Comparing the stunning space vistas of Elite: Dangerous, No Man's Sky and Space Engine to NASA images

Found in space.

He has seen things you wouldn't believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. C-beams glittering in the dark near the Tannhäuser gate. Roy Batty's dying monologue is a key scene of Ridley Scott's Blade Runner, its pathos buttressed by a sense of wonder in the face of things no ordinary human being will ever see.

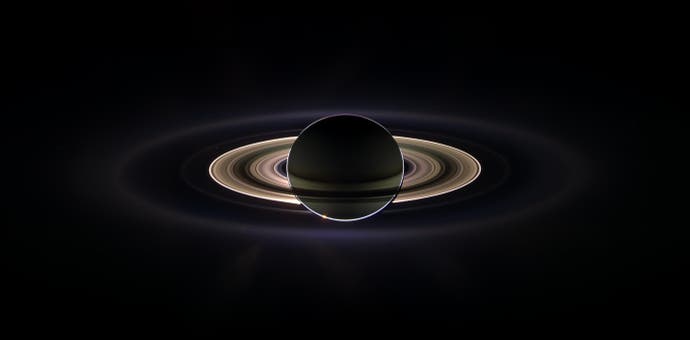

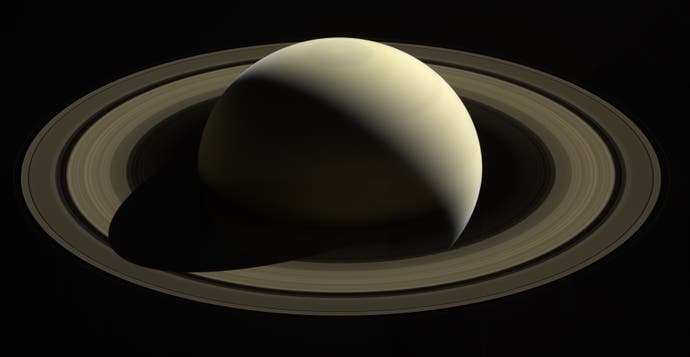

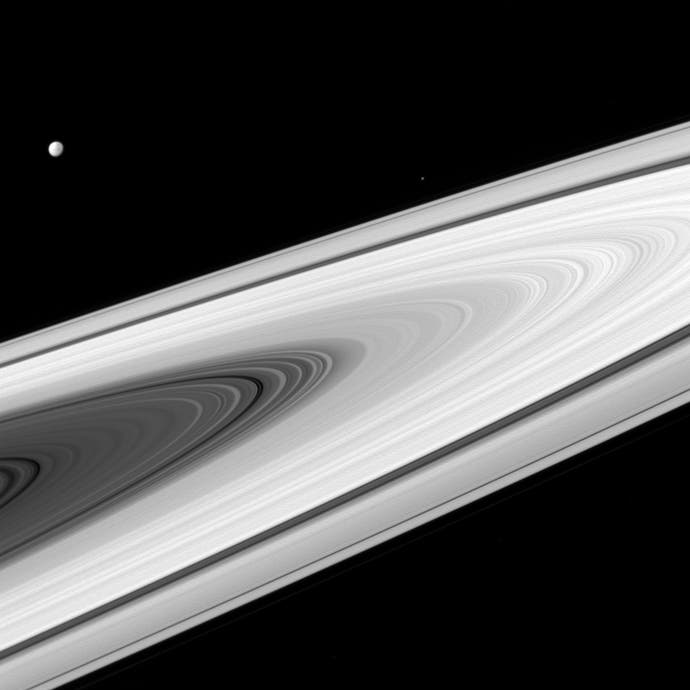

As I'm writing this, the Cassini space probe, which left Earth in 1997 and arrived at Saturn and its moon in 2004, is about to end its mission by plunging into Saturn's atmosphere. Unlike Batty's experiences, what Cassini 'saw' about 1.2 billion kilometres away from Earth will not be lost like "tears in the rain". Despite their beauty, the images captured by probes such as Cassini are small consolation for those of us who fantasise about visiting other planets. Roy Batty's last words and Cassini's images tickle the imagination and create an itch that is impossible to scratch, a longing for out-of-reach places. It doesn't help that what humanity has explored so far of the universe, even with the help of robot eyes, is a fraction of a drop in the cosmic ocean.

