Why people are still making NES games

It's DIY or die.

Officially, the NES died in 1995, some nine years after its launch. Unofficially, though, dedicated fans are keeping Nintendo's retro console very much alive.

Today, the most prolific and respected NES developers are people such as Kevin Hanley, from Crestview, Florida. Since 2009, Hanley has made nine "homebrew" NES games, cartridges and all. His catalogue is an eclectic mix of remakes and originals. His first game was Ultimate Frogger Champion, a port of the original arcade Frogger. He spent much of 2015 on The Incident, an original block-pushing puzzler. Earlier this year, he released his port of Scramble, another staple of '80s arcades.

"I thought it would be fun to bring other games that I grew up playing on other systems over to my favorite system," Hanley says. "More of a challenge, but also just because I love them and I want more people to play them."

Hanley strives to deliver authentic experiences with all his games, so he stays close to his source material. "When you start changing things like speeds, or points of the game in general, I think it takes away from it a little bit," he says. "So I try to be faithful for the most part, but I try to throw in little twists or additions where I can."

Hanley's sprucing doesn't affect gameplay. The achievements he added to Scramble, for example, incorporate classic challenges such as hitting score milestones and completing the game without dying. Still, some tweaks are more noticeable. A former competitive Frogger player himself, Hanley became unsatisfied with his original port of Frogger as he grew more NES-savvy. So in 2016, he retooled Frogger for a four-in-one game pack, not only fixing bugs but also adding custom sound effects, a new sinking animation for the game's iconic turtles, and a more sophisticated score counter.

The NES hasn't changed, but board and memory technology has improved immensely in the past 30 years, enabling NES homebrewers to wring a little more out of games without relying on ROMs or emulators. Building save systems is much easier, for one, and advances in flash memory allow Hanley and other creators to add in modern features such as achievements.

But then, why the NES? Why go out of your way with bells and whistles when you could just developer for a more powerful retro system? Surely even jumping to the SNES would greatly expand what you can do.

Actually, that's exactly the problem.

"Once you start getting more modern than the NES, stuff like the Super Nintendo, it becomes way, way more complicated for a single person to tackle everything," Hanley says. "I think the NES is sort of right on the cusp of one person actually being able to develop all aspects of a game in a reasonable amount of time."

Because the NES is just simple enough, Hanley is able to make games with minimal outsourcing while spending an average of six to eight months on each project. And aside from nigh-unrivaled nostalgia, the NES does have other things going for it as a homebrew platform. Its dated format poses a challenge that demands ingenuity, routinely resulting in ingenious games.

"Because it has some pretty strict limitations that you have to follow, people are being really creative on what they can do to make things look as good as they can," Hanley says. The best homebrews straddle the cutting edge of NES tech and redefine what's possible with 8-bit sprites, sounds and scrolling.

Aside from techniques such as dithering, which uses precisely peppered pixels to mimic shading and textures not technically possible within the limited NES colour palette, NES homebrewers have also advanced sprite composition. NES visuals are built on sprites that are always eight pixels wide, but can be eight or 16 pixels tall, with the latter effectively resulting in a bigger game screen. (The original Super Mario Bros. uses 8x8 sprites, for example, whereas Super Mario Bros. 3 uses 8x16.) Ordinarily a game's sprites are sized with hardware limits in mind, but small improvements here and there have let homebrewers create more varied assets in 8x16 without running into issues with flickering or scroll speed, allowing for more unique art.

NES homebrewers also benefit from a robust supply market. For years, Hanley explains, retro game retailer RetroUSB was the only reliable source for NES cartridges and boards. And while they're still everyone's go-to, other suppliers have cropped up, bringing prices down and making appropriate quantities easier to purchase. However, building a cheaper and more approachable market had the unintended side effect of attracting cash-in shovelware devs, which put a damper on the niche market's enthusiasm. Hanley has felt the effect of this himself: he's only sold around 100 copies of Scramble, compared to the 200 to 300 units he moved with previous projects.

