Xbox Series X silicon: the Hot Chips 2020 breakdown

How Microsoft architected its next generation processor.

Earlier this week, Microsoft took part in the Hot Chips 2020 symposium to deliver its now traditional console silicon breakdown, this time focusing on the core make-up of the Xbox Series X 'Project Scarlett' processor and how it compares to its predecessors. Not only did we learn more about the properties of the chip, we also gained an insight into the market conditions surrounding and influencing its design. The conclusion is inescapable: cutting-edge consumer electronics can still deliver generational gains in performance - Moore's Law isn't dead - but costs are rising and these are having a fundamental influence on the way Microsoft shaped its new console.

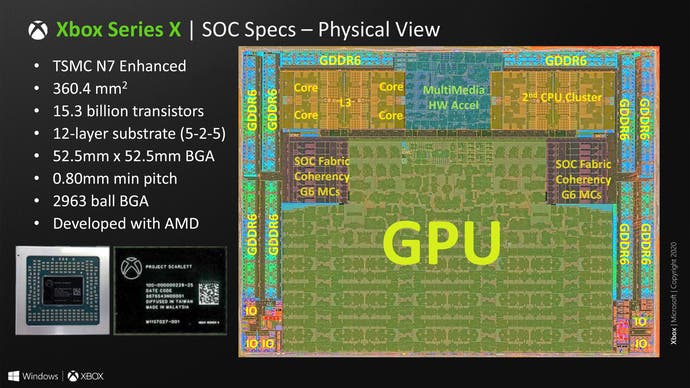

Kicking off the presentation, Microsoft's silicon engineers revealed the Xbox Series X processor lay-out - the die-shot - showing how all of the individual components slot into place within a single 360.4mm2 slice of silicon. Showing how much space the CPU, GPU and other key components are allocated gives us some idea of their importance to the overall design, and the balance looks similar to what we've seen in existing AMD-based consoles. Around 47 per cent of the entire area is gifted to the 56 AMD RDNA 2 graphics compute units (four of which are disabled in order to allow chips with minor defects to make their way into production consoles) with around 11 per cent of the space given over to what Microsoft describes as server-class Zen 2-based CPU clusters. A similar amount of area is also consumed by the GDDR6 memory controllers - there are ten of these in total - and while they address 16GB of total RAM in a retail console, the channels are also good for 40GB of memory in the Project Scarlett devkit, and we should assume that once integrated into the Azure cloud, the chips will be using some other kind of non-retail memory set-up.

Referring to the CPU clusters as server-class has caused some confusion as the basic configuration and cache set-up is remarkably close to AMD's Renoir design (Microsoft has a 'Hercules' codename internally for the CPU design) used in its Ryzen 4000 notebook line, as opposed to the monstrous many-core Epyc offerings that are actually used in enterprise environments. It's far more likely here that server-class designation simply refers to the necessary security features and memory support required to integrate the Scarlett silicon into the Azure cloud. The importance of the processor's cloud support can't be understated: the chip can run and stream next-gen games, obviously, but it can also virtualise four Xbox One S instances simultaneously.

We can also assume that these server-class CPUs will also take their place as standard Windows servers when not used for gaming - and if that level of validation for the chip has been achieved, there are some intriguing possibilities in deploying the chip for the Surface business. A new Surface Studio all-in-one with an Xbox mode would be a unique and eye-catching product, as an example. With an Xbox Series S now all but confirmed via a controller/packaging leak, a smaller, more power-efficient SoC could also work nicely in a laptop or small form-factor PC. Put simply, there are possibilities here.

Core to the whole Hot Chips presentation is the way that costs in the semi-conductor industry are looking somewhat challenging, requiring innovation in processor design. The outlook is bleak in some respects, but optimistic in others. The good news is that according to Microsoft, Moore's Law is not dead. Transistor density is still improving and comparing Series X with the vintage 2013 Xbox One silicon throws up some remarkable comparisons. First of all, in terms of physical size, the Series X processor is actually smaller than Xbox One's: 360.4mm2 vs 375mm2. Transistor count in just seven years has ballooned from 4.8 billion to 15.4 billion - a 3.2x multiplier. GPU compute power has risen from 1.3 teraflops to 12.2, a 9.3x improvement. Even the comparisons up against 2017's Xbox One X look good - a 2.3x multiplier on transistors and a 2x boost to compute.

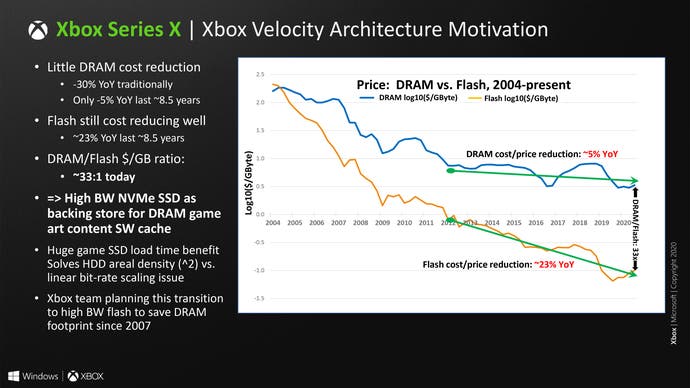

Scalability is there, but the landscape has changed. Xbox One X's 16nmFF processor was smaller than the original Xbox One's but more expensive to produce, and the cost has increased still further in the transition to the new, enhanced 7nm process. In the past, cost per transistor was lower - now, the opposite is true. Meanwhile, there are other pressures to contend with. A 30 per cent year-on-year reduction in the cost of memory has dwindled to a mere five per cent, meaning that not only is the silicon more expensive, improvements to memory capacity in line with the 8x boost from Xbox 360 to Xbox One are no longer possible. There's not much Microsoft can do to combat the cost per transistor conundrum - though dedicated hardware for elements like variable rate shading and ray tracing certainly helps - but necessity is the mother of invention, and that's why Microsoft developed shader feedback sampling.

