Birth review - a deft and creative exploration of loneliness

Habeas corpus.

In Madison Karrh's new point-and-click game, birth follows death. You are lonely in the city, so you wander about, finding bones and organs and then using them to construct a makeshift friend. It would be a Frankenstein story, if it ever felt even slightly gothic. Instead, it's so much better. It feels strange and personal, like being privy to someone's daydreams. Birth follows death: this has the backwards logic of daydreams for starters, topsy-turviness echoing out and finding purchase and expression in the ways that the stuff of the game - feathers, dandelions, pottery pieces, bird skulls - are both worthless and also sort of priceless in the right hands, and in the way that your ultimate goal is both impossible and heart-rendingly essential.

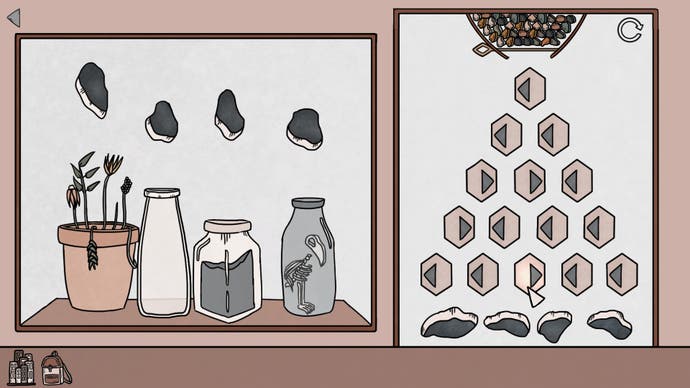

Birth is almost wordless. It's hand-drawn with confident black lines, a restrained colour scheme, and a deftness when it comes to the wizened, broken and deserted. Old wrists, empty teacups, laundry silently tumbling in a dryer. It's a puzzle game, I guess, although it's too thoughtful, too thought provoking, to ever settle into a single genre for long. It's a reminder that beneath genre every game is ultimately itself, existing in a genre of one. You earn your bones and organs by playing dominos, completing jigsaws, mastering hex games and even doing a little inventory Tetris. Not all the activities have such clear logic, though, and that feels like a strength here. Birth is ready to bypass logic and meet you somewhere a bit deeper.

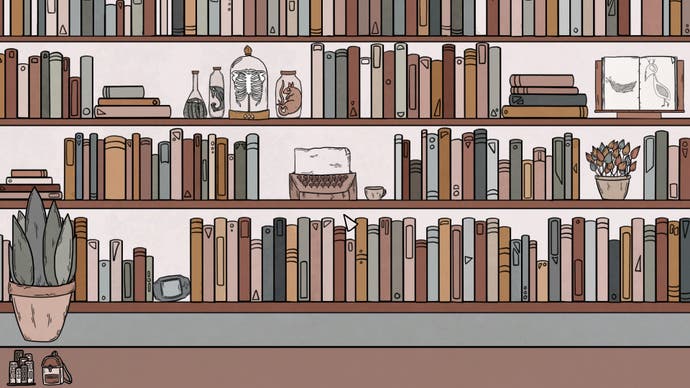

You get to piece together the contents of a fish tank, and nose through the shelves of a bookcase. The actual games you play in Birth always feel secondary to the sense of exploring, or perhaps prying is closer to it - looking through other people's stuff, prodding at their private worlds as if they were a collection of Activity Bears. At one moment - my favourite - I pressed the keys of an old manual typewriter and plants grew from the chattering innards of the machine. It now feels like a rare failing in manual typewriters that they don't all do this.

That stuff, though. Birth is made of the things children might have in their pockets after a fruitful day in the woods: mushrooms, buttons, torn scraps of paper and weeds. The game is made of fragments, and so often what you're doing is finding the scattered fragments of something and putting it back together. That's a puzzle in a puzzle, really: restoring an object, and being rewarded with a part of the living object you ultimately hope to restore yourself.

These discrete puzzles are slotted together in the various parts of a city, drawn in ancient textbook sepia, face-on, like an Ellen Raskin illustration or a New Yorker cover, that you ghost back and forth through, visiting the library, the bakery, the art studio and onwards. If this were cinema, it would be an endless lateral tracking shot, the spookiest and most questioning of all camera moves. If this were a book itself, the pages would be thick, the edges warn away to cottony softness. There might be inverted starbursts of mold.

There are other people in these places you visit, as hollowed out themselves as the shucked skull of a pomegranate that you can explore in one quietly magical sequence at the very heart of the game. You are doing these people favours - or are you? There is a sense, generally, of being an invisible force here, and sometimes of simply being beneath noticing.

The soundtrack is mournful and unsettling. There's a version of Holst's I Vow to Thee, My Country that sounds like it was recorded at midnight in a haunted storm drain. Bees seem to buzz over an organ treatment of the Gymnopedies, and elsewhere there's a funereal shopping mall rendition of Beethoven's Seventh, one of his more doomy works in the first place. The music always feels to me like it's being played elsewhere, like it's intended for another audience and only bleeding through thin bedsit walls. As such it works with your task, with the surroundings, with the careful lack of concrete embodiment, to create a game that is rendered stark by a penetrating kind of absence. This is a game about loneliness of course - you are making yourself a friend - but it has an understanding of the chill texture of loneliness, modern, urban loneliness, that is astonishing to me in its clarity and compassion.

Where will Birth take you? I would love to know. It took me, quite involuntarily, back to a moment over twenty years ago when I returned to the town I grew up in during a break from university. I wandered the streets and felt not just lonely but invisible - the somewhat freeing, somewhat weighty invisibility of Birth - because I knew that I knew nobody here anymore, that my acquaintances were all scattered, and so was I, really. I was in a place where there would be nobody to recognise, only familiar things.

It takes me back further too, and I think it's intended to. Karrh, the ingenious creator of Birth, is also the designer of a number of other unsettling, searching, empathetic games. This may be her most potent, her most delicate in its probing. Many times over the course of Birth, you are called upon to put bugs back together or sort stones. These are games a child could play, and the more I played, the more I began to suspect that this is a crucial aspect of the entire thing. Loneliness in adulthood is all the more painful when I've experienced it, because it reminds me of being lonely as a child. These are those rare, vital experiences where adult life and childhood overlap, and where we can move, without casting a shadow, between one mode of being and the other.