Fe review - uneven indie from EA Originals

Noisy, cutish and short.

"If only we could talk to the monsters," laments an infamous Edge review from many moons ago. In Fe you don't just get to talk to the monsters - you get to sing to them, or at least, croak and wail tunefully, like a sheepdog trying to nail the backing vocals to Bohemian Rhapsody. An "EA Original" from Swedish developer Zoink - otherwise known for such comicbook fare as Zombie Vikings: Stab-a-thon - Fe is the story of a nimble fox creature on a mission to save a vivid dreamland from a legion of strange armoured figures, who are capturing and processing the wildlife to unknown end.

It's a game about healing rifts between lifeforms, about symbiosis and diversity versus entrapment and exploitation, and integral to all that is the singing mechanic. As in a Metroidvania, you'll need to obtain certain abilities to push deeper into Fe's persistent, multiple-region map, which extends from glowering lava caves and sherbet yellow swamps to chilly blue mountain-tops. Some of these abilities are bog-standard incremental power-ups, acquired by collecting purple crystals, but the majority take the form of animal calls and chants, used to woo the realm's critters and flora into doing your bidding.

If you know a creature's language, you can hold right trigger to sing with it, increasing or reducing pressure to change pitch. Harmonise with the other animal for a few seconds - as indicated by a glowing waveform between mouths, which creates the unnerving impression that you're tongue-wrestling it into submission - and it will consent to follow you around and help you overcome any obstacles nearby. Birds will illuminate the route to your current objective, their wingtips scribbling golden paths in the air like the scoutflies of Monster Hunter World. Boars will clear away clogs of blue fungus, or carry you up slippery hills of ice. Stags will flatten any hostiles you lure into their territory.

You can sing to plants, too, activating them as bounce pads, seed dispensers and the like after you've mastered the local dialect. There's no direct confrontation or combat as such in Fe, no means of dealing with threats save diving into spiky black bushes and waiting for the AI to lose interest. Rather, you are the unifying agent by which an ecology learns to purge itself, gathering together each species' traits and pitting their combined variety against the invader.

It's a lovely setup on paper, steeped in a fondness for a familiar selection of wistful landscape games and tales of ruin and renewal. There are the obvious fingerprints of Journey, with its wordless incantatory shouts and graven images of apocalypse: probe the crevices of each area, and you'll find painted monoliths that shed a little light on the world's origins. There's something, too, of the melancholy grandeur and karmic feedback loop of Shadow of the Colossus. One region pays explicit homage in the shape of a giant, wandering stag that must be scaled, limb by limb, though thankfully not stabbed to death.

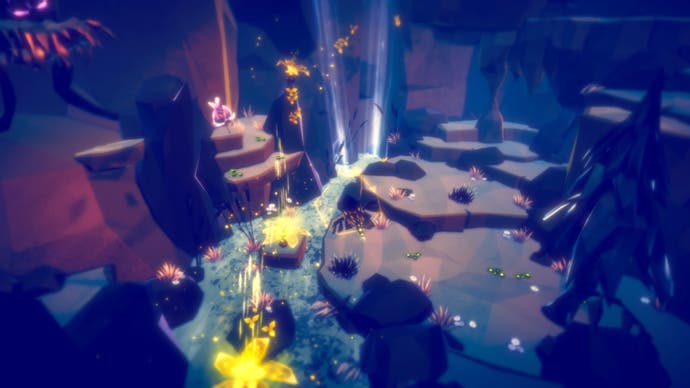

Sadly, Fe often seems more interested in capturing those influences and a certain glossy, self-serious flavour of "indie" gaming than delivering on its concept. As with the first EA Original, 2015's sweet but skin-deep Unravel, there's the strong sense that this is a reputation-building project for the publisher, an attempt to curry favour with those who see EA as one giant AAA microtransaction machine. This comes across especially in the orchestral score, which is often nicely sequenced to your progress through an area, but also syrupy and unsubtle, like it's trying to brute-force your limbic system with shimmering violin crescendos. The art direction, too, leaves a muddled taste. There were times when I was captivated by Fe's stylised Nordic aesthetic, with its tumbled stone silhouettes, crystalline blossoms and liquid play of light levels and filters. There were also times, perhaps more often than not, when I found it suffocating and abrasive.

For a game about harmony Fe also doesn't hang together that elegantly. The platforming hits its marks for the most part but can be fidgety and dissatisfying, particularly once you acquire the ability to glide. You'll often find yourself bumping against ledges, straining to initiate the mantling animation, or fighting the camera after overshooting a platform. In a welcome concession, the game lets you hop quickly from handhold to handhold when climbing trees by tapping the jump button, but this also makes it easy to accidentally leap from the top. There isn't that balance of readable animations and inertia you associate with the best platform games, which creates a low-frequency undertone of frustration.

The game's puzzles are even less convincing. As promising as the idea of bonding with other animals may sound, Fe's birds and beasts soon reveal themselves for a procession of robotic props within some rudimentary, lock-and-key level design. Beyond squealing at the wildlife till it caves in and opens the way ahead, most puzzle solutions boil down to hoiking seeds at smashable objects or chaining together jumps and glides while avoiding the eyes of prowling sentinels. It all feels quite piecemeal and brittle, though things do start to come together in the third of Fe's paltry three hours. The final area is a multiple-tier conundrum in which you navigate the innards of a moving structure, using all of the languages you've learned in tandem, and the revelation that follows is genuinely rather poignant.

Fe's real masterstroke, however, occurs after the credits, when you're left to wander a landscape freed of both the cloying soundtrack and hostile presences - scooping up the last collectibles, drinking in the vistas and witnessing the effects of your triumph. Fair enough, it's just a freeplay option, but it speaks powerfully to the theme of restoration and coexistence: after all, in most games the world is cast aside the very instant it's saved. Moments like these point to the experience Fe could have been if it were less ramshackle, less enthralled by certain arthouse titans and more committed to its own promise. Alas, the experience we're left with is mesmerising but a bit of a cacophony.