or suspects, or means - you have to stop once it's suggested something you want to explore further. Creating a new theory, or placing a new suspect on the board will populate the world with a different set of interview questions, and you can't switch back and forth. It's a shame, because it's a fun tool to move ideas around and play with the logic of it, but you can break your own investigation if you experiment too much.

Storycrafting isn't only used for mystery solving, however, as there are also templates for writing romance novels, pro-rat propaganda, and things I know I haven't even discovered yet over several playthroughs. There is an awful lot to do in Mask of the Rose, and it's not just that you can't fit it all in one playthrough - it's difficult to fit one thing in one playthrough. Over several, I think I've had one where I solved the murder 'perfectly', with all loose threads handled exactly the way I wanted them, and it was one where not only did I not manage to date anyone, I didn't even make any friends.

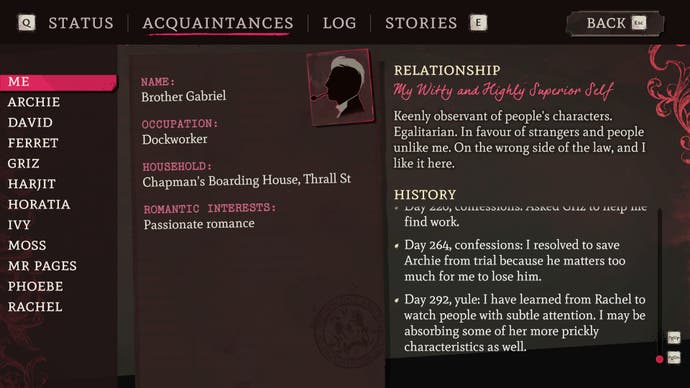

Mask of the Rose models its relationships in particular ways, where you can either befriend, seduce or romance. I appreciate this in theory - a friendship has its own vulnerability and intimacy, and not everyone sees sex and romance as intertwined - but in practice, it felt a little clunky. I was able to choose whether I was interested in sex, romance or both at the start of the game, but also individually negotiate these things whenever an individual relationship hit a questioning point. If I wanted to passionately romance someone, in the game's own language, I'd have to choose one option, and then pivot to the other.

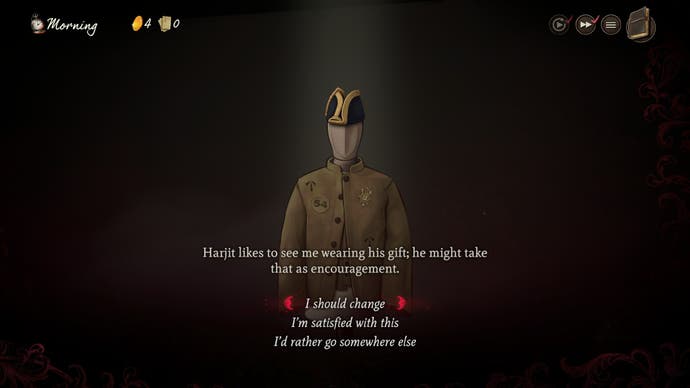

All that said, it's difficult to confidently infer some things about how Mask of the Rose intends to model its relationships at all. It's subtle, and often when I experienced friction I found myself questioning whether it was an intended behaviour, or a bug. If I tell Archie I just want to be friends, and then he later confesses his feelings to me from inside prison, is that in error, or the result of my unfailing trust in his innocence and my visible efforts to help him? Characters have things they want, qualities they'll trust, and situational context that impacts their behaviour - including your choice of hat - and these aren't all signposted.

This is additionally complicated by most of my time with the game coming before a patch that appeared to make relationships progress much more aggressively - towards both romance and hostility, potentially within the same person. Despite several playthroughs, it turns out that I likely haven't seen a complete romance route at all. I want to say that sex and romance both feel like they 'belong' to their characters. Whether sweet or suggestive, they never depart from that sense of real people negotiating their desires - connecting with another person just being one want that has to balance its place among others.

The crux of my difficulty with Mask of the Rose is that - between the plethora of options to pursue, the inscrutability of character's desires, and the brevity of the game - I don't know what it wants from me. I found that if I treated it like a conventional dating sim and tried to follow a specific character's route, sometimes it wouldn't progress for several days, or they'd insistently only see me as a friend. (Post-patch, it seemed to actively irritate my love interest of choice.) If I treated it like an RPG, and followed quests around - Can I meet everyone to fill the census? What's with the tentacle in the basement? Who killed David? - I wouldn't have time to follow any of these threads to their conclusion.

I lament this point because this friction obscures some really excellent writing. The Neath has long been a setting of Victoriana-but-wrong, exploiting the space between the familiar and not for tension and horror. In many ways, the horror is much lighter than in other Fallen London 'verse games, but in placing much more historically grounded people in its setting - for them to struggle in that space between the familiar and the not, instead of the player - its moments of pain and revelation take on new depth. When it fully unravels, the motives behind the murder are both intimately knowable and inexorably Neath-y, as Fallen London is destined to become.

Even this point comes with a caveat, though, as the more historically grounded writing takes risks. One of the character arcs revolves around Rachel, a Jewish woman, considering her affection for Milton, a devil. This being an antisemitic trope can actually be lampshaded in the game, if you propose having a fictionalised Milton as a love interest in Rachel's novel.

There are multiple ways to read this scene - as a gesture at different ideologies between modern audiences and Victorian ones, as Rachel acknowledging the optics of her own desire for Milton, as Failbetter expressing self-awareness about the trope and a desire to write it sensitively - and ultimately it isn't for me to say if it 'worked'. While I trust that Failbetter worked with consultants, this arc left me with questions.

When Mask of the Rose was announced, I don't think anyone expected that the words to describe it would be "risky" and "ambitious". It might be easier to straightforwardly like it if it were a simpler game. As it is, it feels like it's bursting at the seams - with long quest threads without enough time to pursue them, character desires so subtle that putting on a flirtatious hat may condescend, and a conspiracy board that breaks the mystery if you have too much fun with it. Its writing takes the long-familiar - and long-evolving - Neath back to its roots, with evocative, thoughtful, and flawed exploration. It's this version of the game I can't stop thinking about, however - flawed for all the same reasons it fascinates.