Thanks to an inundation of sci-fi stories, the fantasy of space travel is more relatable than it has any right to be, and no medium is better suited to indulge that fantasy than games and simulated worlds. Computers have always been adept at simulating basic physics, and modern graphics and the procedural generation used to create near-infinite worlds has come along far enough to create planets with striking geological features and landscapes.

There are many ways to explore space from the comfort of your chair, and I'll take a closer look at three of them. Elite: Dangerous and No Man's Sky hardly need any introduction. Space Engine, a breath-taking (and free) simulation of our entire universe, isn't really a game at all, but perhaps the best choice for the would-be explorer with access to a decent PC; what game lets you explore literally billions of galaxies?

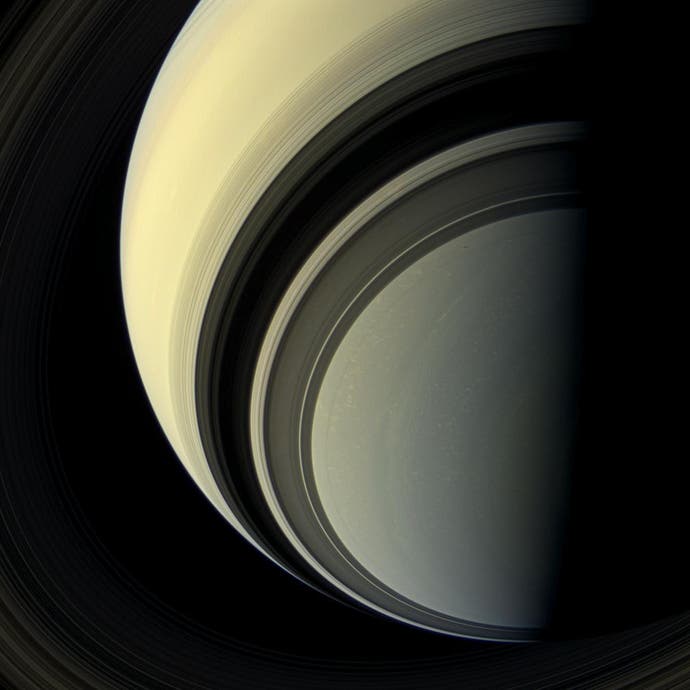

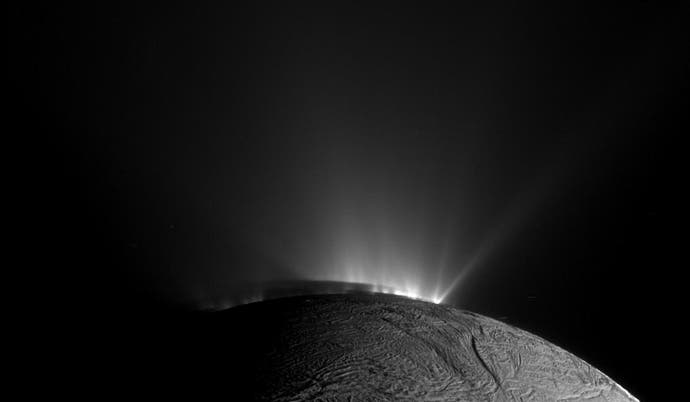

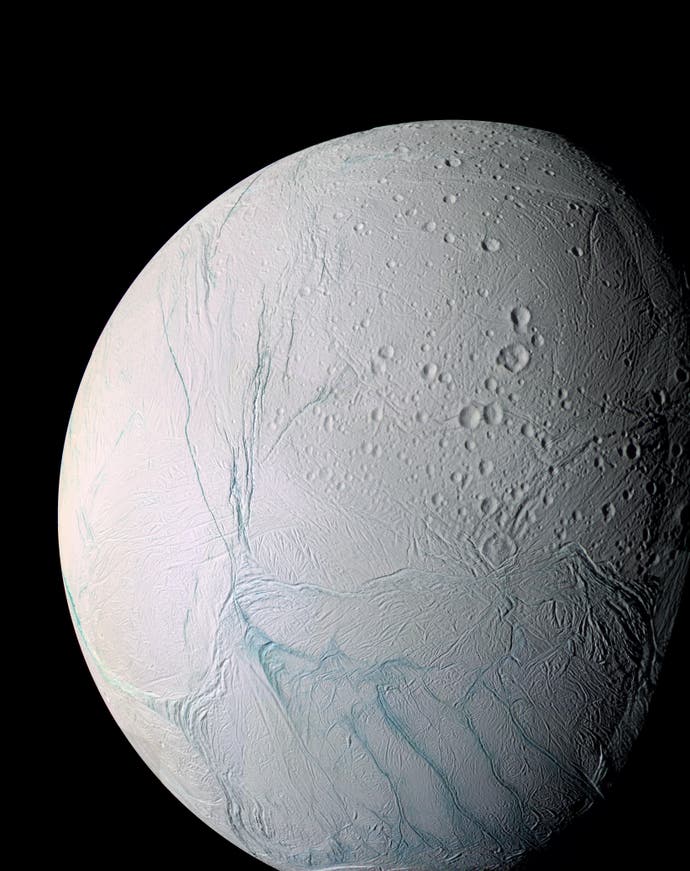

