Happy Go Luckey: Meet the 20-year-old creator of Oculus Rift

"This was my thing. This is what I did."

"I'm a self-taught engineer, a hacker, a maker, an electronics enthusiast. I'm from Long Beach, California. I like making things. My dad was a car salesman, my mum was a stay-at-home mum. I was home-schooled for a long time. I started taking community college courses when I was 14 or 15. In 2010 I started going to [California State University] and I was a journalism major.

"I'm a pretty regular Joe."

Today he's worth millions of dollars, this regular Joe. He is Palmer Luckey, the 20-year-old inventor of Oculus Rift, an affordable virtual reality headset that's taking over the world.

***

Palmer Luckey's no gibbering genius, no stereotypically geeky inventor or recluse. He's no aloof mind honed at prestigious institutions, either. He's polite, upbeat and comfortable in conversation - he's even handsome in a rosy-cheeked way. Confront him on a topic that isn't head-mounted displays or virtual reality and he is that regular Joe he believes himself to be.

Broach his mastermind subject, however, and his passion is revealed. While friends and fellow students filled their spare time with social activities, Palmer Luckey was in his parents' garage, collecting and modifying head-mounted displays. "This was my thing," he says on the phone with me. "This is what I did."

The seed was sown not all that many years ago by the pages of science fiction novels showcasing impossible technology, gadgets and gizmos. The internet then provided the infinitesimal how-tos he would need for his tinkering to progress.

The path to Oculus Rift inadvertently began in 2009 when Luckey was only 16. "My goal actually wasn't to make something," he explains. "It was actually just to buy something - I assumed there must be something out there that was really good that I could use for gaming."

He made money by buying, fixing and selling mobile phones, doing odd jobs for people and working at a sailing centre, scrubbing boats and cleaning the yards. He used that money at auction acquiring rare head-mounted displays - expensive relics - at a fraction of their original price.

"My biggest score was a unit that originally cost about $97,000 in the 90s," he tells me, "and I picked it up for $80. Shipping wasn't included and I had to actually drive to the warehouse and go get it, but those are the kind of deals you can get... There's very little demand for outdated virtual reality equipment."

Luckey soon began to realise he wasn't going to find, ready made, what he was looking for - even the high-end professional equipment didn't measure up. That's when he decided to take matters into his own hands.

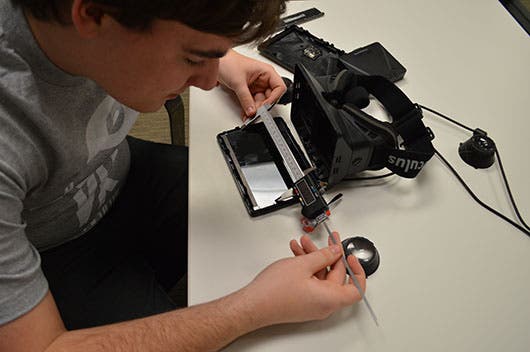

"I started to collect them and bought a lot of them from government auctions and industry equipment liquidation sites and all kind of fun places. I took them apart, looked at how they worked, tried to learn what do they do right, what do they do wrong and I started to try and modify some of them and make them into something I would actually want to use," he says.

"And over time it became clear that the only way to make something that was really good would be to throw out the design book that everyone else had used and start from scratch."

It took years to get to the point of deciding he'd have to make something himself - that and dozens of auctions. Today he has 56 unique head-mounted displays, not including any he's made himself. "I believe it's the largest private collection in the world."

***

The road Palmer Luckey was on led directly to Oculus Rift, although the then 18-year-old still had no idea nor expectation of the extraordinary success that await him. "I wasn't actually aiming all that big," he confides. All he wanted to do was share his VR headset with what he describes as the "vanishingly small" enthusiast VR community of the time.

"My plan was to do a Kickstarter for about 100 of these things - basically, to get money to buy all of the components required on a slightly larger scale and then send these out to people as kits so they could assemble them themselves using my instructions so they could have the same thing as I had. I figured it would be a really cool thing to have a couple of VR nerds toying around with."

His modest ambitions would be turned on their head, however, when one of those interested "VR nerds" turned out to be none other than legendary id Software programmer John Carmack.

"He started posting [on the VR forum] because of his own virtual reality project. In fact, when we originally started talking, before we talked about my stuff, Carmack and I were talking a little bit about modifying one of the other head-mounted displays he had and why it would be extremely difficult to do so," Luckey recalls.

"But he ended up seeing my head-mounted display work and asked me, 'Hey, what you have looks interesting - is there any chance I could buy one?' He's John Carmack," Luckey snorts, "I just gave him one instead - you can't turn him down."

What Carmack did next was announce Oculus Rift to the world by demoing Doom 3 BFG Edition on the prototype device at E3 2012. "He just went off and did it on his own because it was fun for him," says Luckey. Our Oli Welsh was one of the journalists invited to try John Carmack's wacky VR goggles at the time, and he was captivated by the potential.

"That's really when it started to get a lot of attention," says Luckey, "and it went from being maybe 40 or 50 people who were interested in the Kickstarter to - you know, [Carmack] mentioned 'oh he's going to make a Kickstarter for these', and all of a sudden there were thousands of people who were very interested."

That's when Palmer Luckey dropped out of college and decided to pursue his passion full time.

***

He started the company, Oculus VR, at around the same time because he needed one to be able to run a Kickstarter campaign. It was still only him, and still his expectations of success were low. His original Kickstarter pitch, he tells me, was pinned on a different video "much inferior" to the one up there now, but the world would never see it because those ripples Carmack had created at E3 had stirred more than just curious journalists.

