Video game poetry collection heads to Kickstarter

"Producing books that engage with pop culture is a much more radical idea than it should be."

Jon Stone and Kirsten Irving hope to spend £1500 of your money on Swedish Munken paper. Lovely, sensuous Swedish Munken... Wait, what is that exactly?

"One of our previous projects, Birdbook, contained a lot of black and white illustrations, and in the first proofs we got the paper was too thin - the images showed through," explains Stone, who together with Irving runs the micro-publisher Sidekick books. "We looked around for a printer that had access to a thicker paper, but one that was still clearly book paper - natural off-white, not glossy. One printer said they could do it but they had to source it from Sweden. We didn't question it." He laughs. "Turns out it's rather luxuriant stuff."

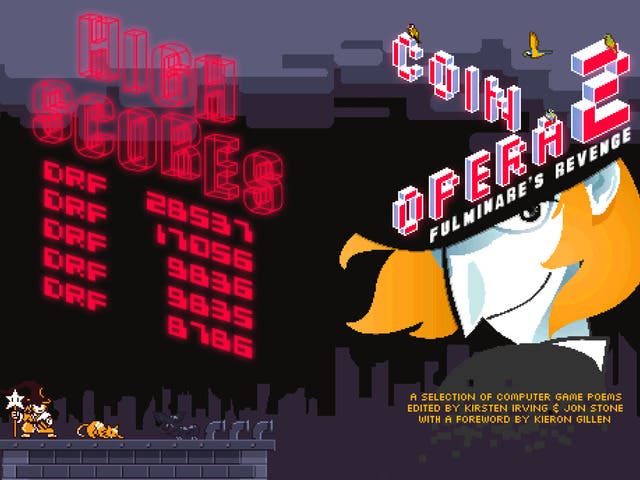

The paper's needed for the duo's second anthology of video game poetry, Coin Opera 2, which has recently headed to Kickstarter. The cost of printing a first-run comes in at £3000; Sidekick aims to crowdsource half of that, and fund the rest internally. There's currently 12 days left on the campaign clock.

Coin Opera 2 promises to be a fascinating collection. Featuring work from poets like Chrissy Williams, Ross Sutherland and Abigail Parry, it covers everything from popular franchises to classics and "even the odd browser game". The whole thing's part of a wider attempt to explore similarities between poetry and video games. "Coin Opera, the first book, came about not long after we made Bard Games, a bonus booklet with our magazine Fuselit," says Irving. "Bard Games took tabletop games and applied their rules to poetry. We did Jenga, Cluedo, Old Maid. To give you a rough idea, Dominoes, which was probably the most successful form in the booklet, was a two-player game, in which each player wrote a two-line stanza, followed by their opponent mimicking the sound of the second line in their first line."

"It was another book, Critical Play: Radical Game Design by Mary Flanagan, that started me thinking about the similarities between how games and poems are made and the way in which they function," adds Stone. "She writes a lot about the history of gaming - as in pre-computer gaming - and ties it into the work of the surrealists, some of whom were also poets. I realised how absolutely crucial this concept of play is in human development, in how we form and test ideas about ourselves, and that's something that's key to my interest in both poetry and gaming. It's not as obvious in poetry, but it's there, particularly towards the surrealist and experimental end. I talk a little in the introduction to Coin Opera 2 about the idea of 'playing' a poem as a reader, which in some ways is similar to how one explores a virtual world, testing its limits and the way it reacts.

"Then there are these other comparison points - how repetition works, how rhythm, tone and pace is essential to the character of a game or poem, and of course, economy of language. Both poems and games are often about doing much with little, making every last thing count.

"The poetry world feels oddly closed off," concludes Stone, "and producing books that straight away, on their face, engage with contemporary pop culture is a much more radical idea than it should be. In a way, gaming culture feels a little like an island too - albeit a massive, densely populated one - and somewhere behind both these books is this frustration I feel that there isn't more communication across the arts, across different sub-cultures. I'd like to see more gamers who know their poetry and poetry readers who know their games. I have this idealistic idea about the Coin Opera books kicking that off."