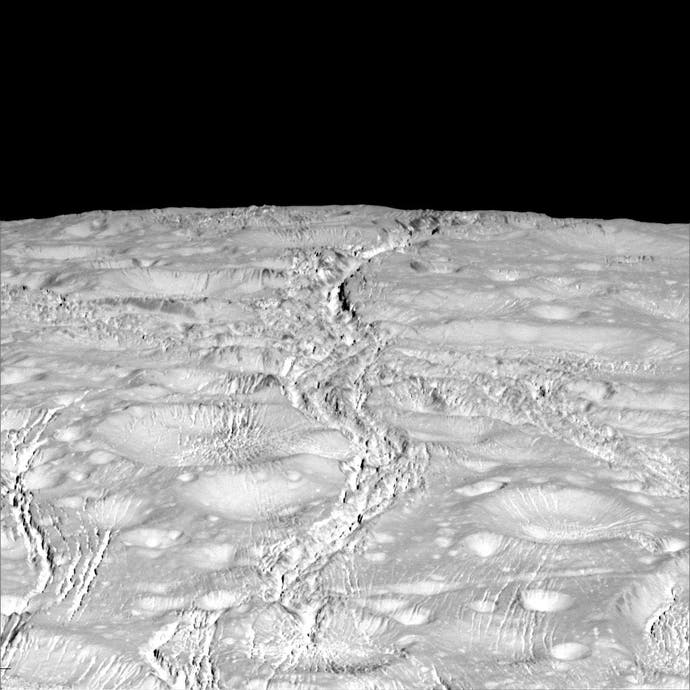

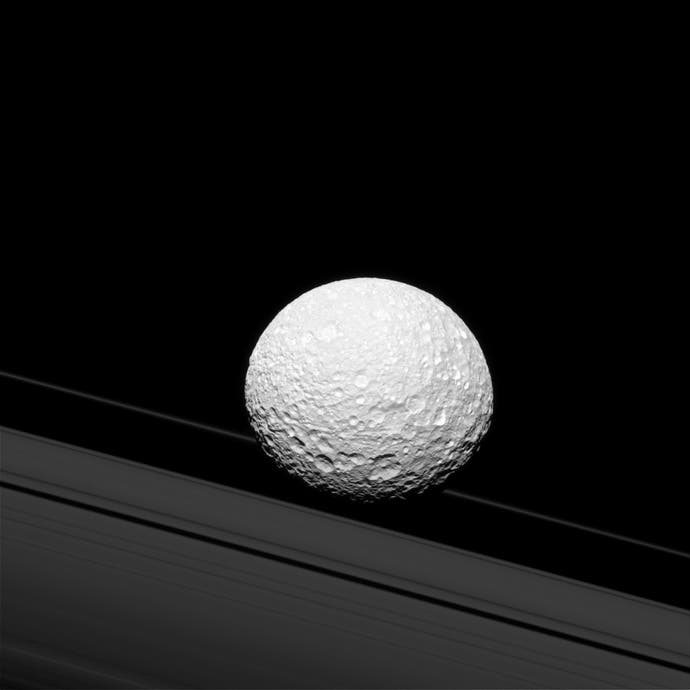

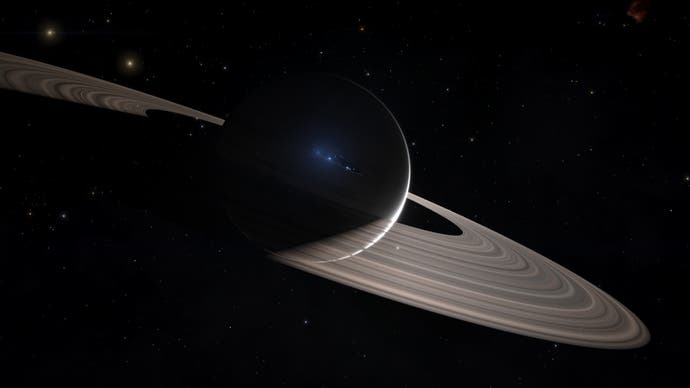

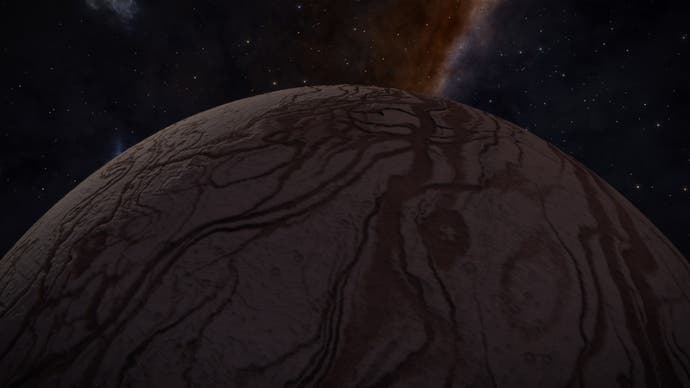

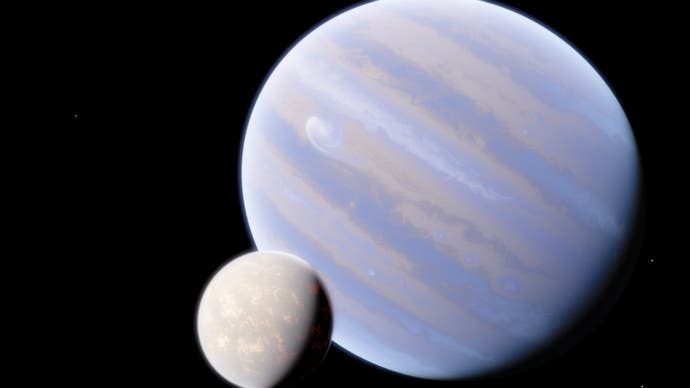

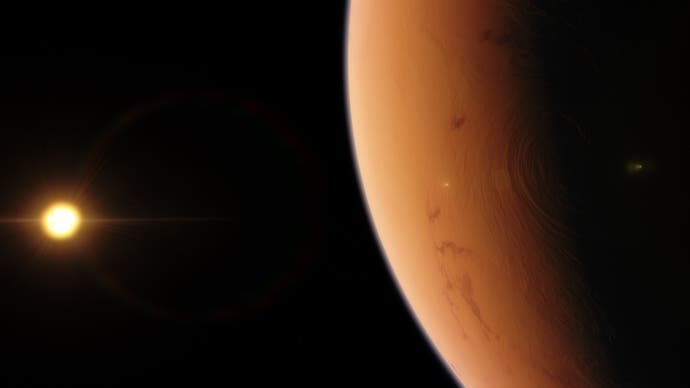

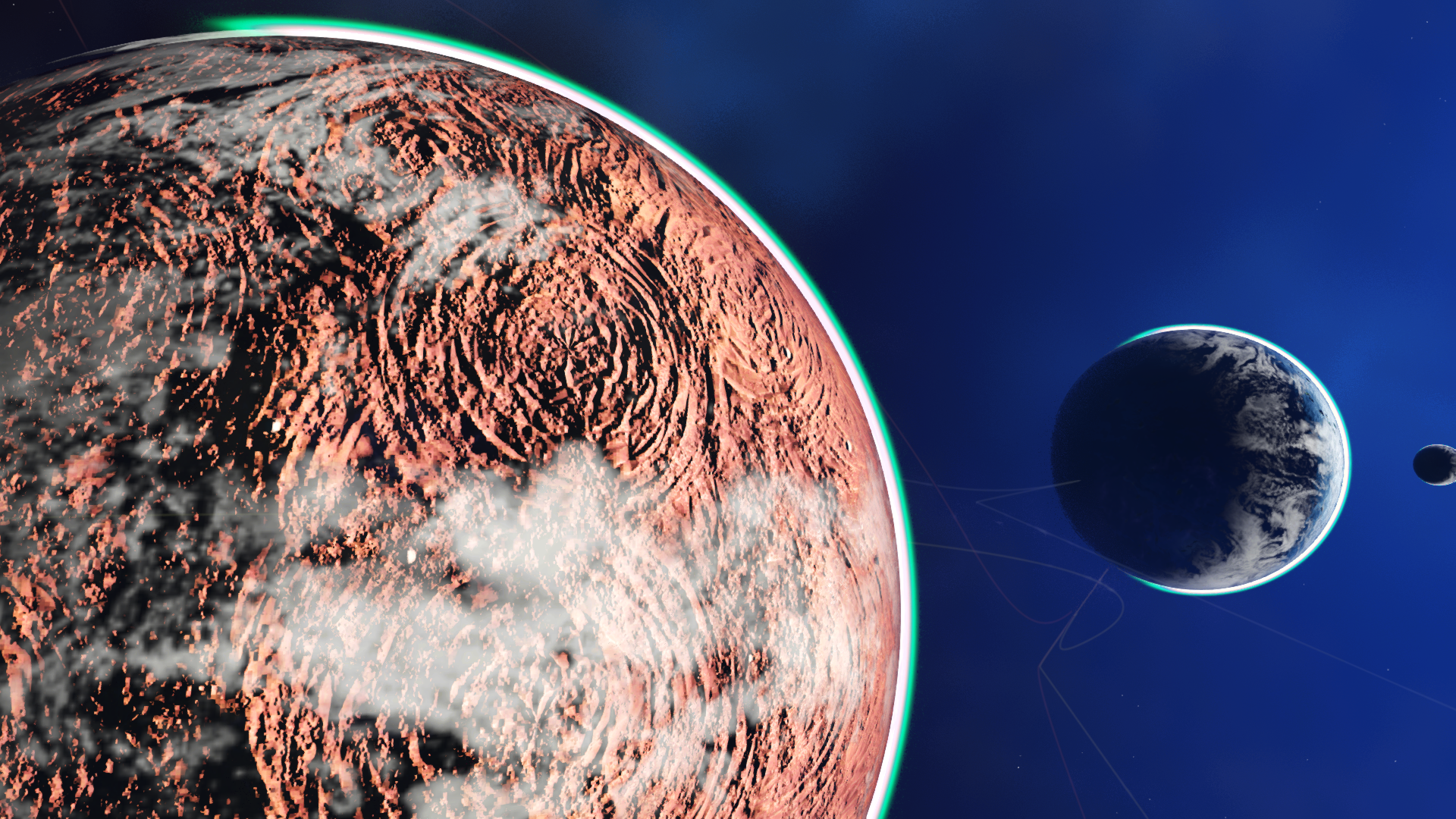

Planets and moons are of course the favourite destinations of space explorers, both real and virtual. Suspended before you in the void, they present a sight not unlike those from actual space photography, some familiar from our own solar system, others more speculative or even wholly fantastical. Storm-covered gas giants, barren wastelands pockmarked by thousands of meteor impacts, ice worlds with surfaces twisted into unique patterns... We know the faces of such planets from Cassini's forays: Saturn with its colossal ring system, and its moons like crater-covered Tethys or icy Enceladus with its geysers and underground oceans which are considered the likeliest place for alien (microbial) life in our solar system.

