Why Below has taken half a decade to make

"Making a game is obscenely challenging."

"Making a game is obscenely challenging," Nathan Vella, boss of Toronto, Canada developer Capybara tells me over the phone.

"It's a little bit physically challenging, but it's always mentally challenging. Making a project pushes you. The metaphor I always use is - I don't know if you've ever been to the desert or somewhere ridiculously hot, and you're standing out in crazy warm weather, it's 35 degrees and you're like, oh my gosh, it's so hot! But it's a warm hot, so you're like, okay, I can kind of deal with it, and you're used to it not being this hot so you think it's kind of nice, and you acclimate yourself to the ridiculous heat in a desert.

"Having a five-year project is like putting a giant magnifying glass between you and the desert and the sun. It makes everything so much harder. It makes every problem so much bigger. It requires so much dedication and commitment from the team just to keep moving forward and past a certain point. It's really disappointing to delay games. It's really disappointing to miss deadlines. But at the same time, nothing is more disappointing than putting out a game you're not happy with and aren't proud of and can't speak honestly to players about."

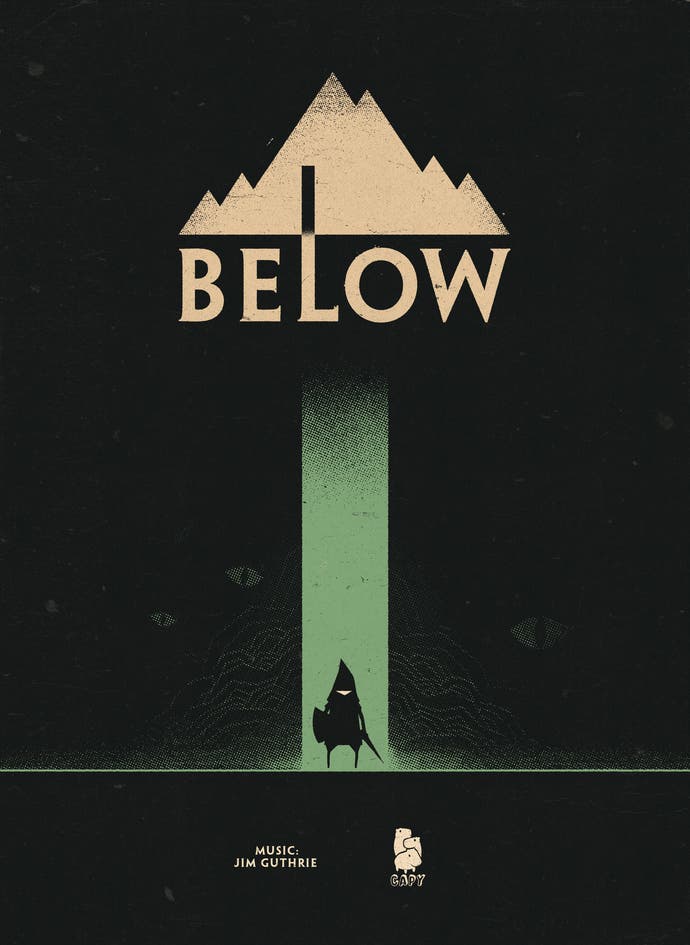

Vella is talking about Below, a game Capy has worked on for over five years. The roguelike survival procedurally-generated dungeon crawler with a zoomed out perspective and a tiny warrior was announced in 2013 during Microsoft's E3 press conference, and has been delayed multiple times. At one point, it felt like Below might never come out.

But Below, Capy insists, is coming out this year, in 2018. That's good news for people looking forward to playing the game, but it's even better news for the developers, the people who have spent every day for five years trying to make Below work, trying to make it the best it can be.

Clearly, Capy has run up against significant challenges in the development of Below. As Vella tells me, no-one wants to delay a video game, and no-one wants to spend half a decade making one. But what kind of challenges has the team faced? In short, why has Below taken so long?

Vella, who is happy to discuss the problems Below has thrown up, says the team spent a lot of time trying to work out whether the game was more than the sum of its parts. That is to say, trying to work out whether combining Below's mechanics and systems made for a fun experience.

