"Words and images are our main things": Where does a game like Mothmen 1966 come from?

Behind the scenes with the Pixel Pulps.

It doesn't take long in a conversation with the people behind LCB Game Studio for them to start recommending books. The two-person team is based in Argentina where they make the Pixel Pulp games, ingenious and quietly literary visual novels with that splinter of shock and spooky sensationalism that would have made Walter Gibson very happy. Writer and game designer Nico Saraintaris tells me he is proud of Argentina's literary heritage. So, have I read Mariana Enriquez? I haven't! Are the translations good? Where should I start? In return, I recommend Maria Gainza, another Argentinian writer, whose Optic Nerve is a dazzling book about memory and art and life in Buenos Aires. I've read it once and I'm already itching to read it again. Pretty soon we're busy writing down recommendations while the Zoom call transmits nothing but images of heads bowed over notepads and the brisk scratch of pens and paper. It feels, I have to admit, exactly as I had imagined this conversation going.

I've wanted to talk to Saraintaris and his colleague Fernando Martinez Ruppel (Instagram bio: "Illustration, pixel art, music and paranormal activity." Perfection.) after being completely beguiled by their game, Mothmen 1966. Pixel Pulp to its core, Mothmen isn't just a videogame about the best of all cryptids. It's a piece of interactive fiction that presents itself as part otherworld mystery novel and part long-lost CGA adventure game, right down to the gloriously lurid four-colour art and the text-selection interface with its chunky throwback fonts. It's a game to go into knowing as little as possible. Wait until night. Make some really, really bad instant coffee, preferably burning it in the process, dim the lights until the room is lit only by the Pentium monitor and the sickly sodium glow of streetlamps and lose yourself in this weird and brilliant thing.

Oh, and I wanted to apologise, too, because while I knew I liked Mothmen when I wrote about it last year, I did not yet realise how much I truly loved it. I did not know how much, over the months to come, it would return to me at the strangest moments and nudge all other games aside in my imagination. The harmony of it! It's a game about a haunting, and it's haunted me. It's a game about living with old soft-edged paperbacks, and it lived with me. It's heartfelt and so clever, so carefully made. It feels like a game - this is the only way I can put this - that breathes out into our world. It's like going to bed on a still night with incense burning and having all manner of intriguing, troubling dreams.

What a thing. I played through Mothmen again prior to chatting to the team and realised, for example, how transporting the text select interface truly is. You use it for everything, even an in-game solitaire variant. I thought it was cumbersome when I first played it, but now I realise I had entirely missed the point. This game offers players a specific way of entering its world, and everything is channelled through that. It's a control scheme employed as a kind of air lock.

Okay, enough analogies. So I got Mothmen a little bit wrong at first, even if I loved it. One thing I did understand even back at the start, though, was that a game like this must come from a place of deep memory. Is that right?

"My idea when we made these games, I have very fond memories of playing PC Games with my mother," says Ruppel. "When you grow up with your mother, I never think of her as someone cool, but now when I look back, thinking of her as a young woman, playing videogames with her son, it was cool. And it's one of the main motives I have for making games. I want to bring some of that kind of thing back to videogames now. That's one of the reasons why I choose pixel art and that whole aesthetic. I like the noise that you find in pixel art. I mix a bit of comic books in with that.

"But I think that nostalgia, that's what I want to bring to the table, knowing what Nico can do with writing. It's thinking of what I can bring to younger people, having those pixel art games in your house."

"My grandfather was very fond of computers," says Saraintaris, picking up Ruppel's thread with the ease you get with people who have worked very closely, very intently together. " I remember mostly things like the Spectrum, having cassettes and waiting for them to load. I remember all those games, and I remember that time before genres were ossified, and you have all these programmers creating stuff. So if you have an idea you can create whatever you want without those [genre] constraints." He pauses, before refining his thought. "I love constraints, but I think they can be bad if you don't know how to work with them. For me the eighties and late seventies were like this, an area where everything was exploding."

I wonder if this desire to work beyond genre, to use memory and unusual art styles and private passions made public, I wonder if that's why a game like Mothmen is so immersive. I know we misuse this word terribly - anything with a huge map and lots of mission icons must be immersive because, hey, it drops you deep into the ocean, right? But a game like Mothmen strikes me as being a very pure and unforced form of immersion. That dream you dream alone on a night with clear skies and a full moon. You climb inside a game like this and then as you try to understand how it works, how it tells its story and moves from one scene to the next and throws a bit of interactivity your way, and as you muddle through all this, it feels like the roof seals up above you and you're right inside it. So how to turn that into a question? Is there a point when making games like this, with the unusual interface, the art style both familiar and strange, and stories that draw on a beautifully lurid pulp tradition, with monsters and midnight journeys and ulterior motives, is there a point where this all comes together, the layers of it, and gives you a game that feels this rich and distinct?

