Harold Halibut review - sub-aquatic sci-fi adventure is a little too prog-rock

Space-mod at sea.

What if a game was intentionally quite boring? This feels like the premise with Harold Halibut, and at first it's kind of brilliant. You take on the role of the eponymous janitor here, a kind of lab-assistant-slash-gofer and general multipurpose dogsbody aboard the Fedora. A crashed colony spaceship that set off from Earth some time in the late 70s or early 80s, the Fedora has now been stuck, for about 60 years, deep beneath the ocean on a predominantly liquid planet, becoming a kind of self-contained commune that only partially longs for home.

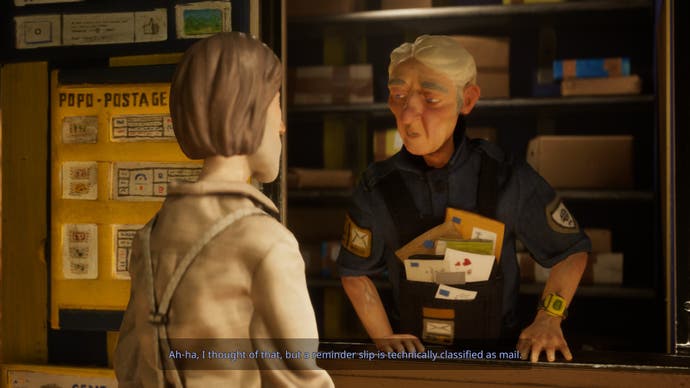

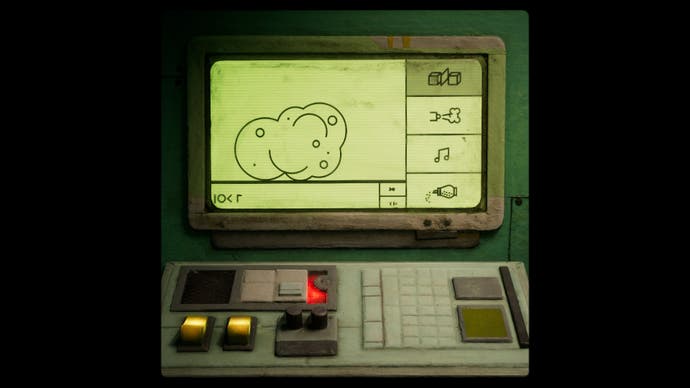

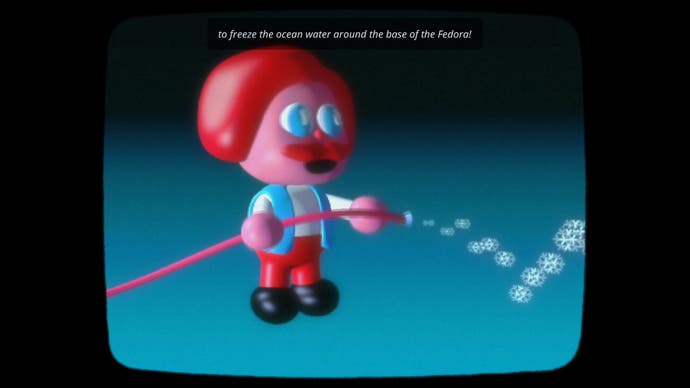

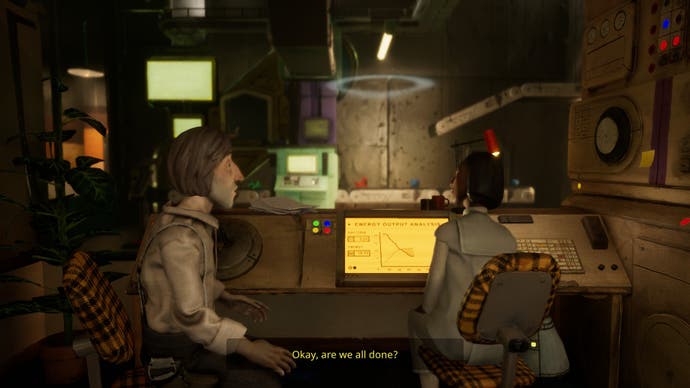

It's a wonderful setup, enabling debut developer Slow Bros to do some of its best work. The Fedora is an extraordinarily realised piece of human craft, with the game built of hand-made, intricately worn and weathered models and sets that have been digitised for animation. Combined with the choice of era you get this kind of Aardman-style visual effect and a deeply retro-Brit kind of humour, centred on bureaucratic Post Office procedures and varying forms of jobsworth. The ship itself, for instance - green-hued, sub-aquatic and slightly industrial, like a miniature village built inside a spirit level - has been subsumed by the unremarkable small-town corporation All Water, with little CRT tellies around the place intermittently buzzed with corporate infomercials and announcements.