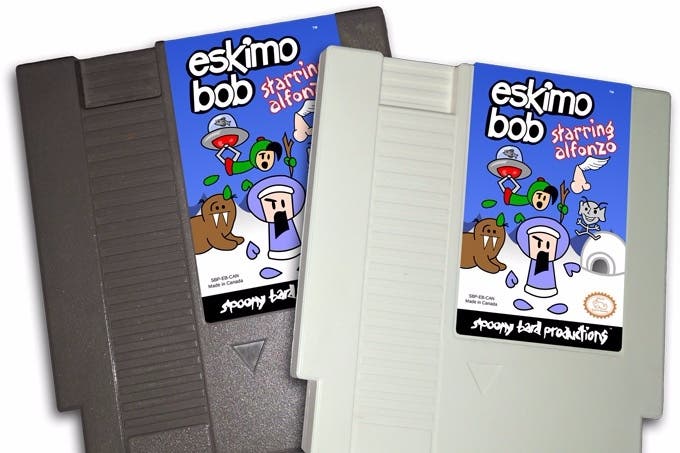

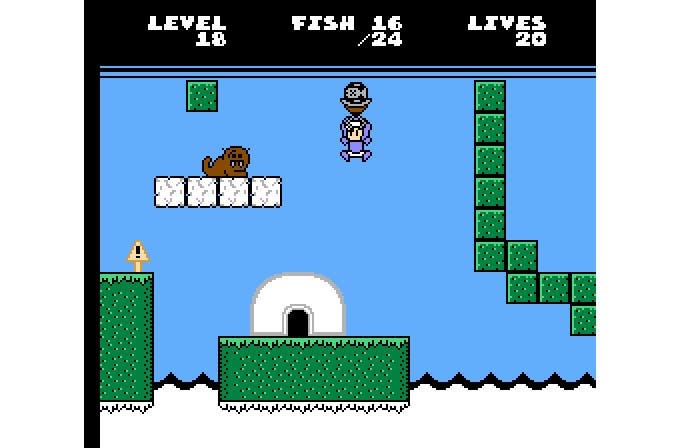

Nevertheless, new NES games can still draw a crowd. In February 2017, Tomas Guinan, from Truro, Canada, decided to try making his own. Guinan experimented with NES ROMs and localisation in the '90s - even going as far as to singlehandedly translate The Glory of Heracles 2 - so he already had some knowledge of the system's innards. Plus he wanted a unique portfolio piece to help him break into game development as a career. Three months later, he'd made Eskimo Bob, a 2D platformer designed for the NES.

Eskimo Bob was originally a Newgrounds-era flash cartoon series made by a teenage Guinan and his brother. The pair had long joked about turning it into a game for their favourite system, and thanks to some prior experience and plentiful tutorials, Guinan was able to do that with relatively little trouble. But he wanted to go further, not for his portfolio but for his dream.

"Putting it on cartridges was the passion-driven part," Guinan says, "where just the idea, ever since I was a kid, of making a NES game and having it on a cartridge that I can put into actual hardware and play... it's something that the little kid inside of me thinks is incredibly cool."

Even for a first-timer like Guinan, putting an NES game on a cartridge was a fairly simple process. "I've got someone who's going to print out the boxes for me, and I'll have to fold those together myself," he says. "I'm basically getting a bunch of the raw materials. I'll get manuals, labels and boxes shipped, and I get the cartridge shells and boards from another supplier." Thanks to his Kickstarter, he was able to save time and money by ordering in bulk. From there, he just has to "screw them together and ship them out."

Capturing the spirit of the NES through games like Shovel Knight is great, Guinan agrees, but there's something special about truly preserving the form. "The best thing I can compare it to is when bands do a limited release of a new album on vinyl," he says. "And they might only sell 300 units of that, but it's something their hardcore fans love because it's tangible and they can hold it, and it's something that's a completely different experience than downloading them off iTunes. I think it's similar to that, where it's more about the feel than the actual product itself."

With his game finished, Guinan turned to KickStarter to fund production. At the time of writing, Eskimo Bob's campaign has raised nearly triple its goal of $5200. There's clear demand for new NES games, and many are eager to provide them.

Antoine Gohin is a French indie dev who was also attracted to the simplicity of the NES. He started learning to code for the system in 2015, and within a year could produce presentable prototypes. In September 2016, he entered a NES coding competition with the help of an NESdev community member. Not only did their prototype win the competition, it went on to become Twin Dragons, another super-funded KickStarter darling promising the full NES package and packaging - and, strikingly like Eskimo Bob, a 2D platformer with two playable protagonists.

"The challenge here was really to create a NES game in all aspects," Gohin tells me over email. "If I wanted to make a PC retro-like game, I wouldn't bother learning all the NES architecture and spend months coding for it. I could have used modern tools like Unity or GameMaker. No, the idea was to make a game I could put on a cartridge."

NES homebrews like Eskimo Bob and Twin Dragons do far more than exploit nostalgia. They extend the life of one of the most important consoles in history, promote the creative spirit born of limitations and often allow their creators to realize lifelong dreams. And perhaps most importantly, they're still evolving.

"I think, in the coming years, you'll see some more exciting things coming out with some online NES stuff happening," Hanley says. "We're just trying to do things that have never been done. We're looking ahead to see what we can do that they didn't think about 25 years ago. People look at games differently now... we have to take what modern games look for and try to cram it into 512 kilobytes."

The future of NES development will be shaped by wild ideas like online play, something Hanley is experimenting with himself by way of Unicorn, an online RPG. Repeat: Unicorn is an online RPG for the NES. And Hanley says the game itself is done. Now he and another developer are finalizing the external adapter that powers its online functionality.

Others are also hard at work developing features that, by all rights, the NES was never meant to have. A big one is raycasting, the rendering method behind first-person games such as Wolfenstein and DOOM, which has long been capable of running on NES hardware. As is the case with all homebrew NES games, now it's just a matter of getting technology to catch up with ambition. That, and making it fun.