Turning Up The Heat: Part 1

Part one of our huge Fahrenheit interview with David Cage.

In the me-too, sequel, licensed fodder-obsessed era that we're currently stuck in, a game as ambitiously forward-looking as Fahrenheit is like a breath of cool fresh air. Abandoning the current trends and pursuing ideas that have long since been foolishly discarded by others, Quantic Dream's latest labour of love could well be the first narrative-driven title in years to reawaken the public's long dormant thirst for adventuring.

But the word 'adventure' has been thoroughly abused over recent years, used to latterly describe the increasingly marginalised 'point-and-click' style that, while fondly remembered by many, is a genre that few publishers would touch.

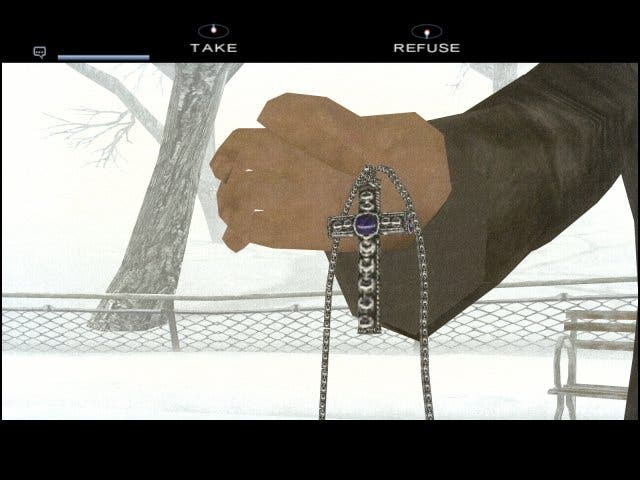

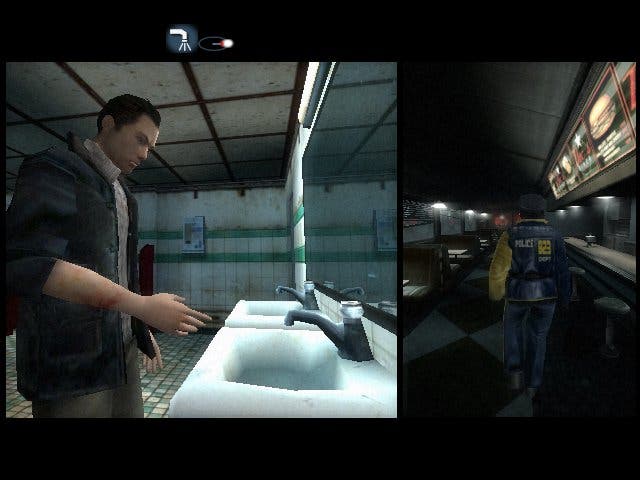

And as much as we go a bit misty-eyed when we recall the greats, the adventures of the past were often dogged by obscure puzzles, linear to a fault and inflexible. Where Fahrenheit differs is in its 'rubber band' storytelling technique that allows small choices and decisions to have consequences. Having had a taste of four of the game's 50 scenes, it's safe to say we're getting steamed up about Fahrenheit, which you can read about here.

In the meantime, we grabbed Quantic Dream's chief David Cage for a chat about this intriguing game to ask him about everything we could think of, from the storytelling, the characters to the challenges in getting publishers to take the game seriously. Check back tomorrow for the second half of his mammoth response, including details of his love for something we hold rather dear ourselves...

My name is David Cage. I am the CEO and founder of Quantic Dream. After my first game ("Omikron The Nomad Soul" featuring David Bowie), I am the writer and director of Fahrenheit.

