Flock review - the art of noticing

Baa none.

Down in central Brighton, where the city meets the sea, and resting under the latticed shadow of a burned-out hotel, there's a traffic crossing where someone has stuck a set of plastic googly eyes on one of the green men. I don't know how long these things last, but if you're around in the next few days you can probably still see it. I noticed it because I was out with my daughter and she always notices these things: a green man who stared back at us while we waited to cross the road with the rest of the human throng.

Noticing things is having a bit of a moment just now. Have you noticed this? There are best-selling books telling you how to pay attention more effectively. On TikTok you'll scroll and stop on videos of rainfall on city streets, seabeds stained with the ripple of surface water overhead, fleeting shapes forming and unforming in the sun-rimmed clouds. Tagline: the art of noticing. Here you'll find beauty and riches, here are gifts that are only available if you've first taught yourself to see them.

And then there's Flock, and Flock feels very much of a piece with this sort of thing. It's a game about wildlife and it's a game about collecting stuff. But it's also, serving as bedrock for all of that other stuff, a game about noticing. Its world is there to reveal itself to you, but only when you're ready. Only when you're in sync, only when you're properly attuned.

A bit of taxonomy up front. Well, a bit of lineage anyway. Flock is the latest game from Hollow Ponds and Richard Hogg. This is the team that made the almost indescribable snake-controlling game Hohokum - "snake-controlling game" is a truly terrible description for a game as roving, restless, and experimental as this - and there's a little of Hohokum's sinuous, propulsive movement here as you send yourself skimming through the skies and across the grass. This is the team that also made I Am Dead, an ensemble-based exploration of mortality inspired by a video of a banana in an MRI. In I Am Dead you discover the world and its story through its bits and pieces. You rustle through it all like it's just one big junk shop. There's something of this to Flock too.

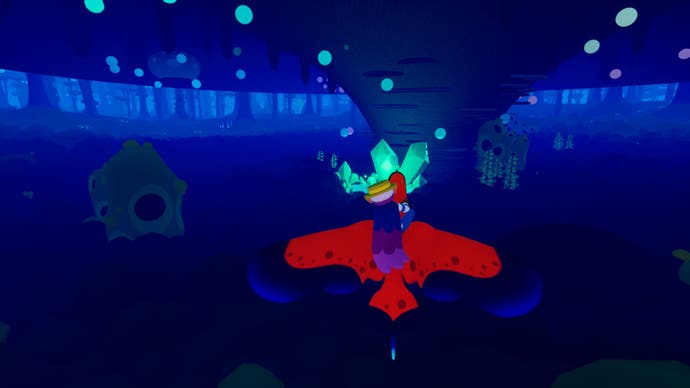

More than anything, though, Flock is just Flock - and that's more than enough. You set out from a hilltop to explore a landscape of grass and rock and moss and concrete and wetlands. You're riding on the back of a chummy red bird, and you're hunting for examples of local wildlife. As you find more of these examples, the world expands and yet more of these creatures become available. How do you hunt them? Actually, hunting is exactly the wrong way of looking at this. You spot them. You learn to see them. You teach yourself to notice them.

And this works in various ways. On arrival in a new area, a handful of creatures will just be gadding about, flying through the sky, basking on concrete, snuffling through the grass. Everything in Flock is soft-edged and gently comical - everything is at home in a world of green men wearing googly eyes - so these flying, basking, snuffling things will have candied rainbow stripes, derby cane Gonzo noses, brisk little wings holding them aloft. Spot more and they start to arrange themselves into families: Gleebs, Winnows, my beloved Thrips. But not all of them will be so easy to find.

Some will only be available at certain times of day, and day scrolls gorgeously through the sky here, delivered in seventies snapshot blooms of pink and purple and golden light, while night stains everything a rich blue as a huge pearly moon sits in the sky. Those Thrips, which light up as they buzz around, will often only appear around trees when it gets dark. Other creatures will require the morning before they make their rounds. Others still will only bask at noon.

But the time of day is still only part of it. Other creatures need certain environments - trees, long grass, but also wetlands, a certain lucky hill. Some will hide in clumps of fallen leaves. Others will disguise themselves as rocks. Some will have specific calls to listen for.

