The serene, interconnected world of the brilliant The Settlers 2

Veni, vidi, vici.

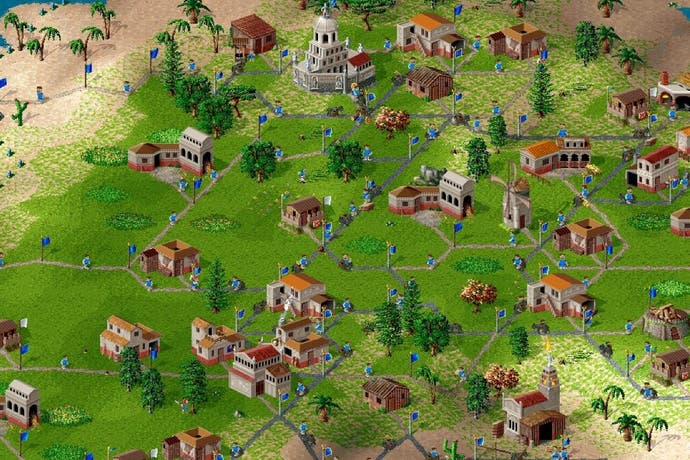

I find The Settlers 2 spellbinding. I could watch my tiny happy village dudes for hours as they march back and forth between checkpoints along roads, passing goods and raw materials up and down the chain. One moment they're transporting the flour and water sent off to the bakery to be made into bread to feed the miners who dig iron ore out of the ground for smelting into slabs that are combined with coal to forge tools and weapons. The next, they're hauling logs to the sawmill and ferrying pigs to the slaughterhouse so that they have boards and meat, respectively, for the builders and miners to do their jobs.

Everything in The Settlers 2 feeds into everything else in a remarkable economic simulation of village life, and you get to watch it all unfold before your eyes - all made reality by hundreds or thousands of nearly-identical little men in blue who exude personality in spite of their sameness. It could easily be tedious, especially with its pedestrian pace, but the game has soul.

Its many abstractions take on a life of their own. The simulation entrances as its agents entertain. And just as The Sims succeeded by inspiring players to find meaning in actions where there was none, The Settlers - this second entry especially - makes you feel as though that little dude with the cape is a masterful swordsman itching for a fight while this little dude loves his job but the other little dude - the chubby one assigned to a seldom-used patch of road - is bored stiff and would rather be chasing the cute rabbits that hop around the nearby grassland.

The Settlers 2 charms you in the small and quiet moments. The dogsbody "helper" villagers intermittently skip rope, wave at you, check their watch, throw snacks into their mouths, and read the newspaper while they wait for work to do. You can watch wildlife - or anything, really - through an observation window that has three zoom levels, three sizes, and both "follow" and "still" modes. It's handy for keeping tabs on what's happening at the other side of the map, sure, but I used it mostly to observe behaviour.

Ever wonder how computer pathfinding algorithms work? Watch enough builders wind their way along your network of roads en route to a construction project and you'll develop an intuition for it. Confused as to why certain tasks in your village are taking so long? Have a look for stress points in your transport network and keep an eye on where the relevant resources are going, then relay some roads or tweak the transport and distribution priorities. In an era when simulations tended to be opaque and imprecise, The Settlers 2 was exactingly transparent. It was an agent-based, small-scale city builder 17 years before the SimCity reboot made a hash of the idea.

Let me walk you through a couple of examples. You need soldiers to guard your borders and protect the interior of your mini-empire. To get soldiers you need swords and shields - one of each makes a private. Swords and shields are forged in the armoury from iron and coal. The coal comes straight from a mine (which itself requires food to feed the miners), while the iron comes from smelting iron ore and coal. It's important to note at this point that all buildings require raw materials for construction - boards processed from chopped wood, and perhaps also stone from a quarry or granite mine - as well as a builder, a road leading to them, and specialist workers to occupy them. (And each specialist requires specific tools forged by a metalworker, and so on down the rabbit hole.) But let's skip those complications and get back to the soldiers.

So you now have a sword, a shield, and an empty barracks or fortress or whatever other military building. At some point a spare helper stationed in your headquarters will be recruited, and he'll traverse your road network to the building in question. That expands your territory and lends you some basic protection against your encroaching rivals. But to be properly protected you'll need both more soldiers and higher-ranked ones, as well as alcohol-infused gallantry. Soldiers gain rank from oversized coins dropped off where they're stationed. Those coins are made in a mint from coal and gold. Beer, meanwhile, comes from wheat and water, and it gives the soldiers a little fighting boost when they get recruited.