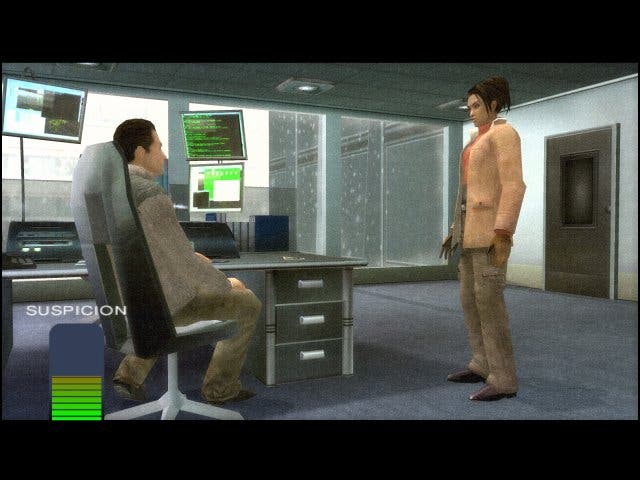

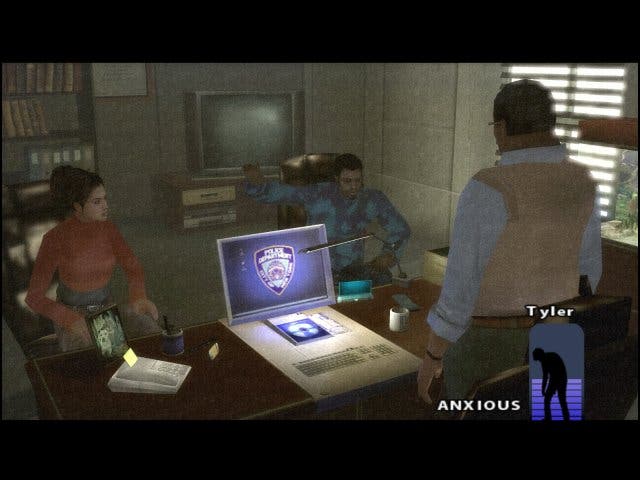

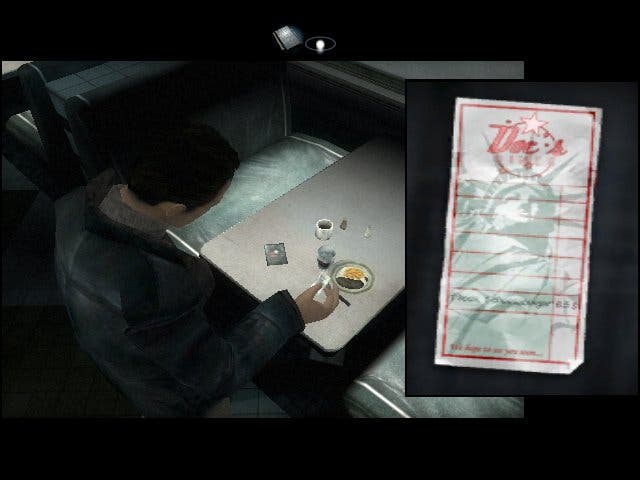

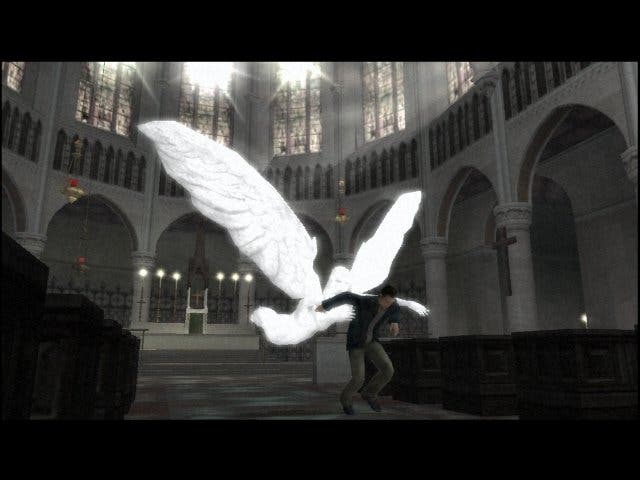

Fahrenheit is a story-driven experience, a paranormal thriller where your actions modify the story. What makes the game really unique is that the player can play with the story, almost in a physical sense. He can stretch it, deform it or twist it, depending on his actions.

I started thinking about Fahrenheit when I realised how frustrated I was about video games in general. I have played games for twenty years. I've changed over the years as I've got older, but I had the feeling that games were still exactly the same as when I was 15. Of course, technology has massively evolved over that time, but the concepts behind most games are still exactly the same. It seemed to me that technology evolved faster than ideas.

