In memory of Call of Duty's cyborgs

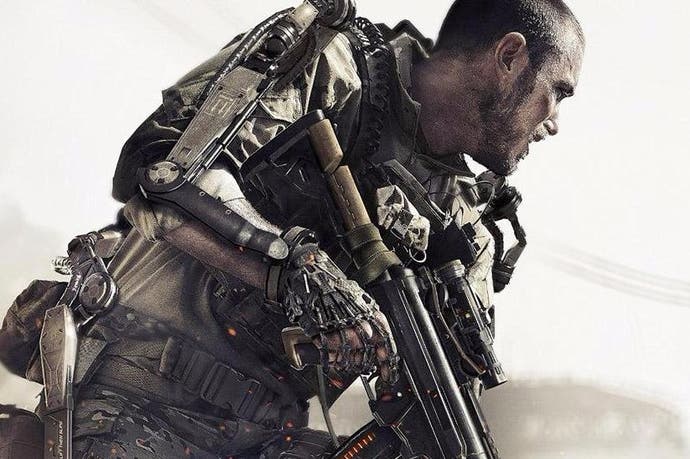

Advancing under fire.

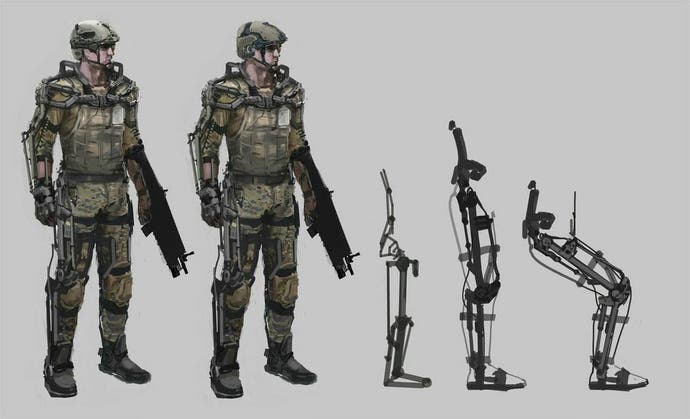

Call of Duty has finally washed its hands of the far future, ejecting from Infinite Warfare's glistening cockpit and plunging headlong into the barbed wire thickets and bullet-churned foxholes of the 1940s. But given that Call of Duty is already the War To End All Wars, reshaping periods and places to fit its own, ageless and perpetually revisited strain of corridor shoot-out, what does a return to World War 2 actually mean in practice? The resumed brownification of video game visuals aside, it means the end of the series' brief, torrid love affair with powered exoskeletons and cybernetic enhancements, initiated by Advanced Warfare in 2014. Exosuits remain the fashion elsewhere - consider BioWare's Anthem, in which mechs surge like dolphins through the foliage of a collapsed Earth - and it's possible that 2018's Call of Duty (Black Ops 4, presumably) will bring them back into play. But Sledgehammer's decision to clear the table of cybernetic enhancements is a pivotal moment for a trope that has given rise to some powerful experiments.

You could argue that exosuits, exoskeletons and cybernetic doodads in general merely elaborate upon tried-and-true mechanics such as double jumps and armour boosts. There's a certain irony to the idea that games like Titanfall and Advanced Warfare are "boundary-pushing", given that each can be viewed as a reversion to the high velocity vertical combat of Quake and Unreal. But exosuits in video games aren't just clusters of character abilities - they can also be a means of distancing you from those abilities, placing them at the disposal of what is effectively a companion character, not quite under your control. Compare Master Chief's craggy MJOLNIR armour to the sinewy Nanosuits of the Crysis games. Halo's developers have conjured up plenty of mystery about the man inside the suit, his "true" face forever threatening to surface, but when you punch out a Wraith tank or line up a Spartan laser in Halo, it doesn't occur to you to wonder whether Chief is his super-soldier exoskeleton or merely operating it. The distinction is, in practical terms, irrelevant.