So from this simple point there are already two ways of looking in Flock. In one of them you ride around on the bird and you look for creatures out in the open. But in the second you switch to a first-person focus mode, or you settle on a perch and zoom in on the details. This is how you seek the stuff that really doesn't want to be found, that has discovered ingenious, sometimes convoluted means of hiding itself.

There are aids on this quest of yours. You are gathering a list of every creature you spot, arranged into neat families, and each missing niche on the list will have a little clue that points you in its vague direction. Some creatures might like a certain part of the expanding biome. Some might require you to track down a male species first. Some have pretty much full-blown recipes for uncovering them and some have just the slyest, the skinniest of Cryptic Crossword clues. It's enough, though. These prompts, combined with an environment that just calls out to you to be explored, is enough to see you through.

This all works, and feels so singular, for a handful of reasons. The first is that movement is so lovely. Flock handles your height for you, so you just pick a direction and a speed and set off. The world slips past you, around you, while certain features of the landscape will shunt you high into the sky. You're moving forward but never only forward. There's a subtle sense of curving to your momentum, as if you're a stylus in the groove of a spinning record. It's lovely to set off and see where you end up, threading through forests, picking over moss, rushing up against the Fauvist trees and the soft, even-tempered Ravilious hills and hollows, encountering strange, sculpted lumps of old broken concrete that hint at an artful past that can never be recovered.

And then there's the creature design, which is goofy and magical by turn. Here are treble clefs and air quotes and carpet runners rippling through the hidden thermals of the air. They're ridiculous flights of fancy, to which I say: have you seen actual birds recently? The bumbling admiral on patrol that is the overfed seagull, the watercolor ghost we call the Jay, trimmed in rust and seaside blue and with a dot matrix printer for a voice? Flocks' bestiary feels like doodling, but it also feels like it's born of studying nature, really looking at it, seeing the wild invention that keeps it all moving.

(And this is Flock, remember, so you don't just spot these creatures. Over time, and with the correct whistles discovered, you can collect them too, charming them with a simple mini-game and adding them to the ever-growing crowd of animals that just follows you around. It's lovely stuff.)

And finally, Flock works so well because of a secret ingredient that goes hand-in-hand with noticing, that lights it all up from within.

This ingredient? When the writer Helen Macdonald was young and out bird-spotting with their dad, and they were restless and perhaps a little frustrated at all the waiting around, something brilliant happened.

"And then my dad looked at me," they write in H is for Hawk, "half exasperated, half amused, and [he] explained something. He explained patience. He said it was the most important thing of all to remember, this: that when you wanted to see something very badly, sometimes you had to stay still, stay in the same place, remember how much you wanted to see it, and be patient."

Flock does this. And it does this with great daring. Time is compressed in a video game: a little time passing can exert a great toll. Flock absolutely knows this, and yet it will still push you to be still and wait and watch - and it will extend this waiting and watching much more than you might initially anticipate. And so the other day I spent literally fifteen minutes under a pink-leafed tree, waiting for something I just knew was going to emerge, and when it did I actually yelped with happiness. I spent a whole night in the wetlands - a human, non-Flock night - looking at promising rocks and not seeing much else. Looking back, I wasn't frustrated. It wasn't like when I was a kid and I'd lost a tiny piece of Lego and had to walk back and forth, ploughing the carpet with my eyes as a hot pain settled into my brain. It was lovely to wait in Flock. It was lovely to patient. I was paying attention. I was ready for bright things to happen. I was right where I was meant to be.

This is my Flock, anyway, and maybe yours will be different. There's a whole quest-line about tracking down stolen items, which involves dispatching sheep to eat the grass on certain hills. There's that creature charming component, and that alone for some players will become transfixing. And then there's the fact that Flock is made to be played online with friends, friends swooping and gliding over the rounded earth, noticing things together.

But for me it's a solo affair. Give me the moonlight, give me my beloved Thrips to gad about overhead. Give me that moment where I've studied the creature catalogue and the map and the landscape so intently that when a sausagey, trumpet-nosed creature appears in the distance and I realise I've never seen it before, I instantly think: Bewls. That's a Bewl. A new one. I've waited for it, and now it's actually here.

Review code for Flock was provided by Annapurna Interactive.