"When we started working on Pixel Pulps, we started working before on another project - this was 2018, 2019 - on a much bigger project," Saraintaris tells me. Then the pandemic came and everything fell apart. Or did it? "We've been working together and making games since 2012, and we have a publishing label together, with just one book," Saraintaris explains. "When all this happened with the pandemic, we decide to take a step back and just see what we think we were kind of good at when we started working together. Words and images are our main things that we think we can do stuff with. The previous game was a really complex, really weird game. It got some attention and we got excited about making it, but it was bigger than the thing that we knew we could be good at. It was maybe too much."

So the duo started thinking of something smaller they might make. "Just the two of us," says Saraintaris, picking up speed. "We chose the interactive fiction genre, or visual novel. We're writing pulps, and we really like alliterations, so Pixel Pulps started as a joke and then it stuck. Then we start to build on it."

And all of this fed into what the game would become. "The way we work is pure intuition," Saraintaris explains. "We decide on something and we keep pushing. So there's this beautiful idea, from a writer in Argentina who is one of my favourites, César Aira: if you're going to flee from a battle, you should flee not backwards but forwards." A pause to let that thought hold the air. "This idea of fleeing forward! So he doesn't correct his fictions - he has editors who read what he writes, but his idea is writing every day and you write some pages every day and after some time you have something."

Arms crossed. "So that's how we work, and because we're not editing too much we have to write more in order to correct and not erase - so that's where the layers of the game come in. So maybe we decide to write a scene and maybe it sounds great, so we write it and illustrate it, but after some chapters, it's not what we thought about initially, so we start correcting the background and context to make the scene better." He pauses again. "So that's mainly our creative process - it's messy, but it works for us. It's the way we are able to do lots of stuff, so we're really fond of it."

"One of our main objectives was having this pulp ethic, but bring it to videogames," continues Ruppel. "So in traditional development it sometimes takes one, two, three years. We like that kind of process, but we know that we will get bored if we spend so much time on just one project. Now we're talking about our next project and we have three ideas and we want to make them all. To keep that kind of energy, we wanted to make the games fast. It's trusting each other a lot when we work. I make all the pictures, Nico, he makes the puzzles, and writes. Once we have that all laid out, once we've made all that, I make a pass with the videogame, play it back-to-back, and take notes: this moment needs sound, this moment needs some kind of highlight, and start working from there. The only feedback I get from Nico is when something isn't working. He's like my guinea pig of sound when working. If it doesn't sound good, I know he's going to tell me. It has a flow, I think. That's what I like."

I hadn't realised how deep the pulp ethic goes, in other words. It's not just the subject matter, but the way the games are actually produced. LCB are cranking on games. So sure, you can be Thomas Pynchon and spend a decade or more on a book, and write eight, nine, ten in total. You can be Ralph Ellison and write one and a half novels, all told, all classics. Or you can be Walter Gibson, cranking on The Shadow, fingers calloused and bleeding on the typewriter, turning out a pulp every month - and there's a vividness that comes with that. The process filters into the work. The pace and the know-how becomes a kind of watermark.

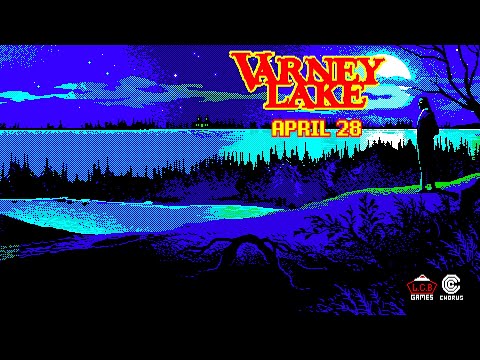

And that's the thing. Mothmen 1966 still feels like the new game from LCB Studios to me, but just before we chatted over Zoom, I got an email about the team's latest game, Varney Lake, which is out later this month. Another Pixel Pulp, with a few threads continued from Mothmen 1966, none of which should be spoiled. The same CGA art, the same preoccupation with Solitaire variants, the same love of the creepy, the half-seen, the whispered. I can't wait to turn off the lights one night and properly play it.

And it comes from the same place, too. "We like work ethic - like having a trade," says Ruppel. "Working, Nico as a writer, me as an illustrator, always having to deal with deadlines, working with ideas from other people, you get this kind of practice and this ability to work fast.

"If you're working on something of your own you tend to take more time and take care of it like it's something precious. I like making things not as something precious but as..." A final pause. How to put it? "...As a discharge of creativity."