During these - and similar opportunities for squiggly-lined, wobbly-audioed video feeds or moments of rickety old-school lab computing - Harold Halibut is probably at its best. Animations, decorations and nice little buttons, even in deeply rudimentary puzzles, are completely enchanting. The humour, when it lands, zeros in on a niche but ever-present part of the collective British psyche, the selfishly entrepreneurial mindset of a very specific kind of small-minded, curtain-twitching, 80s-era middle class. Unfortunately, those moments are quite rare, and the better parts of the rest of the game are weakened by how relentlessly, brutally, interminably slow things are to move forward.

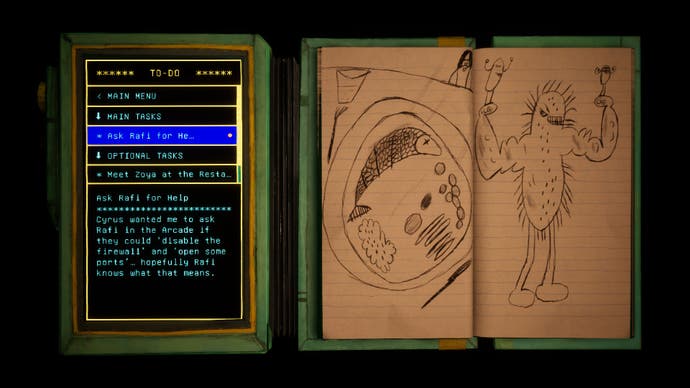

Take the early discovery that the Fedora is facing an energy crisis. Primed to be the perfect inciting incident, your first few tasks after this instead revert to the usual routine: trotting across to different regions of the ship, delivering messages from one professor to another, or maybe if you're lucky, carrying an object back and forth. These are punctuated by some meandering conversations with other Fedorans about their day-to-day issues, and a few optional side-tasks, then it's back to your little camp bed in the laboratory basement and on to another day.

At first these conversations are charming: you learn that Chris Tenenbaum, a buff but sensitive teacher, is obsessed with Turkish TV melodramas. A shop owner keeps making grand gestures to regain the love of his scientist wife, who's main issue is actually that she just needs a bit of space to do her work. A nice, elderly postman called Buddy likes going for his little jogs around the arcade district, a little row of shops and restaurants that exists, under the green alien sea, as a slice of life frozen in time and set to pleasantly sleepy elevator music.

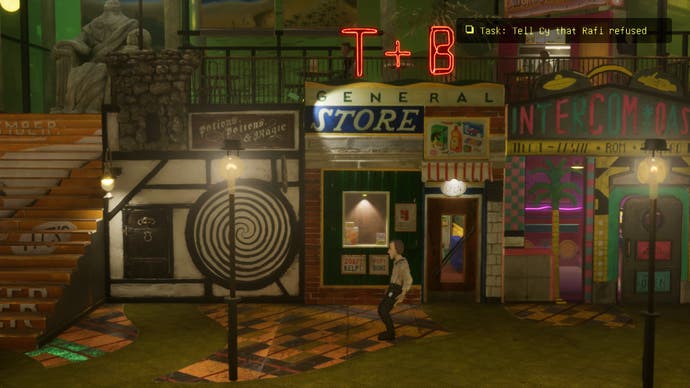

While that soporific pace provides room for some genuinely touching moments - in particular a later quest involving Buddy and some undelivered letters - it's also very much part of Harold Halibut's biggest problem. Slowly, as you flush your way between 'tube' connections from one district to another, back and forth and back again, you'll discover some minor tensions between the Fedora's citizens. But despite the urgency of your mission to restore power and escape back to Earth, despite Harold's crushing and at times poignant longing for more, the change in tempo never comes.

Instead: more discoveries, more seeds of mystery sewn or more narrative threads to untangle, which delay the story's conclusion but don't really enhance it (there's a lot of excess plot here, which takes far too much time to resolve, at about a dozen hours or so, for what is effectively as complex a situation as Chicken Run) and more languid trotting back and forth through the same handful of environments.

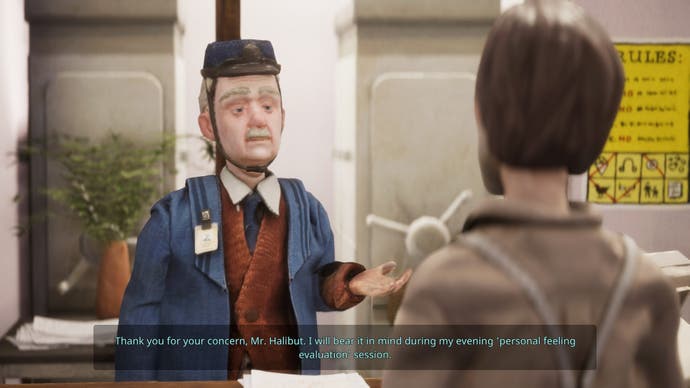

Fetch-quest after fetch-quest, gradually you will be worn down. On one occasion I was sent to deliver a message to someone - bear in mind everyone can just text each other down here, by the way - which was effectively: "Hello, can I help with anything?" only to get there and have that person tell me they didn't need any help, or want to chat. And then, on returning to the message-giver, I was told by them that it didn't even matter anyway. Even this wasn't on one occasion, but in fact several. (One character in particular had a reputation for never being willing to help and yet, several times, I'm sent to go and ask politely anyway and be rejected and, surprise, it didn't matter because something else came up that solved the problem).

