The Swindle: Dan Marshall's brilliant new cat-burgling platform game

And how it was saved from cancellation.

Last Tuesday, in a quiet part of Dorset, 'action hero' became a verb. Come to think of it, can a phrase really be a verb? Whatever. To action hero, as in: "I action heroed in through the skylight and then the cops arrived and I sat on a landmine. Kaboom." Quite a lot of anecdotes from last Tuesday begin with "I action heroed in...." Quite a lot of them end with "Kaboom."

To action hero (verb) is possible because of Action Hero (noun), an upgrade in Dan Marshall's latest game, The Swindle. Action Hero "does absolutely nothing" and is also "totally essential," according to Marshall, who is probably best known - outside of his family, I suppose - for the Ben and Dan adventure games. The Swindle is a bit of a departure: a procedural platformer about cat burglary, a steampunk stealth game made by a man who admits that he doesn't really like stealth games.

Definitions will only get you so far with this one, however, just as references will only get you so far (Spelunky meets XCOM is my personal favourite). No matter: I've played The Swindle and it's got the makings of a real dazzler. Action Hero's a dazzler too: a perk that allows you to smash through windows and doors in glorious sugar-glass slow motion. It does absolutely nothing. It's totally essential.

The first thing I ever heard about The Swindle was that it had just been cancelled. This was around a year ago, and the reason given was laudably direct: it wasn't much fun to play. "I'd been working on the game for a while, and it was a great idea," says Marshall, who puts a painful stress on that last word. "I loved the central concept, which was breaking into houses and then breaking out and then breaking back in later to rob them all over again."

There was a problem, though - two if you counted the tricky AI needed to chase a player through an entire level as Marshall desired. The hook for The Swindle came down to an AI game director who would beef up security in between your robberies, based on the choices you'd made along the way. If you went in through the sewers, he'd add security cameras down there. If you came in via the roof, he'd put a few extra patrols in the attic. "In truth, you just never went in the same way twice," laughs Marshall. The whole game was built around a long con, and the long con didn't work. "There comes a certain point where you just have to down tools."

Or rather, there comes a certain point where you just have to down tools and spend a few months playing Spelunky.

It was not exactly love at first sight, however. Marshall's early concerns about Derek Yu's procedural masterpiece are pretty easy to understand: he didn't like games in which the main character's nose is a different colour to the rest of the main character's face. "I think it goes back to an old cartoon from the 1980s," he muses. "David the Gnome?" (Hmmmm.) "But then I picked the game up on Vita and just fell in love with it. I saw in it what everyone else saw in it: this beautiful game where all these little systems are working together."

What struck Marshall the most was some of the basic choices Yu had made. "I was playing it and I thought: this has all the things that The Swindle needed in order for it to be good. With the new version of the Swindle, the concept is the same as in the old version. The gameplay is surprisingly similar. But it's got the procedurally generated levels which Spelunky did, and that's better than constantly going back to the same place. Also, the enemies are predictable now. They're moving left and right, they have a certain set pattern. Basically: my game would work better if the levels were procedural and the guards were stupid."

He's right. Playing the current build of The Swindle reveals a game that cobbles cramped, labyrinthine environments together with tooled-up patrolling idiots to brilliant effect. It's a game that encourages you to make a plan, and then throws the unexpected at you with eager force so you constantly have to alter that plan as you dash around, grabbing as much cash as you can before the guards cave your head in.

Money bags litter the floor and computer terminals offer a one-shot payout if you have the time to hack them. Everywhere you look is a wealth of rickety 19th century impedimenta: steampunk hardware juddering like defective cappuccino makers, robo-bobbies roll to and fro on squeaky wheels. Slummish whimsy meets chaos, and the result is beautiful: Shanty, the game's first district, is a place where flophouses and crumbling tenements are stacked improbably high and teetering on top of one another. Beyond it, Warehouse is austere and nearly still, aged wood creaking and tarnished metal gleaming beneath cold blue moonlight. This is a great world to burgle.

Although Spelunky's a key influence, The Swindle never feels like anything but The Swindle. It's a stealth game, for starters, and you realise just how distinct a stealth game it is once you trigger an alarm. On my first, deeply tragic runthrough last week, I turned up in Shanty in the copper-plated shoes of Theodosia Robinson. I proceeded with a quiet caution, sticking to the shadows, staying up high, dropping down chimneys to collect loot when the guards were elsewhere, and then wall-jumping back into the warm darkness. This worked fine until I pulled off a tricky move to miss some floor spikes, and stumbled right into the path of a roving security drone.

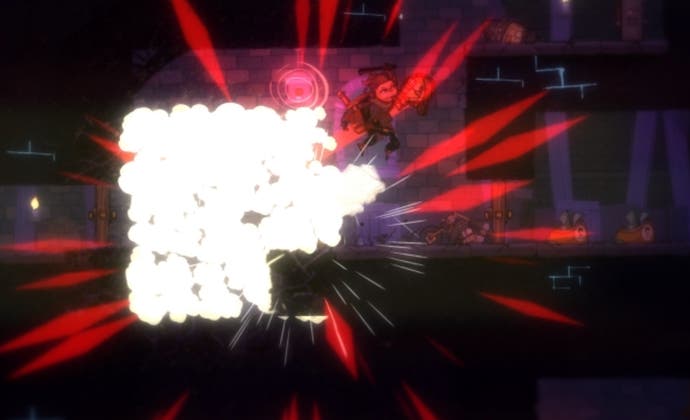

Suddenly, everything changed. Alarms went off, the music shifted from Sauntering Organ Grinder to Organ Grinder's Accidentally Electrocuted Monkey, and worst of all the guards started to pick up the money bags as the computers started to drain cash. No, that wasn't the worst, actually - the worst is that, after a short period, the cops turned up, one of them drilling right through a wall with a pneumatic pogo stick, and putting a size 12 boot through my wishbone.