Seasoned tech professionals Brendan Iribe and Mike Antonov, from Gaikai and Scaleform, were interested. One meeting led to another and soon they were on board, Iribe as CEO and Antonov as chief software architect. "They helped make it into something that was much bigger than a few kits," Luckey says. A proper company had been born.

Iribe and Antonov encouraged Luckey to take Oculus Rift on the road and show it to some big names in the hope of endorsement. Luckey had a relationship with Valve that stretched back to before that milestone E3 - "they were also planning on buying a few of my prototypes, just a few early ones" - so he started there.

"We went up there with a Rift and we showed it to all of them, and everyone there was pretty impressed with it - they thought it was a really great virtual reality headset for the price. And so we were lucky enough that they were willing to appear in our Kickstarter video."

It isn't just anyone in the video, though - it's Gabe Newell and hardware guru Michael Abrash. That's one heck of an endorsement. "It is pretty massive," acknowledges Luckey, "and there are several people like that in our video. It's funny because really the reason that they're endorsing it, it's not necessarily that they're just endorsing me or saying my thing is great, it's really a testament that the technology is finally ready. "

Modesty, always modesty.

Endorsements bagged, the Kickstarter campaign was ready. Luckey's feet had barely touched the ground. "It was very exciting, it was very cool that VR looked like it was going to get more attention than it had been. I had been saying that VR was going to be big for a few years at this point, but it wasn't until now that I realised that people were actually reasonably convinced that it was possible."

The gates opened and the money started flooding in. Oculus Rift was funded in a day, although Luckey was too busy at QuakeCon demoing Rift to give it much thought. "I couldn't really let it distract me," he says, "but it was pretty incredible." Yet as the campaign ran on, the numbers kept rising, and he finally began to sense the scope of what he'd begun. "I started to realise that it wasn't just going to be a successful Kickstarter - it was going to be one of the more successful Kickstarters out there."

The Kickstarter campaign ended on 1st September and Palmer Luckey's Oculus Rift had raised 974 per cent more than it set out to. Nearly 10,000 believed, and they'd raised $2,437,429.

***

"You'd actually be surprised - I don't think my life actually changed all that much," he tells me. "The operations changed a lot, the scale did, a lot of new people came on board, we got an office - a lot of things like that. But really I was continuing to do the exact same things that I had been doing before."

He tinkered, modified and invented while the experts he'd hired did what he didn't know how to - develop the all-important Oculus Rift software developer kit. Building the hardware is easy, he tells me (although I suspect that for normal people it really isn't), it's putting the tools in developer's hands so they can easily use it that's not.

A year, many hires and a hardware delay later, there are now 17,000 Oculus Rifts out in the wild. What's so special about that number is that it's in the hands of indie developers we're seeing the most fruits. It means Rift is not only affordable, it's also easy to work with. Developers talk freely about supporting Oculus Rift and when they do, the queues are long and the intrigue high; at the Rezzed UK game show this year the question everyone asked was if you'd tried Rift.

Indies can more easily base concepts on Rift and work them up quicker but the VR revolution is by no means restricted to them. Just this week, a picture tweeted by a Konami producer suggested Oculus Rift support for Castlevania: Lords of Shadow 2, and it's a happy extrapolation to wonder one day what it would be like to explore a sumptuous Elder Scrolls fantasy world in true first-person perspective.

The groundswell of momentum around Oculus Rift crescendoed recently when Palmer Luckey announced his company had raised $16 million in private funding - a sum that eclipses anything Kickstarter can achieve. That money will fully realise Luckey's dream: putting Oculus Rift on shop shelves for people like his 16-year-old self to buy for gaming.

That consumer version of Oculus Rift will be better than the dev kits are now. Features aren't set in stone but Luckey knows he wants it to be higher resolution, have positional tracking, lower latency and be within the same $300 price range as the dev kit is now. Whether $16 million can fund all that, Luckey doesn't really know. "We have no idea!" he jokes in the way a young and successful person can.

There's a broad plan to improve the hardware incrementally after it comes out, but whether that's a yearly cycle depends on the pace of technology improvements and, of course, how well the consumer Rift does. It doesn't sound like there's much of a plan beyond that, and if there is, he's not sharing it. The only other thing in development at Oculus VR besides the consumer Rift is a latency testing device.

***

I ask him if he's a millionaire now and he laughs. "I mean I'm a millionaire in hypothetical dollars..." he trails off. "No I don't have a ton of money; I have equity in the company. But we're not planning on selling the company or doing anything to liquidate that - we're trying to remain independent and build what we're building."

In the space of four short years, Palmer Luckey has gone from being a regular Joe in his parents' garage, tinkering with head-mounted displays, to being the head of a 30-person team and the face of virtual reality in gaming. Unsurprisingly he says it's all been a bit of a blur. "Most of the things I would point out as being really exciting or standing out to me are things that wouldn't sound very exciting or standing out to normal people."

I try him and he's right: figuring out aspheric optics is a highlight that doesn't capture my journalistic imagination. There is a tragedy that sticks out like a sore thumb - the sudden death of Oculus VR co-founder Andrew Scott Reisse - but Palmer Luckey isn't ready to talk to me about it. "There's no Facebook-style story," he adds. "No tales of parties and crazy stuff going on that was really a highlight. It was just kind of a slow plod towards making this thing a reality."

But what a reality he's created; he's brought science fiction to life in a gaming world that was looking all too understandable, all too sensible. In not revelling, this unassuming self-taught engineer, hacker, maker and electronics enthusiast has produced a thing that will capture more than just my imagination, and will do for many years to come.