"Every one of the major pillars of the game - the scale, the perspective, the systems, the combat, the goal of creating interesting exploration - all of those things, we did them," Vella says.

"They were there. And then it was the question of self-reflection as a developer, like, is them just being there good enough, or is there somewhere else this game could go?

"The way our creative director and the game director Kris Piotrowski talks about it is like, we were actually excavating the depths as we were making a game about the depths. You find a lot of stuff along the way."

Below has turned out to be a much bigger game than Capy intended. Now, with the benefit of hindsight, Vella regrets announcing the game in 2013. "We thought it would be cool to announce a game a little bit earlier and bring some fans along for the ride," he explains. "We totally understand it was too early." Then, though, Capy didn't see the problem with announcing the game. Then, it was nowhere near as big as it is now. "It's a big, long, weird game we didn't necessarily expect to make."

Back then, all those challenges Capy ran up against had yet to present themselves. Indeed, Capy didn't think Below would suffer such a tricky development in the first place. "It's not one of those shit happens scenarios," Vella explains. "It's one of those, we made a whole bunch of choices to try to make the game as good as we can after a certain point. Once you've delayed it once, you may as well do what you need to do to make it great, because a delayed game that still comes out crappy is not really going to be okay by us, by any means."

When Capy last delayed the game - in 2016 - it sounded like it had done so indefinitely. There was a negativity associated with the delay and Capy's accompanying blog post. It suggested, at least it did to me at the time, that Below might never come out. It was quite a depressing delay announcement to read, as someone who had high hopes for the project.

At the time, Capy was conscious of the risk associated with telling people Below would come out at a certain time, or even a specific year, because it had already delayed the game a couple of times and didn't want to again. It wanted this latest delay to be the last one, the delay that would see the studio go dark for two years before re-emerging with something concrete: what we now know is a promised 2018 launch.

"When we sat down to talk about it, the biggest risk we saw was telling people it was going to come out and then delaying it again, and saying, oh, you know, we said it was going to come out this time but we need another six months, and then after that six months being like, actually we need another six months," Vella says.

"There are only so many times you can do that before people tell you you're crap and that's the end of any potential relationship you have with them as players.

"It was like, we know we need some time, we think we know approximately how long that is, but instead of saying approximately how long it is, let's just say we're going dark and we'll come back when we believe we're ready. It was the most honest way of putting it. The least PR'd way of saying we're delaying is saying we're delaying for maybe a long time."

Some thought Below secretly cancelled. I wondered whether it had been - or would likely be - myself.

"A lot of people took it like we were cancelling the game, and I totally understand that," Vella reveals. "But in our gut it was just better to do that than to risk anything else and to let people down and have them become apathetic about the game. I would rather people be angry about it - or even worried it's delayed - than have them just be like, meh, I don't care about these guys any more."

Since that announcement, Capy has worked to get Below where it feels it needs it to be. It has spent months refining systems, adding content, cutting content, putting content back, and taking more content away. Vella mentions the old adage: the last 20 per cent of any video game development takes 80 per cent of the time, and says it's "never been more true than on this project". Below, he says, is a long game, fuelled by procedurally-generated content but also Capy-created bits and bobs, "hand-done" content for players to find. Then there's all of the various systems, all of the enemies, and all of the "moments" Capy wants players to experience.

"All of that stuff required either a bunch of polish or redo it from scratch because we weren't happy with the way it was," Vella says. "Even just taking the pieces that were mostly complete and giving them a hard look to see if they were actually going in the right direction.

"It's been a lot of work and taking the things we think are working and try to make them work even better, which is in a lot of ways just as hard as starting stuff from scratch."

Digging into the detail, Vella says Capy has done four full iterations, "almost from scratch", on the procedural generation system and how it builds the single screen levels of the depths of Below. Each iteration worked, Vella says, but there was something about each that didn't. Either it didn't feel like it was creating enough "gameplay moments", or it felt "too grid-based" and as a result "looked kind of janky", which was a problem because Capy wanted Below to feel like it was set in natural spaces.