I also felt that there was a kind of general agreement about the fact that a video game should be about killing, destroying or driving. It is about creating toys for kids to play, without other creative ambition or vision.

I was also generally frustrated with narrative in games. Most games clearly seem to target ten-year-old kids. When you think about the topics, the characters or the stories told in some games, there is no possible doubt about the fact that they are aiming for young kids. But when you look at game demographics, you realise the average age of gamers is 29-years-old. It became obvious that this industry was not making games for its demographics, but only for the youngest part of it.

My last goal was narrative. When you look at the game language, you realise that it is based on repetitive patterns, a limited amount of actions that the player has to repeat with a specific timing or in different places. The reason is that the player can only access to a limited amount of actions because of the interface. This strong limitation is one of the reasons why narrative is generally so poor in games.

Another reason is clearly that no one cares about stories. No one has yet understood in this industry the power of a good story and good characters. When you talk to some publishers, they answer that what is important is not who characters are, but what they can do. This is absolutely wrong. The experience is a million times more intense if you care for the characters and if you know why you are doing something.

My thinking about narrative also included the game language. In many games, this language is only limited to a few words: fear, anger, frustration, power. When you think about movies or books, you realise that their vocabulary is infinite. They can make you go through all human emotions. So why should games limit themselves only to a couple of words?

These are just some of the many thoughts that initiated the project Fahrenheit. On top of this quite cerebral approach, there was most of all a real motivation to create an experience that would be really unique. I was dreaming of a game exploring a new direction, with more sophisticated content for an older audience, an experience that could be defined as an "Emotional Ride". This is where Fahrenheit came from.

Fahrenheit is the real title of the game. It refers to a very important character in the game: cold.

The game was renamed "Indigo Prophecy" by Atari for the US. I guess they were concerned that some people may get confused with Michael Moore's movie "Fahrenheit 9/11". This is definitely not the title I would have chosen…

With Lucas Kane, I wanted to create a hero that is just a pawn on a chessboard. All through the story, he has no real option. He has no choice than to move with the flow of his destiny. He just happened to be at the wrong place at the wrong time. He is no super hero, it could have happened to anyone, and this is what creates very quickly immediate empathy with the character.

I don't know if this game is self-referential in any way, but I wanted to ask the question of our real degree of freedom in real life, how many options do we really have, in an interactive experience that is defined by choice and freedom.

There was a kind of interesting link between the story that is told and the vehicle of the story. I guess no one will care about these considerations, but I like the idea that it gives some depth to the game.

Telling stories is the most ancient human activity. Men started telling stories with paintings in grottos. Then they invented the language, wrote books, theatres, movies and television.

Every single new media that appeared was used for one thing: telling stories. Why would interactivity be any different?

The very first movies were very primitive: a train attack or a bank robbery. Then movie pioneers discovered that more interesting stories could be told and they invented their own narrative language.

We still have to invent our own language in games. This is the only way we can expand our audience and reach people who are not interested today in killing zombies in corridors. We all need to reconsider where we want this industry to go in the next ten years. Do we strongly believe that we can make first-person shooters forever or will we at some point lose interest and look for something new?

Fahrenheit brings my own answers. I don't know if all answers are the best ones, but I am quite sure that the game asks the right questions.

Whether an innovative game can be commercially viable is another question. If you consider ICO or Rez, you may answer "no", if you consider The Sims, you will answer "yes".

There is no doubt in my mind that interactive narrative experiences will be a significant part of the future of this industry, whether they follow Fahrenheit's path or define new ones. I cannot believe that we will limit this wonderful media to what it is today just with a better technology.

Interactivity has the potential to become a new art form very soon, following the path of cinema.

The main step we did was to define the experience as an emotional ride. When you think about movies or books, a major part of the pleasure you feel comes from the fact that you go through different types of emotions as you move along. You can feel sad, happy, jealous, in love, angry or tensed, the evolution of the emotions you feel during the experience defines your emotional ride. Most art forms could be defined in a similar way, by considering what you feel in front of a painting or a sculpture, for example.