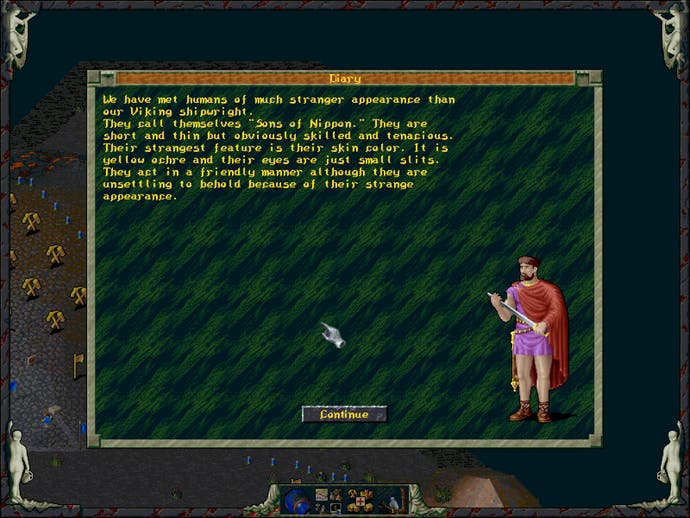

The Settlers 2 is really just one big interconnected system. It's a miniature-yet-sophisticated economy, a lesson in supply management and distribution of goods wrapped around an idyllic island community. And it's a fascinating study in the failings of Sir Thomas More's Utopia. Your village takes on much of the Utopian ideal - everybody does their share of the work for the good of the community, nobody owns anything or demands pay except in kind (miners won't work without food), they all wear clothes of the same colour and style, and there's no conflict at all. Until, that is, you meet another tribe - either natives or settlers marooned from another far-off civilisation.

Then the baser side of human nature comes into force. Tensions rise at the borders between your two peoples. Rather than forging together to create a more prosperous society, you fight. Because history has taught us that architectural and dress preferences are irreconcilable differences. Blue-clad white folks who like Romanesque architecture could never get along with yellow-clad white folks who like Nordic boathouse-style buildings. And neither of them could possibly cooperate with the seemingly strange purple-clad foreigners or the stranger red-clad, dark-skinned natives. Differences sow distrust, and scarcity - be it of resources or territory to expand into - drives all-out war.

You start with hope and optimism and naive faith in the potential of a Utopian society, then fade into greed and fear. What if I run out of resources and my economy crumbles? Who are those strangers with pointy metal sticks? What is this magical gate we're hearing whispers about, and where does it lead to? You chase these questions because your economy - and by extension the security of your village - depends on answers. And that takes you through 10 islands or networks of islands, each of which you purge of minerals and stone and fish and animals on the way to the next. Veni, vidi, vici.

This economic focus got dumbed down in later Settlers releases, which made a point of reducing the need for micromanagement (of road networks in particular) to double down on the military aspects of the game, leaving many fans - myself included - to long for a return to the roots of the series rather than what looks to be more of a clean break in the upcoming Kingdoms of Anteria. The 10th Anniversary Edition back in 2006 showed that the old formula has scarcely aged at all, and that with a lick of fresh paint and a reworked interface it's as good as new, but Blue Byte seems reluctant to once again emphasise economics at the expense of warfare.

We needn't worry, though, as two separate groups of fans have taken on the task themselves. German project Return to the Roots (which requires The Settlers 2 data files) is a kind of Settlers 2.5, with a subtle facelift, speed control, internet and local multiplayer for up to six players, diplomacy, and a new building called a charburner (for producing coal), along with bugfixes, custom rulesets, and enough maps to keep you busy for years. And Widelands looks and plays like a spiritual successor, albeit with much less polish (despite several years of development), that piles on more complexity and variety - more buildings, more materials, more dependencies, and differences between tribes that run more than skin deep.

But in a world where real-time strategy games are big on glitz, glamour, and conflict, I wish there were more efforts to embrace the slow, methodical Utopian critique that exemplified the first two games. We have economics-heavy city building in the Anno series and village simulation in Banished, but nothing with the innocent, optimistic tone (pessimistic underpinnings aside) of The Settlers 2. That, to me, is a terrible shame.