This is the rhythm of The Swindle, the shift from a measured world of wall-slides and stealth takedowns to a kind of headlong flailing dash, cash spewing everywhere and robots popping out of closets. Crucially, once you've got enough experience, you'll realise that this rhythm is yours to control. Everything is: you choose how to go about your burglary and what to prioritise, and you even choose when to leave - as long as you can get back to your evacuation point, a ramshackle drop pod that takes you back to your zeppelin HQ, which clanks through the toxic yellow skies above. Every heist is a one-off that you'll never see again. Every death wipes your haul-boosting multiplier and chucks you back into the game as a new thief with a new procedurally generated appearance and scrambled chunk of brassy Victoriana for a name: Zachariah Deathcrow, Ginny Bogwort-Headcracker, Missouri Deadeye-Tealeaf. These are names to cleave tightly to as you dance through laser grids and pick a drafty mansion clean, as you action hero through a window, as you scarper.

So few games can do justice to the sly, panicky promise of thievery, and a lot of the magic in The Swindle's case comes down to what Marshall refers to as the arms race. The arms race is about is giving a game the tools and the inclination to fight back against the player - to keep in step with the kind of madness they can unleash. It's about loading a game with checks and balances, but tilting them so they feel like dangerous opportunities. Take machine gun drones. You can hack them if you have the time and the upgrades, and then they will switch from enemy to friend, zipping through the level and picking off targets. Once they're out of shots, though, they'll briskly explode, possibly taking you with them.

The arms race leads the way into the longer-term game, where abilities and tools can be bought and tricked out. It's a dangerous notion, adding persistent improvements to such arcadey action, but Marshall's enthusiasm is palpable as he picks his way through the shop, explaining his favourites. Double jumps, quad jumps, Action Hero, bombs, remote detonators, the ability to stay still while attached to a wall: these aren't incremental improvements to basic abilities as much as they're a broadening of possible approaches.

"I like the feeling that I'm building something up," says Marshall. "Spelunky always pretty much sets you back to square one, but Assassin's Creed 2 really did it for me. Assassin's Creed 2 had the perfect economy: constantly showing you things and going, 'Look at this nice gown. It's 10,000 euros!' And you go, 'Aw, I've only got 500 euros. I'm saving up for that gown!' That's why you go round pickpocketing people. Every 9 quid counts in Assassin's Creed 2. That's where this came from. I love seeing your bank account go up - and go past the number you have in your head."

Beyond that, is a fiction of sorts, although it's very loose and Marshall admits he may cut it entirely. "I didn't want to put a plot on it because I don't think it's that game," he says. "But I think you need a motivation because I think you need a final swindle - a last level. And so the idea I'm toying with is that Bow Street are about to plug in an artificial intelligence that will survey every inch of London. If this thing gets plugged in, you and all other thieves will be out of a job. So the idea is that you're going to steal it before they can turn it on."

Topical! It's another embodiment of the arms race. "I realised there was a slight flaw in the game design," says Marshall. "Because you choose when to leave the level, there's nothing stopping you from running in, stealing £800 and then running out again.

"With Bow Street and its AI, the idea is that each level is now a day, and when you start, you have 100 days remaining. 100 days before they turn it on. You have 100 days to mess around with, and I think you'll need 50 of them just to learn not to kill yourself every time you turn a corridor." Marshall laughs. "The idea is that once it starts to get fraught - eight days, five days, two days - you can buy a hacker that is a direct link to Bow Street and will disrupt the AI countdown. You can basically buy extra time. It's kind of beautiful because you suddenly find yourself with this gut-wrenching choice. The ideal for me is that you're in a building and it's one day before the singularity comes on, and you realise that you need another three grand to buy another three days. It's got that sort of XCOM thing, kind of against the clock."

This is one of many ideas Marshall's still turning over each day as he loads up The Swindle and starts to tinker with the world he's created. It sounds like the most exciting way to make a game, like Marshall's a strange kind of steampunk scientist toying with a biomechanical trainset that's gotten really out of hand.

As I leave, he's agonising over something called the Auto Steam Purge, and this drives home just how deep he is inside the game's systems, and just how much he has to think about the possible outputs of every single input. "Urgh," he says - and he actually says "urgh" - "the Auto Steam Purge is controversial. It's a one-hit kill world, and that's made things so exciting, but the Auto Steam Purge means that the first time you're spotted you give off a massive cloud of steam so you might not get hit. It's nice, like a second chance."

So who is it controversial with?

"Me!" he laughs. "It's one of those things that is good to have and when it kicks in you really appreciate it, but it does remove a little of the purity of the gameplay."

He pauses for a second. "I think if I just make it really expensive it will be fine."