Chrono Trigger

If I could turn back time.

Is the chance to play with time gaming's greatest gift to players? It's something no other entertainment medium offers and yet, when we rewind the last ten seconds of Prince of Persia, un-jumping a mistimed leap, it's the most natural thing in the world. In Race Driver GRID, a 150mph collision can be undone in an instant, fenders uncrumpling, engine rebuilding, broken faces rearranged with the squeeze of a trigger. In Braid, time can be inched forward and back, millisecond adjustments that solve four-dimensional puzzles impossible to experience outside of a videogame. And yet, with all this power - the power of a time lord, the power that inventors have hungered for throughout history - all we seem to use it for is fixing our petty mistakes.

Chrono Trigger's time-manipulation has a higher purpose. Here you hold in your hands a seismic force, one whose mastery can bring about wars or avert them, can wipe out entire lineages or birth them, can right the wrongs (or wrong the rights) of generations. It's a power that gives rise to new futures. In this world, a trivial act of kindness 600 years in the past changes the landscape of the present immeasurably, and you can be there to see it happen. And yet time travel is just the first of a hundred different ideas that make Chrono Trigger the greatest Japanese RPG ever made.

Released toward the end of the genre's golden age on the Super Nintendo, Chrono Trigger brought together Square's "Dream Team" of Hironobu Sakaguchi, creator of Final Fantasy, and Yuji Horii, creator of Dragon Quest, flanked by stars such as renowned anime artist Akira Toriyama and composer Nobuo Uematsu. Together they set to work on a JRPG that, in many ways, is nothing like a JRPG.

To begin with, the team kicked away the genre crutches that so rile its haters. Gone are the random battles, the tedious level grinding and the drawn-out battle animations. In their place, a breezy kind of combat, closer to Link than Cloud. Now you're free to visit the final boss at almost any point, ending the game whenever you're ready to be rewarded with one of fourteen different endings. Gone is the tedious, overblown storytelling, replaced by a tale told in the straightforward vocabulary of a classic children's book. The game's dialogue is universally accessible, its themes universally understood, its fantasy grounded in that truth that makes a good story a classic one.

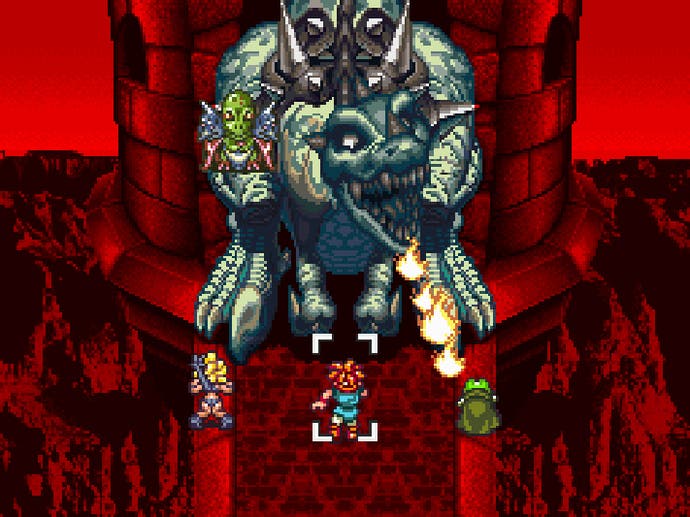

The game opens in 1000 AD, introducing players to Crono (so named because removing the 'h' freed up much-needed cartridge space in the SNES original, although you can now rename him). Crono's best friend, science nerd girl Lucca, has invented a teleporter that, when tested for the first time, turns out to be a time machine. The duo travel back and forth between seven periods, building a ragtag team of friends drawn from as far back as 65 Million BC all the way forward to a post-apocalyptic 2300 AD. Together they fix the mistakes of the past, watching as their butterfly wing actions turn history-making tornadoes across the millennia.

The game world is small in terms of geography, so exploration is carried out in time rather than in space, a fascinating shift for a genre normally obsessed with travel. The themes of cause and effect characterise not only the main quest but also the side missions. For example, in Crono's time period, a greedy and foolish mayor runs the bustling port of Porre. Travel back in time and you can speak to one of his ancestral mothers. During this encounter you're given the option to give her an item for free. Do so and she vows to always bring up her children to believe in kindness and generosity. When you next return to Porre you'll find the mayor is now a charitable man, and his port is far more valuable than it was before. This wide-angle examination of cause and effect, always videogaming's primary theme, is mesmerising, even if it is sometimes over-simplistic and, necessarily, idealistic.