When you consider an interactive experience as an emotional ride, it opens new possibilities.

In Fahrenheit, I also tried to rethink the way the interface works. Controls should not be the main challenge anymore, neither should it be a simple remote control to move your character. My approach was to see it as a possibility to create physical immersion, to make him feel what his character feels. The MPAR system we have chosen for actions is just one example of this approach that we push very far in the game.

I like to define Fahrenheit as an "interactive drama". Putting it in the adventure category may mislead people and make them expect a slow-paced experience, with a huge inventory where you need to combine objects and lots of 2D puzzles, which Fahrenheit is absolutely not. We could call it an "interactive movie", but then some people may remember these old games with real video where interactivity was very limited, and this is the opposite of Fahrenheit.

"Interactive drama" is really what defines the best what Fahrenheit is about.

Most publishers have their eyes turned backward rather than forward. They look at which games were successful last year and make the same game with a couple of new features the year after. Very few are able to have a real vision for the future.

Narrative-driven games were one of the most successful genres in the first age of video games. Text-based adventure games had a great success at the time.

But adventure is a genre that has almost not evolved over the years. It remained stuck by the mechanics limitations and the difficulty to tell a truly interactive story. The technology was not there but also the writing techniques were not mature. It slowly became a niche in the market, especially because the genre remained PC-based because of its point-and-click interface, which meant not being present on consoles.

Fahrenheit aims to renew the adventure genre, and to show that it is possible to play within a story in an experience that is really interactive and fast-paced. I really hope that it will convince more and more publishers that it is possible to make games that are different.

Some important people at Vivendi immediately got the pitch two years ago. They understood that Fahrenheit could open a path in a new direction and create its own genre. But less than a year after we signed with them, all the key people had left the company. We had no one to talk to and we suddenly felt a little bit lonely without any kind of support. It quickly became obvious that no one in the new American staff had any time to spend trying to understand this strange new idea. We went to them and told them that we strongly believed in the potential of this game and that we needed a publisher ready to fully support it. Several publishers wanted the game, and we signed with Atari in the next following weeks.

Most of the recent adventure games have been made in the US where there is a large adventure community.

I don't think there is anything special in France regarding adventure games and Quantic Dream does not intend to make only adventure games in the future. We will continue to explore different directions while continuing to raise high expectations for the quality of narrative in our games.

The collaboration with Atari has been extremely positive for the game. They gave us a lot of very useful feedback and helped us to improve the game with total respect for our work. We mainly improved the control system, make the interface more fluid and speed up the pacing. The first versions of the game were very slow-paced, we discovered that the game was much more efficient moving faster. We also initially had some issues with the camera system. Given the fact that we always have several cameras, we had some issues with character's navigation that you would not normally have with just a camera in the back of the character. We get great feedback from Atari and focus groups that helped us to fine-tune the game.

After having collaborated with David Bowie on my previous game "Nomad Soul", I was looking for a composer able to bring a unique style to the soundtrack. I was looking for something based on emotion and humanity, something subtle and atmospheric. As a big fan of David Lynch, I knew the work of Angelo since Twin Peaks until more recently his collaboration with Jean-Pierre Jeunet in "A Very Long Engagement". I really appreciated his unique ability to bring emotion to his soundtracks.

As far as I know, Fahrenheit is his first collaboration to an interactive experience. Angelo has written music for the best directors for a long time. He is an open book about movie history. It is fascinating to hear him talking about how he worked with Isabella Rossellini in Blue Velvet or how he did these incredible guitar notes in Twin Peaks. Listening to this old man telling you the back-stories of his work with David Lynch was really inspiring.

I guess Angelo was intrigued by what we were doing. He seemed to like the story and the ambiance, and didn't think about his work as if it was for a video game, but as if it was a real movie.

Working with him has been extremely easy. He took a lot of time to really understand what Fahrenheit was about. He wanted to know everything about the story and the characters. I really had the feeling that he translated the soul of Lucas into a musical theme.

I absolutely want to continue working with movie composers. I think they really bring something unique to games that we rarely find. The good movie composers have the power to express emotions through their music. They can help us to bring games to the next level.

Head here for part two of our interview with David Cage.