Dark Souls 2: The difficult second game

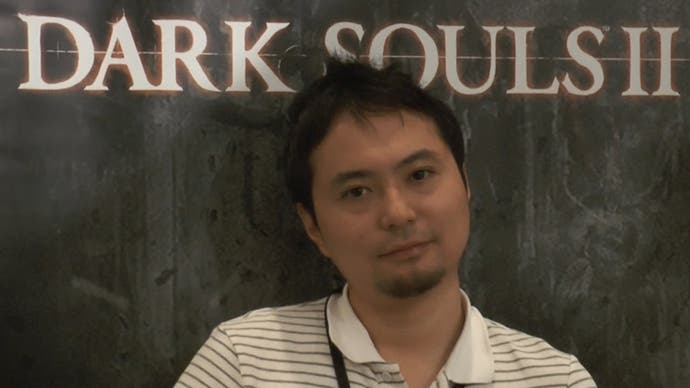

A fireside chat with director Yui Tanimura.

Yui Tanimura has a degree in psychology, which, in the context of his childhood dream to become a professional baseball player, could be considered a failure and, in the context of his subsequent career as a video game designer, could be considered irrelevant. And yet, it's training that has served him well in his current task: crafting the sequel to From Software's unlikely 2011 hit, Dark Souls. For one, his background has provided him a few theories on why that curious game, which so forcefully eschewed mainstream fashions with unrelenting challenge, unfashionable style and a mere whisper of a storyline, has sold more than 2.3 million copies to date.

"It's about the satisfaction of overcoming a challenge," he says. "When you see somebody clenching their fist in happiness at some victory over defeat: that is a peculiarly human reaction. And it's something that games are well placed to tap into. People claim that Dark Souls is a difficult game, but the difficulty, if you want to call it that, is only a means to amplify the elation."

The 'difficult' tag - if you want to call it that - has long been attached to Dark Souls and, if early demos of Tanimura's sequel are representative of the whole, will be similarly and somewhat unthinkingly applied to its sequel too. But it is something of a misnomer (even if it's one perpetuated by the original game's accompanying advertising campaign, which issued the bleak warning: Prepare to Die). But in truth Dark Souls' character is one of unrelenting fairness. The feeling as you set out time and again to penetrate a little deeper into Dark Souls' world with its cliff tops patrolled by skeletons and valleys guarded by hydra is one of banging a weak fist against overwhelming odds. But this is a game that simply demands its player improves their skills in order to progress - and the rewards for those who persevere are as lasting as the muscle memory gained along the way.

Fairness is, for Tanimura, another of the game's psychological lures. "If people talk about difficulty it's crucial that it's never discussed in terms of, say, the control scheme or the character not doing the things the player wants it to. That kind of 'difficulty' leads to pure frustration." Rather, Tanimura says, the player must understand that failure was only ever due to his or her own poor decision-making. "It's that knowledge that keeps a player going," he says, "alongside the chance to go back and make better decisions. Understanding that changes the way in which we design the game. We're designing to inspire players to make poor decisions. That might seem perverse but it is where the game's power is found: anyone can play and succeed, regardless of natural talent. They just need to pay attention."

Tanimura, who is just as softly-spoken as his mentor, Dark Souls creator Hidetaka Miyazaki, from whom he's taken directorial duties for this sequel, is not the usual corporate Japanese video game maker. He grew up in Saitama, just north of Tokyo, and unlike so many of his contemporaries, he didn't harbour dreams of pursuing a career in manga, nor did he dream of making games for a living. Neither was the job offer for a design role at From Software, the Shinjuku-based studio at which he's worked his entire career, his only option. "I had a number of offers on the table when I graduated," he says. His decision to work in video games was driven by passion, not financial ambition. As a teenager, Tanimura had played and loved From Software's dark fantasy PlayStation game, King's Field. "At the time I thought From Software was a Western company because of that game's art style," he says. "It was only while reading a newspaper when I saw the company advertising a job that I realised From Software was Japanese. The opportunity to work at the studio that made King's Field was irresistible to me."

Despite having no experience making games, either at school or as a hobbyist, Tanimura was offered a job shortly after his first interview. "From Software is a unique company," he says. "It often hires people with no experience in the game industry at all. It's not what's on your resume but how you think that matters. I joined completely fresh to the industry. Perhaps it was the way I spoke, or the way I thought. Regardless of what it was, they saw something in me that fit." After joining Tanimura, described by his colleagues as a 'workaholic', worked on a wide range of titles, from Armoured Core to Shadow Tower. But it wasn't until he completed his third project that he felt certain this was the career for him. "That was probably the point at which I thought: as long as I keep my endurance up, I can probably last the distance in this industry."

