What is the point of Xbox One DRM?

Record and publishing industry studies suggest piracy and used sales may be red herrings.

Did you know that the new Xbox One operating system is so in love with multi-tasking that it will allow you to glue a pair of apps together on the dashboard so they always launch simultaneously? So, let's say that every time you want to play FIFA 14 you also want to phone your mum. Now you can!

At least, that's what I thought for a few seconds when I was reading the ad copy on the Xbox One website earlier. "Pin your favorites to your home screen," it says. "Best of all, jump between apps instantly, or snap them side by side to do two things at once." You can see where I went wrong - it's just talking about Snap mode, not dashboard glue - but you can also see how I misread it. (By being an idiot.)

Not that Xbox One needs my help being confusing. The biggest question mark remains over game ownership - specifically what rights we have to resell the games we buy. Microsoft has made it clear (in a fashion) that we're being sold licences, not games, and that you can log in on any Xbox One unit and access the games you've licensed. But it also claims to have a way for us to resell licences - in stores and/or online - that it will talk about later. Lucky us!

Some have suggested this licence-based approach is an attempt to stymie piracy, the implication being that less piracy will lead to more game sales. Others have noted that it might reduce the impact of used game sales on sales of new games. But surely gaming isn't the only medium facing these conditions? This week I thought I'd look up what happened to other artforms when they faced similar situations.

There's research in games too, of course. On Wednesday Wired reported on a new study citing Japanese video game sales that presented uncertain conclusions: on the one hand, it said the removal of a used market might lower profit-per-game for publishers by 10 per cent; on the other, it said that the lack of a used game market might lead to lower new-game prices because consumers would stop factoring in resale value. As Wired noted, however, these outcomes are extremely unlikely because in reality a used game market would have to be replaced by something else.

What about the world outside games, then? Well, in 2005 the New York Times trawled through various academic papers assessing the impact of the used book market on sales of new books. It suggested that the presence of a used book market makes consumers more willing to buy new books, that consumers often take resale value into account when buying new books, and that there are probably two distinct types of buyer - those who purchase only new books, and those who are quite happy to buy used books.

Those suggesting the licence approach is an attack on piracy, meanwhile, might be interested in what happened in the music industry. The paper a lot of people point to is The Effect of File Sharing on Record Sales: An Empirical Analysis, a peer-reviewed paper cited in the Pirate Bay trial. It says stuff like this: "We find that file sharing has only had a limited effect on record sales... This estimated effect is statistically indistinguishable from zero despite a narrow standard error."

In other words, used markets and piracy are complicated subjects and there's plenty of data that suggests they don't do as much harm as we're told. Sure, if you write a book or a piece of music and you're faced with a guy who downloaded it for free, you're going to hate that guy, but it's important to think bigger than just hitting that one guy in the face.

Games industry bosses know all this already, of course. They generally understand economics and also have business intelligence and analytics departments who constantly, hungrily devour all sorts of research. They will know very well - albeit in crude, artless terms - what drives and deflates sales of the products they have on the market, and while they may have a natural aversion to piracy and used sales similar to that of the artist who wants to punch the pirate or second-hand buyer in the chops, pragmatic execs will know that the situation is not black-and-white.

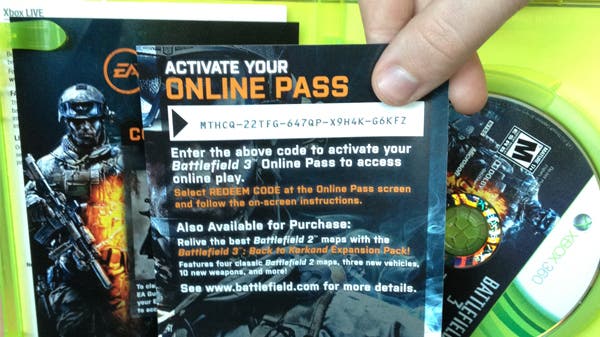

Want proof? Well, there's already some evidence that targeting used game consumers doesn't work and it's hiding in plain sight. EA's celebrated decision to kill the Online Pass may have sounded like a prelude to leaping into bed with Microsoft's new licence system once we heard about the latter, but listen to the way EA's John Reseburg explained the move: "We've listened to the feedback and decided to do away with it." That phrase - 'listened to the feedback' - is corporate code for 'counted the receipts'. In other words, Online Pass may simply have been retired because it didn't make money.

So, if not for the sake of preventing piracy or bringing the used game market to heel, then why make this decision to license games instead of letting people own copies of them that they can use any way they like? Sure, games all have to be installed to work, which would create the possibility that friends could rampantly share game discs for free, but that's another decision Microsoft controlled. It didn't have to insist on game installation. So why licences, then?

The worrying thing, when you look back at Microsoft's history of product support, is that this is a company that loves to build in obsolescence. Phil Harrison sort of denied this will be the case with Xbox One, telling me he was "pretty confident" I would still be able to play stuff like Quantum Break in 25 years' time. One reason for his confidence may be the way that the Xbox One operating systems work - the 'game' OS is a custom Virtual Machine that could be included in future Xbox hardware for faultless backwards-compatibility, in theory. But as I said to Harrison, things like Games for Windows don't give me the same confidence. (Take care of your XBLA library, eh?)

It will be interesting to see how Microsoft addresses this question in the weeks and months ahead. What kind of guarantees can it provide that our games will be safe for years to come? What happens if Microsoft just changes its strategy again and all of this becomes an inconvenient legacy distraction?

In the meantime, only one thing is certain: the move from ownership of a physical disc that works on bespoke hardware to licence-based control of all content is a fundamental change in how console games are going to be bought and sold. And I don't understand how it's possible to like it.