What the UK can learn from the Far East's battle with loot boxes

Laying down the law.

The debate surrounding loot boxes and in-game gambling has reached new levels, with the UK government now being called upon to change current legislation.

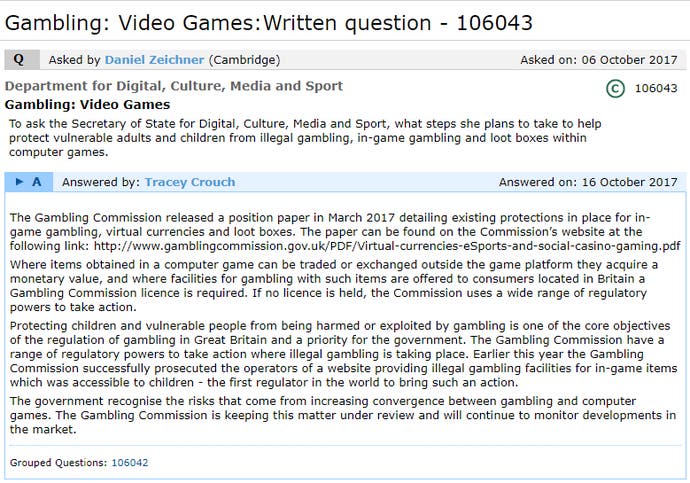

A petition calling for the government to adapt current gambling laws to loot boxes in video games surpassed the 10,000 signatures needed to trigger a response from government - a response yet to be issued. And an MP submitted questions to the Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport asking whether the government plans to enhance protections against illegal and in-game gambling and loot boxes, receiving an evasive answer.

The government is dancing around the issue of loot boxes. But it turns out some countries have already had a stab at regulating them - with varied results. Japanese Gacha machines are the seed from which western loot boxes have grown. Gashapons, or Gacha for short, are vending machines which dispense capsule toys when a coin is inserted. The Gacha system began to make its way into Japanese free-to-play mobile games in 2011, essentially as a monetisation mechanic, and it worked. Puzzle & Dragons became the first mobile game to net over $1bn using the system, but it quickly became clear there was a problem with Gacha - it was basically gambling.

Kompu Gacha games offered a grand-prize for players who completed a collection of specific items. This encouraged players to spend more on randomised gacha draws, but with a low probability of ever getting the items they needed (sound familiar?). The system soon came under fire for encouraging gambling, particularly in children, and Kompu Gacha was made illegal by Japan's Consumer Affairs Agency in May 2012.

In the wake of this, major mobile games developers GREE and DeNA (both of which saw share prices freefall as a result of the law) set up their own trade body, Japan Social Game Association, in the hope self-regulation would head-off government regulation. The trade body encouraged companies to publish their probability ratios, striving to regulate and control Japan's social gaming industry. This may sound like a great option for the UK and Europe, but companies still found a way to use Gacha mechanics and the body dissolved in 2015.

Despite the Kompu Gacha ban and the threat of regulation, Japanese developers still make money hand over fist with loot boxes and Gacha. In other words, some forms of Gacha and loot boxes are still legal and players are still spending insane amounts of money on Japanese mobile games which use them.

After all this legislation, one player was still able to spend $6065 in one night on Cygames' Granblue Fantasy last year. As a result, Cygames apologised and refunded players, implementing its own self-regulation on all its social games, which capped the amount players could spend on Gacha mechanics. Could a cap on loot box spend be put on place in the UK?

If government does move to tackle loot boxes, it needs to ensure the legislation is airtight or developers will work around it, as seen in China.

Back in May it became law for publishers in China to "promptly publicly announce information about the name, property, content, quantity, and draw/forge probability of all virtual items and services". In other words, game publishers needed to tell players in China the probability to get certain virtual items. At the same time, the law also banned game publishers from directly selling "lottery tickets" such as loot boxes.

Again, companies found a way around this, with Blizzard China changing the way loot boxes are 'purchased' to bypass the law. In China, Overwatch players can not directly buy loot boxes, instead you purchase the in-game currency with real-life money (for roughly the same price) and get loot boxes as a 'gift'. This just reverses the original system, as currency tends to come in loot boxes anyway, but it was completely legal.

In 2015, South Korea's National Assembly proposed changes to the country's existing game industry regulation. The amendments would require game companies release "information on the type, composition ratio, and acquisition probability" of items obtained by loot boxes. However, the proposition did not pass. The South Korean game industry, sensing the worst was coming, tried to self-regulate, but the government still feels not enough is being done and continues to push for statutory regulation. If the UK game industry smells trouble brewing, it may have a go at self-regulation in a bid to stave off regulation.

As previously mentioned, Labour MP Daniel Zeichner put questions to the UK government about loot boxes at the start of October. The response from government was predictably non-committal, answering both questions asked with the same answer which failed to address the issue properly.

Unsatisfied with the response, Zeichner is now following up his questions with another: "To ask the Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, pursuant to the Answer of 16 October 2017 to Question 106042, what discussions she has had with Cabinet colleagues on adopting protections against illegal and in-game gambling and loot boxes, such as those present in the Isle of Man, in the UK."

"It's clearly an issue that needs exploring," Zeichner tells Eurogamer. "I asked the written parliamentary questions to try and work out what the Government's provisions for player protection are in this area. We need to make sure that these kind of developments in gaming and technology don't just pass the Government by."

The UK may end up following the example set by The Isle of Man, which employs a tough stance on loot boxes. Tony Jones, e-gaming chief at the Isle of Man Department of Economic Development, clarified for Eurogamer the law in layman's terms.

"Our Gambling Supervision Commission (GSC) considers an activity to be licensable if:

- There is an element of chance (which there may be in the case of loot boxes because it may be random which items are in the box. Other elements of chance could be re-spawn locations, wind speed and direction etc depending on type of game);

- There is a prize in money or money's worth (which there may be in the case of loot boxes, depending on the contents) and;

- The activity is performed on Isle of Man infrastructure.

"If these three scenarios are fulfilled then the GSC would consider it to be gambling and a company offering the activity from IOM infrastructure would require a gambling licence. Offering the activity from IOM infrastructure could include registering the players and hosting the game.

"Examples of the element of chance could include respawn locations, wind speed & direction (in eg. Angry Birds) or loot boxes."

The Isle of Man government seems more tuned-in to the issue of loot boxes and, well, video games in general than central government. It takes specific in-game examples and applies them to the broader definition of gambling. In essence, the Isle of Man reckons an in-game item has a real world value, but the Gambling Commission does not.

So what can the UK learn from other countries' attempts to lay down the law on loot boxes? Blizzard's tactics in China have taught us that developers will try to get around legislation, while the Japanese game industry's attempts at self-regulation shows that leaving game companies to sort themselves out won't necessarily work. Where does that leave us?

The Isle of Man shows us what a revised, up to date approach might look like should the Gambling Commission be prompted into action. But the obvious next question is, how would publishers react? How would game companies move to protect their profits should the government decide loot boxes are gambling, games that have them must carry gambling warnings and publishers must fork out for gambling licenses?

No doubt video game executives are praying we don't have to find out.