Then there was the technical challenge of getting Below running well. The game has a unique, heavily stylised art style, but even more unique is the camera perspective, which is zoomed out and at times presents the player character as a tiny warrior on-screen. The single screen levels can be vast, despite being single screen. When you begin the game, you find yourself exploring a huge field of grass in a storm, with rain and wind battering each of the thousands of blades you can deform by simply running about.

Because of its aesthetic, Below doesn't look like the most performance-heavy video game, but Vella says there's plenty going on under the hood to tax the Xbox One, the console it's launching on first.

"We're so used to everything in games being up close," Vella says. "How close can we put the camera to a character? We want to be able to see their ear hairs if they're in third-person, or we want to be able to see the scratches on their guns if it's an FPS. For us to go the opposite direction, quite often people think that's easier to do. Of course they're going to do 4K / 60 frames per second, that's easy! But we're doing so much to make that work and it is actually extremely technically challenging to do so."

Capy originally intended for Below to run at a 1080p resolution and at 30 frames per second. But over the course of the development, and to make the most of the Xbox One X, it spent time boosting the game's performance to 4K and 60fps. This is made easier on the more powerful Xbox One X, but Below will run at 1080p and 60fps on the bog standard Xbox One, which Vella says was a challenge.

Below's aesthetic also evolved as the scope of the game ebbed and flowed. Early in development, Below was a lot brighter than it is now. Over the years, the developers have become more confident in making Below a game about the contrast between light and dark, about the mysterious lantern you find, about the way the fire pits and torch pillars work. Capy has become confident enough to shroud Below in actual darkness, to the point where you sometimes find yourself in what looks like an entirely black screen, save a small circle of light around your tiny warrior in the corner somewhere. "Even in the past little while - and by that I mean since we've gone dark - that's become more foundational for us," Vella reveals. "To be confident enough to make a game that is dark and hope to god people set their gamma settings correctly."

Burnout is one of the biggest issues affecting video game developers today. Developers, who work so hard for so long on projects, some of which never see the light of day, can sometimes exit the industry altogether, so exasperated and exhausted are they with the seemingly never-ending games they have become embroiled with. When you spend years working on a game that struggles for direction, or vision, or identity, developers can, understandably, lose faith. They can lose hope.

"We constantly have that balance between burnout and optimism," Vella says when I ask about how Below's development has affected the team.

"That's just something every game has, but the longer it goes, the more aware you are of it. It's definitely been a challenge. For me it's a little bit less so because I'm not into in the nitty gritty of the project. I'm not making assets or trying to solve some of the big ticket problems. But for the people who have been working on the game every day for years and years of their life, I know for sure it's been a very big challenge. The fact we're positive we can overcome that challenge together is one of the things I'm most proud of about the studio."

I ask Vella if he ever considered cancelling Below. His answer is unequivocal.

"No, absolutely not. It probably crossed the minds of other people on the team. But the idea of letting our team's work not see the light of day was never really an option for us. Everybody's worked so hard and put so much of their life and effort and creativity into the game, people need to see it.

"I'm 100 per cent sure there are people who are not going to like this game, but at least we know that going in, because of the type of game we're making. It's a hard game. It's a game that doesn't do the things some people like about games. Some people like having their hands held. Some people find constant death frustrating. That's okay. Some people aren't super into playing as a tiny little character. That's okay, too. At the end of the day, we put such good work into the game, I think, I never once thought we shouldn't keep working on it."

Like Below's tiny warrior emerging from the depths, for the developers of the game there is, finally, half a decade later, light at the end of the tunnel. Clearly, Below's development has had its ups and downs. In the game, when you die you respawn but must find your corpse to reclaim lost items. But the world is reshaped, the caves shifted slightly, the paths moulded anew, the procedural generation system doing its thing.

As I learn more about the depths Capy went to in the making of Below, I wonder if this is art imitating life. As Below repeatedly reshapes itself for the player after each death, the developers have reshaped Below - thankfully without death.

"It's happening, man!" Vella declares. "It's happening."