Each little journey takes a couple of minutes: out from the lab, along the corridor to the tube, through the tube to a station, making a change there to get a different tube line to the destination, along another corridor, through another long, meandering conversation, and then all the way back. This happens so often, and your time is so aggressively and unceremoniously wasted, the impression is that this must be intentional, a means of putting you into Harold's miserable shoes and imparting some of his existential crisis onto the player. But even taken as an intentional device it just doesn't land.

Partially this is down to the characters themselves, many of which are colleagues and friends but are also almost unanimously patronising, disinterested or even cruel. I suspect this isn't intentional. It's certainly a deliberate theme that Harold is frequently overlooked and underused, but the writing here is muddled. Harold is mopey, talentless, and kind of dim, often chiming into conversations with an idea everyone's already thought of and dismissed. At the same time, other characters' lines are constructed in a way where they could be delivered as harmless, but are often read with a kind of accidentally withering cruelty. Almost every single person on the Fedora, even the sympathetic characters on paper, comes across as an almighty jerk, falling victim to that old video game dialogue problem of different voice actors clearly recording their halves of the conversation in insolation, and thus failing to get anywhere near each other's tone.

This also, like much of Harold Halibut's story, simply fails to progress at all over the course of the game. Right up to the final act I still found myself being berated as a "nincompoop" and blamed for things entirely out of my control, as Harold continued to huff and puff, even post-third-act-revelatory experience, at being nothing but a spare part. Coupled with a good number of jokes that don't come close to landing, and some truly interminable conversations about nothing much at all, and the writing becomes a fairly major drag. There's an intermittent bug in Harold Halibut that accidentally advances an entire conversation instead of just the current line when you skip ahead, making everyone in the room speak at once - but there were times where I was genuinely glad it came up. Skim-reading the dialogue as it flew by, it's rare that anything significant was missed.

Ultimately, the effect is one of gradual erosion, with repetition grinding away at the impact of certain scenes, or conversations, or even little elements of visual detail. I love the Fedora's floorboards, its mechanical quirks, its hand-drawn posters on the walls and wonderfully angular, mid-century utopia of a Social District, but I love them much less on passing each by for the hundredth time. The same goes for the little London Underground-style tannoy announcements on embarking and disembarking from the tube: cute at first, I love them much less when I have to make several back-and-forth tube journeys in the space of a couple minutes.

Even the game's big, climactic visual moments go on for too long. An encounter with an alien species (not a spoiler, don't worry) and a trip to their special cave, set up with strange musical installations and food vendors like a particularly hippie exhibition at the Southbank, take too long, lack much purpose, and fail to offer too much to the conversation beyond a faintly philosophical shrug. That, and a few late-game sequences are shooting for somewhere around Beatles-meets-Pink Floyd, but falls into the trap a lot of would-be enlightening prog rock can do in, once again, lingering on the point for far too long.

It makes for a huge shame, and also something of a waste. Parts of Harold Halibut are utterly striking, and the world itself is a genuine achievement of tactile, human craft. Its story asks the right questions - big ones, about why we're here, who we meet, and what we're supposed to do with it all. And the idea, at least in theory, is somewhat genius. A genuine anti-hero, Harold Halibut is effectively a passenger on a story acted out by the actual experts.

What happens when a story not only doesn't make you the chosen one, but also doesn't give you any kind of favourable treatment at all? Where you're not at all qualified, just in the right place and the right time, and the real experts don't automatically use that as an excuse to drag you along with them and make you the de facto protagonist from then on? What happens if fetch-quests are your job and you lust for something more, but actually, fetching things is all you're really able to do? What if, in attempting to directly put a player into those shoes, you intentionally patronise them, waste a couple of hours of their time, and make them really quite bored?

I'm deadly serious when I say that's kind of brilliant. If it truly is the intention, as I think it is, then I'm delighted to have played a game that tried it - as Harold Halibut's bosses often exclaim, these kinds of scientific experiments can be great fun, regardless of the results. In this case some better execution would definitely have helped, but despite moments of real beauty, invention and craft, some genuinely heartfelt philosophising and sincere warmth, the premise of this one was probably just a little flawed from the off.

A copy of Harold Halibut was provided for review by Slow Bros.