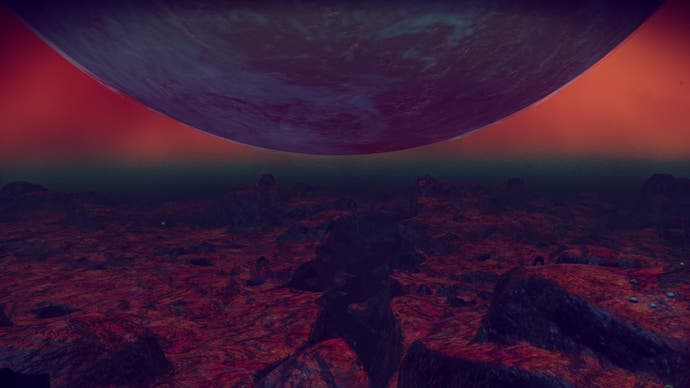

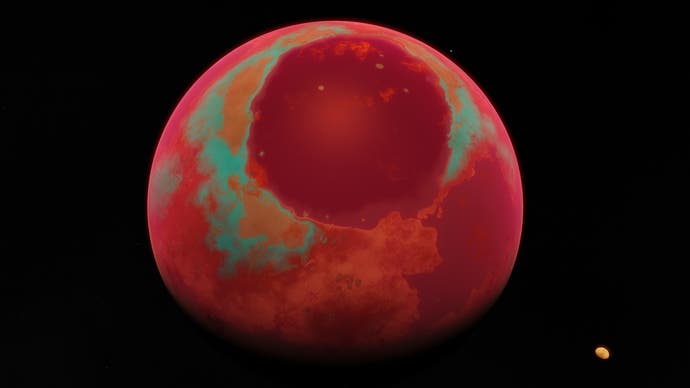

Elite: Dangerous as well as Space Engine let us explore our immediate galactic neighbourhood, but in many ways, their most fascinating discoveries begin where our knowledge becomes fragmentary and procedural generation kicks in to fill in the gaps. Space Engine especially offers some spectacular planetary encounters, from ocean planets to garish red-green 'frozen titans'. No Man's Sky, unburdened by aspirations of scientific accuracy, takes a more fantastical and artistic turn with strange colours and outlandish geological structures.

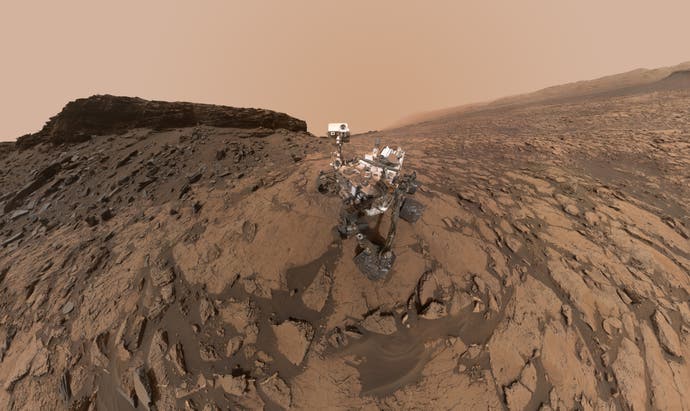

The ability to land on these objects is one of the advantages these games have over reality. Real images of alien landscapes - as opposed to images taken from orbit far above the surface - are quite rare. Apart from our own moon, we are only familiar with the Martian horizon from the Curiosity and Viking rovers. The Russians were able to take some pictures of Venus' surface in the 70s and 80s. The Huygens probe - carried by Cassini - recorded its landing on Saturn's moon Titan - whose liquid methane and ethane oceans are another potential habitat for alien life.