"I try to be deeply cynical in terms of the things I put in the game. I'm not only interested in creating things that players will enjoy, per se. I also want to include stuff that is somehow iffy."

While his previous design experience might appear at odds with Dark Souls' idiosyncratic approach, Tanimura believes it's been key to his promotion to the role. "I've made games my entire adult life," he says. "There have been successes and failures, like most people who make games. But, you know, I feel like all that experience has been leading up to this experience. Working on different styles and genres of games is invaluable. Even Miyazaki-san worked on other types of games. It's this variety of experience that ensures you make sound decisions. Without it I'd be in trouble."

Miyazaki casts a long shadow over Dark Souls 2. The news that the esteemed director - a man who, during Dark Souls' development kept a digital photo frame on his desk which cycled through fan criticisms of his previous project, Demons' Souls, as an incentive to work harder - would not be directing this sequel was met with consternation from fans. Tanimura's challenge is to meet the expectations of the vociferous fan base, while adding his own character and imprint to the world and the systems that fire it. "Miyazaki and I are different people," he says, "so of course we direct in very different ways. I want to put my own personality into the game where possible and I actually think the game is a strong reflection of who I am, and what I'm interested in. Not only in games but also in my approach to life. But I'm mindful of the Dark Souls essence. Conceptually the two games are close, but it's important to be different too."

Tanimura begins to speak psychology again. "Of course we must stay true to the Dark Souls core. People expect that. But to only do that in our design would be disastrous. Players, whether they admit it or not, want to be surprised by a video game; they crave novelty. So a great deal of my work is thinking up new things I can implement to surprise the player, while at the same time remaining true to the game's lineage." This is a problem faced by every game director on a well loved and, by definition, well-worn video game series: how to introduce the new without losing that which led to the original's success.

For Tanimura, the challenge is increased thanks to the fantasy aesthetic, a haunting and haunted netherworld of chinked cobblestones, crumbling clock-towers and knights in tarnished armour, all of which long predates the series in the cultural consciousness. "Castles and fortresses are a classic example," he says. "This kind of stuff has been done so many times before. So the fun and challenging part of the work is to work out how to play on these tropes, to make them surprising and exciting again."

But beyond the raw assets, Tanimura is eager to mess with players' minds in other ways. "I try to be deeply cynical in terms of the things I put in the game," he says. "I'm not only interested in creating things that players will enjoy, per se. I also want to include stuff that is somehow iffy. It's also about challenging expectations and not necessarily giving people what they want. That, in a way, is the essence of Dark Souls: upsetting expectations."

Dark Souls' financial success has injected From Software with new talent, many of whom must help Tanimura solve these pressing questions. The team is no less than 50 per cent larger than the one that worked on Dark Souls, and just staying connected to his network of designers, artists and programmers takes up the bulk of Tanimura's time. "I spend most of the day speaking to my team," he says. "I have to do that before I start on my own work, which sometimes I can't do till the early evening." Perhaps because of this attention, Tanimura appears to be a well-liked leader in his bulging team. "I afford a lot of freedom to my artists and staff," he says. "I want them to be creative. Of course, I give them certain boundaries and rules, but as long as they stay within those they are free to do whatever they want. Some artists work better when they are totally free. Others shine when they have close direction. You have to adjust your leadership according to the individual, I think."

While Tanimura's singular vision for the game is clear, he, like Miyazaki before him, is not beyond listening to and acting upon player feedback. In Dark Souls 2, for example, players will be free to warp between the bonfires that provide rare points of safety in the cruel world from the beginning of the game, a feature only unlocked in the latter stages of Dark Souls. The team is also overhauling how the online component to the game works, whereby players are able to invade one another's worlds and do battle against one another. "In the first game some people didn't want to be invaded at all, and there were others who wanted to be attacked regularly," he says. "We're still wrestling with these questions. One thing that's certain though: we want multiplayer to be more understandable to people this time."

The storyline, however, will remain opaque. In contrast to the video game medium's current blockbuster narratives, usually spilled in expensive cutscenes that strain to mimic cinema, Dark Souls was a story told through stutter and landscape. "This isn't going to change," Tanimura says. "Our stance on storytelling at From Software is not in the cinematic drama style that explains a story from A to Z as if the game was a movie. We focus on allowing the player to make their own discoveries, to prod at the universe and see what they can freely find. We are strong believers in this way of telling stories in video games. Our stance has not changed."

As Dark Souls 2 enters the final development strait (the European beta, during which the game's online integration will be tested, opens this weekend) Tanimura is working harder than ever. What does his family think about it? "I think, right now, they wish that they could see me a bit more," he says. And what do they think about the game?

"My family doesn't play Dark Souls," he says, rather mournfully. "They say it's too hard."