The basic idea is fairly simple: texture maps are stored at different quality - or mip - levels. The size of texture data is ballooning already as we transition into the 4K resolution era, so the idea is simply to stream in the portions of texture data that are actually required, delivering what Microsoft says is anything up to a 2.5x multiplier to memory. It's part of Microsoft's Velocity Architecture, which seeks to maximise Microsoft's investment in solid state storage. There, at least, the economics look more positive. While there is an initial hit in transitioning from hard drive to SSD, the year-on-year cost reduction with flash NAND looks positive - Microsoft says it's in the order of 23 per cent. While it's potentially a way to cut prices over time, it may well be the case that it'll open the door to higher capacity console SKUs that don't cost the earth.

The Xbox Velocity Architecture also opens the door to new features like Quick Resume, which I do think deserves a little more focus. During our visit to Microsoft in March, we got to see the Series X console swapping between game states from a number of Xbox One X titles running under backwards compatibility. The amount of system memory allocated to Xbox One X games is 9GB, and it takes around 6.5 seconds to swap between them - meaning that the process of saving off 9GB and streaming in a previously cached state is astonishingly quick, especially when the processing of writing the data will likely be taking more of that 6.5 seconds than reading. I'm very optimistic about what solid state storage can do for the console experience, but I do think that it may take time for developers to transition their engines across to make the most of it. Perceptibly 'instant' loading may be possible, but whether we'll actually see much of it in the short term remains to be seen - and I think that will apply to both of the next-gen machines based on some the discussions I've had with third-party developers.

Returning to the Hot Chips talk, we do learn more about the GPU, mostly from a block diagram of the arrangement of the shader cores. Those expecting a revelatory change for RDNA 2 from the basic setup seen in AMD's RX 5700 series may be disappointed - the basic arrangement and cache allocation looks to be a match, with the only noticeable change coming from the addition of ray tracing blocks. There has been some confusion here with gigaray metrics that vastly exceeds Nvidia's for the RTX 2080 Ti - but these are calculated in very different ways and are not comparable. We've seen Minecraft DXR running on Series X and it's operating at 1080p between 30 to 60 frames per second - very much in the ballpark of Nvidia's current generation RTX offerings. I'm more impressed that a fully path-traced RT experience was possible on Series X with just a month of development work (albeit with the existing Minecraft RTX codebase as a foundation) and with Xbox intrinsics support for 'to the metal' access, I'm really looking forwards to seeing what developers come up with.

The same goes for 3D audio, which has made me think a lot about marketing and presentation. Sony made a remarkable pitch for a revolution in 3D audio with PlayStation 5 with its Tempest Engine, talking about hundreds of audio sources accurately positioned in 3D space - yet Microsoft has essentially made the same pitch with its own hardware, which also has the HRTF support that the Tempest Engine has. Microsoft hasn't made any specific promises about mapping 3D audio to the individual's specific HRTF, but then again, Sony hasn't really told us how it plans to get that data for each player. I'll be interested to see how this all shakes out once the consoles are out and software is available.

Overall, beyond some interesting specifics - and the reveal of the Scarlett processor die shot - a lot of what the Hot Chips presentation covers was all part and parcel of the March reveal event we attended, but the insight into how economics has played a role in shaping the design is valuable. Not only that, but Microsoft's work with the Xbox Velocity Architecture and DirectStorage will transition across to PC too. In fact, the arrival of the DirectX 12 Ultimate API seems to be rounding up a lot of next-gen innovations found in Series X and ensuring that the PC platform does not get left behind. Microsoft clearly feels it has stewardship of innovation beyond the Xbox console alone - and it's a responsibility that Sony doesn't really have to concern itself with, perhaps explaining some of its more exotic design choices.

As a journalist, what I've enjoyed about the initial Series X tech reveal and the Hot Chips presentation is how transparent Microsoft has been about the capabilities of its new machine, how it was put together and why. Nobody talks about 'secret sauce' or hitherto undisclosed game-changing features with Xbox because it's all out there in the open - something I can confirm having also taken a look at developer documentation. This is Xbox Series X and we now know everything Microsoft has cooked up for its new machine, and I do wonder if Sony will follow suit - perhaps starting with the hardware teardown Mark Cerny talked about in his Road to PlayStation 5 presentation. That said, while spec discussions are interesting, perhaps the conversation has moved on to other matters - like what games we'll get to play in the launch window, and of course, just how much it'll cost to buy into the next-gen dream.