No Man's Sky capitalises on our unfamiliarity with the landscapes of other planets by churning out some truly alien vistas of monoliths beneath golden clouds, twisted, tubular rock "growths" and gravity-defying islands floating in the sky. In a way, however, it's a comfortable alienness with flora and fauna on practically every planet. Space Engine can't quite match the visual variety of No Man's Sky, but what it lacks in this department it makes up for in authenticity. Zooming ever closer into the amazingly detailed planetary surfaces and getting a beautiful impression of what a sunrise on another world might look like is an exceptional experience and a true feast for the discriminating crater connoisseur.

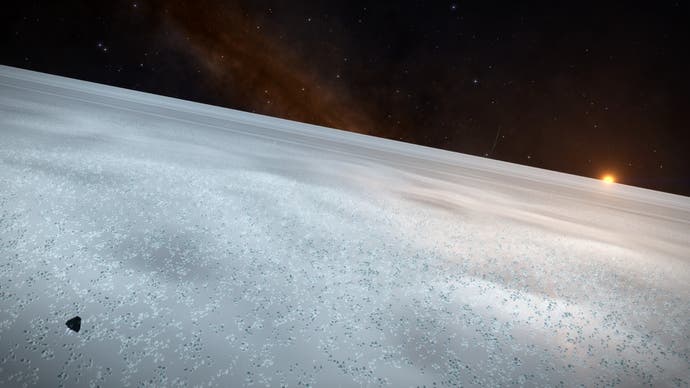

Unfortunately, Elite: Dangerous doesn't allow us to land on planets with an atmosphere, but its vacuum-girdled wastelands have their own magic. Spotting a gigantic crater from space, seamlessly approaching and landing next to it to explore it with your SRV (Surface Recon Vehicle) has a certain gravitational pull even if it offers no real benefits to the player. Realistically, the absence of any atmosphere makes it incredibly difficult to judge distances - as the Apollo astronauts landing on the moon, too, realised. The scales are hard to comprehend. Landing right next to a crater for what seems like a short excursion, it can easily take your high-speed SRV twenty minutes merely to drive down the slope to reach the outermost edge of the enormous crater floor. Getting lost in a ring system is a similar experience - a pretty piece of jewellery from a great distance, an ocean whose limits are barely discernible from up close.

As you flit past whole star systems in just a matter of seconds in Space Engine, planets and even stars may seem incredibly small and insignificant, but no game could ever hope to give a similarly dizzying impression of the immensity of our universe. Zooming out farther and farther until the Milky Way, at first barely contained by the screen, slowly shrinks down to a tiny star-like dot among a pattern of thousands of other galaxies and realising just how much empty space the cosmos consists of is a disorienting and queasy exercise in existential dread. The quasi-infinity of No Man's Sky seems cosy by contrast. It lacks the disconcerting, cold emptiness of Space Engine or Elite, instead presenting a universe of plenty, full of life, warm colours and distractions.

Despite their differences, there's one thing Elite, Space Engine and No Man's Sky all have in common: the stunning ways in which procedural generation, physics simulations and your own point of view often collide to create fleeting moments that leave you no choice but to frantically punch that screenshot button. A double sunrise in a binary star system (as in Star Wars' Tatooine), colossal shadows thrown on a planet's surface by its own ring system, or a gas giant looming over the tiny moon you're standing on. A fleet of spaceships coming to a sudden halt next to an asteroid field, a strange alignment of planets, or simply a star's rays striking rock formations in just the right angle to create eerily beautiful lighting and shadows.

These moments depend on a confluence of variables and may be hard to replicate or come across a second time. Unlike the images sent to us by space probes, these unreal spectacles belong uniquely to the virtual explorer who discovered them on their own initiative and with their own eyes. They are perhaps the closest we're ever going to get to seeing attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion, or C-beams glittering in the dark near the Tannhäuser gate.

And they are video games at their very best.