In Crysis, by contrast, the Nanosuit is very much not the player character, but a kind of fellow creature, a semi-subservient entity with needs and limitations. It has "stamina" reserves that must be painstakingly managed as you flip between stealth, tank tactics or full-blown assault - fail to get the balance right, and the suit will "punish" you, clouding your vision and slowing your motions. Unlike Chief's MJOLNIR kit, the Nanosuit also has a voice, rasping suggestions and warnings at the subcortical level. It's a sinister reworking of the role played by Halo's AI comrade Cortana, who is often plugged directly into the Chief's armour and can thus be treated as an inward extension of his persona, a stereotypical "feminine side", but who never seriously threatens to wrest your control away.

To play Crysis is to be in continual negotiation with this impassive ally, a requirement that thwarts the ostensibly all-important seamless integration of player with avatar. Where Halo famously invites you to see your own visage reflected in Chief's lustrous gold visor - well, providing you're a throaty American man with the emotional range of a cactus - Crysis turns the fact of your disconnection with the game's universe into a source of suspense and intrigue.

This cuts somewhat fascinatingly against how other developers have deployed exoskeletons and cybernetic enhancements to paper over anything in a game that reveals the simulation for a simulation. As the call for greater fidelity in blockbuster shooters has intensified, teams such as Sledgehammer have attempted to transform abstract interface elements into something explicable within the game's fiction - something literally present, an artefact with an in-world history. One of Advanced Warfare's less-investigated quirks was that it sought, by fits and starts, to "rehabilitate" the HUD as an extension of the tech wielded by the player. Ammo readouts appear as holograms sprayed across gun stocks, and there's a ridiculously over-designed all-in-one grenade, its payloads toggled by thumbing the screen on the case. Though a work of sci-fi, Advanced Warfare is also a weirdly convoluted piece of naturalism, one that dances around the thought that you're playing a game by thrusting you into a make-believe apparatus endowed with the same display technology you'd find in a game.

Sledgehammer's series debut both follows on from the brilliant Dead Space, in which every menu is a delightful hologram emitted by Isaac Clarke's vacuum suit, and speaks to how we inglorious denizens of the capitalist west have grown accustomed to cybernetic prosthetics and peripherals in daily life - from actual, commercially available exoskeletons such as the US-made $77,000 ReWalk, to touchscreen watches equipped with performance monitors that look disturbingly like XP wheels. Far from being just a fantasy about bunny-hopping through traffic or hauling security doors apart with your bare hands, this is a game about the UI-ification of perception. Its agenda isn't just to knead machinery into flesh, but to extend the machine's thoughts out into the geography, impressing its logic upon the world.

The script takes a superficial interest in the political and legal implications of this blurring - as the campaign winds down, protagonist Jack Mitchell is forced to reckon with the fact that in becoming a cyborg, he has granted the military-industrial complex power over a part of his body. Mitchell escapes this fate by hacking his own prosthetic arm off - an assertion of the possibility of resurrecting a past uncontaminated by treacherous augmentations. 2015's Call of Duty: Black Ops 3 is rather less optimistic. It portrays a world in which there is no longer a meaningful separation between organic and synthetic perceptions. The game's cranial implants allow you to read environments as though using a level scripting tool - a computerised ebb-and-flow of threat and opportunity, with shimmering polygonal carpets that reveal areas where you'll take more fire - while permitting a rogue AI to infect your character's brain with sorcerous images of crows and ice-locked forests.

Black Ops 3 is a game in which ostensibly pristine categories - "illusion", "reality", "body", "machine" - collapse into one another violently, care of the invasive, destabilising concept of cybernetic technology. Its signature moment: the spectacle of a combat drone tearing your character's arms and legs off, performing the destruction of human autonomy suggested by your reliance on the Nanosuit in the Crysis games. This is an annihilation that travels backward through time to corrupt the World War-set Call of Duties - during one of the game's stranger missions, the Battle of the Bulge level from the very first Call of Duty appears in the sky, folding over you Inception-style as though to physically close the loop between past and present.

It's hard to take a game that promises a return to a simpler, grittier, more "grounded" age of warfare seriously in the wake of such sequences, and I don't get much sense that Sledgehammer will address the implications in Call of Duty: WW2 - an artistic and commercial U-turn seemingly hell-bent on pretending that Call of Duty's sci-fi phase never happened. The possibilities and anxieties roused by Call of Duty's dalliance with cybernetic prosthetics appear to have given up the ghost for the moment, sinking back under the skin.